In The Center Ring, From Milton, Delaware, The Most Famous African American You Never Heard Of

Early in March of this year, I received an email through my blog from a retired police officer in the United Kingdom. The writer was Lyn Brown, from Dorset County, on the Channel coast, familiar to U. S. fans of the British television series Broadchurch. Lyn had an ancestor – a great-great grandfather—named Joseph Ledger, whom she believed was born in Milton in 1841, and left at the age of two with his family for Philadelphia, never to return. The fact that Milton-born Joseph Ledger had a British descendant was of more than passing interest to me, but what really grabbed my attention was the fact that Joseph Ledger was an African American expatriate living in Europe starting in 1862, and one of the more famous lion tamers on the European continent in the second half of the nineteenth century. We know from an interview published in the New Zealand Herald on October 4, 1884, something about Joseph Ledger’s physical appearance. The interview took place in Liverpool on the occasion of the last performance of Wombwell’s Menagerie. The interviewer described Ledger as “a rather slim, but well set up African, about 5 feet 11 inches, and if you met him in a train you might think him a shy, retiring man.” He was also a cigar smoker. There is one badly damaged photograph of him as a young man, that depicts an urbane, well-dressed individual.

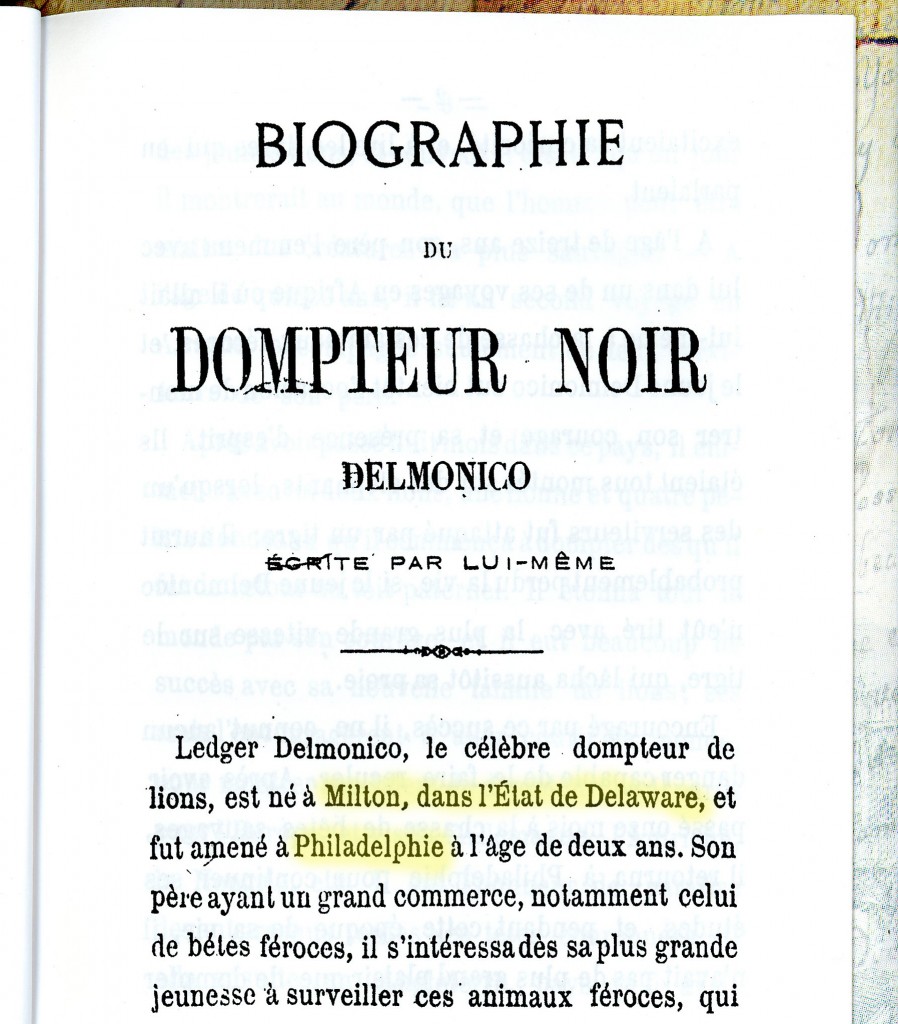

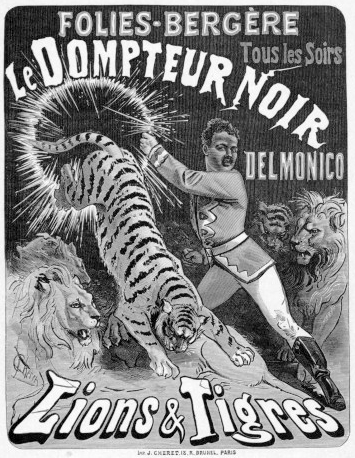

Joseph Ledger’s life as an expatriate is fairly well documented, but his childhood and youth are shrouded in half-truths, dissembling and deceptions. We have only one piece of evidence that he was born in Milton, but it is a significant one: a biography, which he wrote himself using his stage name Ledger Delmonico. Published in Paris, in French, in 1873. It is very short—about the length of an average newspaper article—but it was set in type and printed by Imprimerie V. Fillion et Cie. The very first sentence reads:

Ledger Delmonico, le célèbre dompteur de lions, est né à Milton, dans l’État de Delaware, et fut amené à Philadelphie à l’âge de deux ans. (“Ledger Delmonico, the celebrated lion tamer, was born in Milton, in the state of Delaware, and brought to Philadelphia at the age of two.”)

There is no reason to believe that he would have fabricated a story about his birthplace in a relatively obscure location such as Milton. On the other hand, there is no documentation attesting to his birth in Milton, or anywhere in the United States for that matter; the state of Delaware did not require the registration of births, deaths, and marriages until July 1881. That and the fact that Joseph was African American would have made it unlikely that his birth would have been recorded on anything other than a family Bible. According to family lore, he was born to free parents, but we do not know their names or origins. Having left the county at the age of two means that there are no local school records or church documents in which his name might have been found. A search of the U. S. Census of 1850 turns up neither his name nor that of his parents’ in Philadelphia.

