By 1939 John Sudler Isaacs had achieved notable success in his farming and vegetable canning business, and was continuously buying farmland. What he had not done to this point was to jump on the chicken bandwagon started by Cecile Steele in 1923. He could not help but notice that there was money to be made in raising broiler chickens, and thus took the plunge into that business in the year that the Nazis invaded Poland and set off World War II. The timing of that decision was fortuitous, to say the least; once the U. S. entered the war, a little more than two years later, John S. Isaacs had a buyer for nearly all his broilers in the U. S. military; chickens would make him a millionaire.

Isaacs entered the broiler industry as a grower. Using his own timber, Isaacs built three chicken houses in 1939 near his cannery on Cedar Creek and Isaacs Roads; one of them, at 1,295 feet in length, was thought to be the longest chicken house in the world at that time. However, he lost money on his first flock. In all likelihood, the loss was a necessary and inevitable learning experience; the chicken industry was more complex than what Isaacs and his sons were accustomed to in the vegetable canning business.

LSD Meets NYC

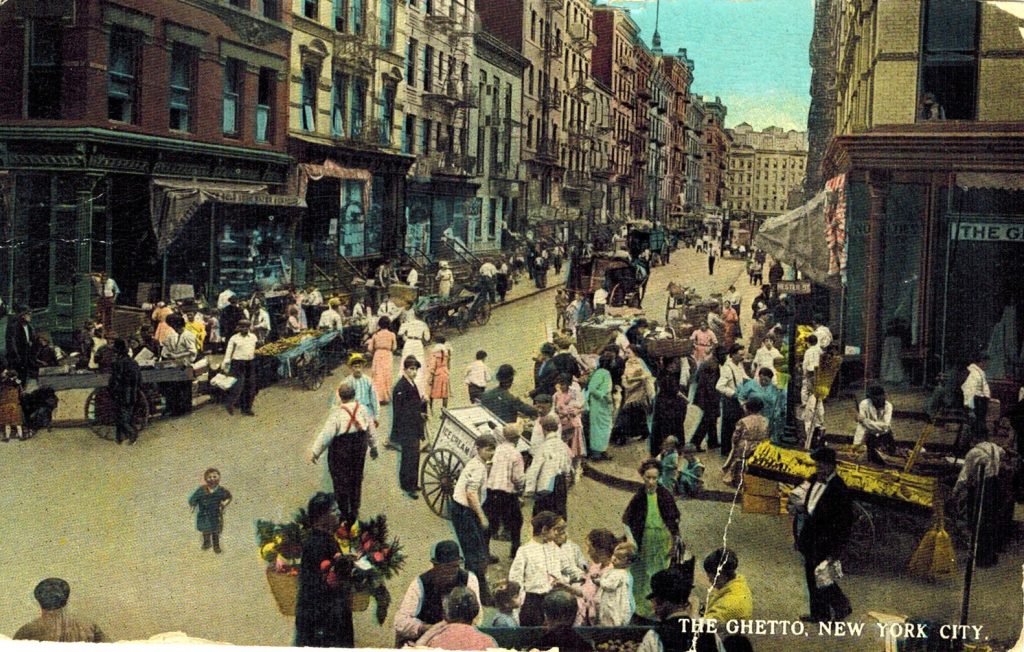

To understand the poultry business Isaacs entered into, we need to understand the market for broilers in 1939. Massive immigration of Eastern European and Russian Jews in the late 19th and early 20th century, primarily to New York City, created a great demand for chicken there. Jews could not eat pork, and beef was expensive; consequently, once broilers were being raised commercially in Delaware, chicken offered an economical alternative as a source of protein. The more entrepreneurial individuals among these immigrants, who knew the city market and their customers, saw great opportunities in the broiler business in Sussex County and the rest of the Peninsula. They came to southern Delaware and other parts of the Peninsula in significant numbers. By 1939 Isaacs and nearly all poultry growers in Sussex County — descendants of British colonists, and many of whom had never had dealings with anyone outside of Delaware — were in business with a very different ethnic culture. Isaacs’ association with one of these New York Jews, Harry Udell, would be instrumental in his ultimate success in this business.

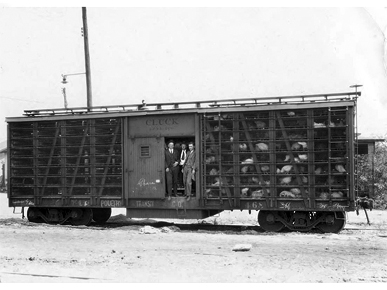

Until the completion of the DuPont Highway around 1934, growers in Delaware delivered live chickens by rail to urban centers, where the birds were processed. Once the north-south highway was completed, live birds were delivered by truck. It was a while, however, before the missing link – local poultry processing plants – would appear in lower Delaware.

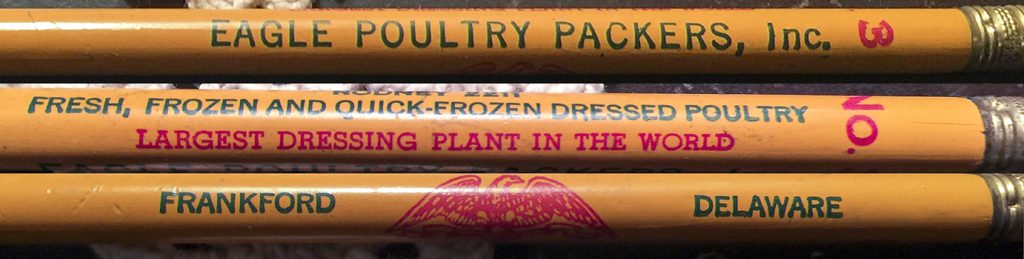

Poultry processors killed and de-feathered the chickens, leaving the heads, feet, and viscera intact, which was referred to as “New York dressed.” Until 1937, all processing was done at point of delivery, i. e. in New York or Philadelphia. That year, the first chicken processing plant in Delaware was started in Selbyville, operated by a subsidiary of the Swift Co. Like many more to follow, the poultry processing plant in Selbyville was a repurposed tomato cannery. Failing to turn a profit, the plant was sold to Sen. John G. Townsend, Jr., who also failed to make a go of it, and finally acquired by Homer Pepper, Helen West, and New Yorker Sam Zahn in 1939. The company was named H & H (acquired by Mountaire in 1977); they were the first successful chicken processor in Delaware, and they were the company that bought Isaacs’ first flock. The only other local chicken processor was Eagle Poultry in Frankford, which began operation in 1938. In 1942, Isaacs would enter into a lucrative business partnership with that company.

The Eagle Poultry Partnership

Within a short time of entering the business as a grower, Isaacs had worked out the poultry processors’ profit margins and was determined to enter the processing side of the business. He started building his own plant in Georgetown in 1941, but jumped at the opportunity to buy a 51 percent share of Eagle Poultry in 1942, raising the capital by selling his unfinished Georgetown plant to the Swift Company. Essentially, he bailed out Eagle Poultry’s owner Harry Udell, who was in serious arrears on taxes owed to the IRS and debts to other creditors. In 1943, Eagle Poultry built a newer, more automated plant and was in a very advantageous position to benefit from the U. S. military’s huge demand for their product.

The effects of WWII on the DelMarVa poultry industry, both good and bad, cannot be overstated. On the plus side, it made millions for the processors, who sold everything they had to the U. S. military. For growers, it was a little less clear-cut. Consider the following facts:

- The U. S. military basically had first crack at 100% of the total production of processed broilers on DelMarVa throughout the war years, and imposed price controls on poultry to keep inflation in check

- Chicken was not rationed for the war effort, but beef was, so that the demand for broilers by consumers escalated rapidly.

- While Delaware growers of broilers were subject to price controls, the feed their birds required was not; consequently, the price of feed rose steadily, squeezing the growers’ profit margins.

The combination of these factors created the conditions for what the Federal Government believed was a massive black market on the Peninsula, primarily involving small independent growers who were difficult for the Federal Government to regulate. At one point, the U. S. Army set up checkpoints throughout Delaware to check the papers of truckers carrying live chickens. Growers were suspected of selling their birds to out-of-state wholesalers who paid prices far in excess of the legal limit mandated by the Office of Price Administration. The situation would not ease up until the end of the war and the end of price controls.

There is an alternative view of the wartime black market in poultry. In 1949 Sen. John Williams of DE announced that he had uncovered evidence that a 1945 report absolving the growers of blame for the black market poultry trade was suppressed. He named a New York racketeer and and cited forged documents provided to truckers that hauled away live chickens for the New York black market; in other words, the small growers were, to a large extent, the victims of fraud. Citing the statute of limitations, the matter was never pursued by the U. S. government.

Meanwhile, there was a chronic labor shortage on the Peninsula, so Isaacs and Eagle Poultry used African Americans, women, and German prisoners of war from Ft. Saulsbury, near Slaughter Beach to fill the gaps.

Isaacs made another strategic move in 1941 in connection with his vegetable business that would prove very valuable to the broiler business as well during the years following the end of WWII. He bought a cold storage plant on Railroad Avenue in Georgetown and transformed it into a multipurpose facility for quick freezing of vegetables, cold storage for meat, and general purpose cold storage rooms available to other businesses such as the grocery chain stores. Frozen foods were a new item in the early 1940’s, and Isaacs was thinking of the future. It was a prescient move; after the end of WWII, poultry prices dropped as the industry suffered from overproduction. Isaacs was able to keep chickens frozen in his Georgetown plant until market prices were more favorable.

John Sudler Isaacs’ foray into the poultry processing business was highly successful, but by 1949, his health was declining and there were concerns about the business practices of his partners in Eagle Poultry. His sons convinced him to sell his share of the firm back to the other principal shareholder, Harry Landes.

Epilogue

John Sudler Isaacs died in October of 1950. After his death, the family continued to maintain nine chicken houses to grow a million birds annually, selling live birds to processors every week of the year. The four incorporated businesses under the John S. Isaacs & Sons name, which comprehended all of the businesses the family members were engaged in, were officially liquidated in 1962, even though they were all solvent and doing well. Issues of health and of other interests competing for the heirs’ attention were factors in the decision to liquidate.

Much as they had been doing since the start of the industry in 1923, growers such as the Isaacs family continued to assume nearly all of the risk, buying chicks from hatcheries and feed from any number of sources, and counting on getting a good price when the time came to sell. This model would last well into the 1960’s, but market forces would bring about changes to drive efficiency and increased profit.

Vertical integration, consolidation and scientific breeding of larger chickens that reached market weight weeks earlier would transform the broiler industry in the 1970’s. The large processors like Mountaire and Perdue provided poultry growers with chickens, feed and services, and the growers supplied the labor and supervision of the flock. The price growers received was preset by contract, which eliminated much of the uncertainty around profit margins. And, unlike the days when chickens were allowed to range outside of their chicken houses during the summer, they now remain inside their house their entire lives until sent for slaughter. Great efficiencies have been achieved, and risk to the growers reduced, but the raising of broilers is now more or less factory farming, an emotional issue for animal rights activists that has been in the public eye for years, but is outside of the scope of this blog post.

Sources

Kee, W. Edwin. John Sudler Isaacs: A Sussex County Visionary. Delaware Heritage Press. 2009.

Williams, William H. Delmarva’s Chicken Industry: 75 Years of Progress. Delmarva Poultry Industry, Inc. 1998.

“Farm Suit Due Referee.” The Morning News [Wilmington, DE], August 30, 1958, Pg. 17

“Intent to Sell.” The News Journal [Wilmington, DE], 27 July, 1949, Pg. 4

“Officials Mum on Poultry Data.” The Morning News [Wilmington, DE], 1 September 1949, Pg. 1

“Broiler Raising Industry Seen Drifting North.” The News Journal [Wilmington DE], 6 March 1939, Pg. 8

Everett, Glen D. “Williams Reveals Details of Wartime Black Market in State.” The Morning News [Wilmington, DE], 30 August 1949, Pg.1

Thanks, Phil! I learned a great deal from this post about several topics, local and national. Nice work! K Kelly