The search in the U. S. is made even more complicated by the possibility that Joseph’s family name started out as Hollinger or some variant of that spelling, and was later changed to Ledger. What name Joseph Ledger was born cannot be conclusively established with the evidence currently available.

His “biography” reads more like self-promotion than a documentary of his life. Written when he was about thirty years old, it does not talk about much else other than his introduction to the taming of wild beasts and the early years of his career. He died in 1901, so the details of the rest of his life have to be gleaned from contemporary newspaper accounts of horrifying attacks on him by wild circus animals, the U. K. Census, and stories passed down by family members over several generations.

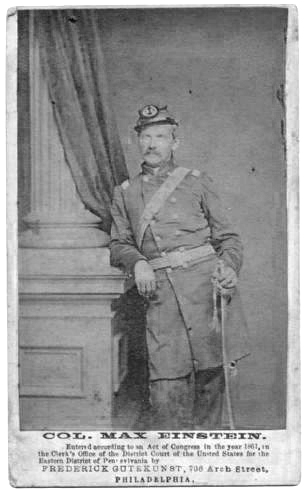

What we know about his childhood and youth is based on family anecdotes compiled by his descendant Lyn Brown. He was supposed to have been educated at “Professor Beard’s School,” of which there is no record. However, various members of the Beard family, who were Quakers and abolitionists, were dedicated to improving the lot of runaway slaves and freedmen who managed to find their way to them, so there is a reasonable probability that he did receive an education from one of the Beards. Another story has him serving in the Union Army in 1861 at the Battle of Bull Run, with the 27th Pennsylvania Volunteers, commanded by Col. Mordecai “Max” Einstein. The Union Army did not enlist African Americans as combat soldiers until after the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, and then only in all-black units commanded by white officers. In all probability, if he served the Union cause it was as a civilian non-combatant, perhaps as an ambulance driver or laborer. Still, he maintained in the interview of October 4, 1884 that he served in the “American War,” and was “the only coloured man in my regiment.”

He writes in his biography that his father was in the business of trading in wild animals—a claim that is difficult to verify—and so Joseph developed a passionate interest in all things relating to the most ferocious of these. He goes on to say that at the age of thirteen, his father took him on his first trip to Africa to hunt for wild beasts, where, mounted on an elephant, he first displayed his skill and courage by saving the life of a porter who was suddenly attacked by a tiger. There are, of course, two problems with this story: tigers are not found in Africa, and African elephants cannot be domesticated for use as transportation. The story would have been a little more plausible if he had said that the hunting trip took place in India.

Joseph goes on to say the first “hunting trip” lasted eleven months, after which Joseph returned to Philadelphia to resume his studies. At the age of fifteen, he went on his next expedition to Africa, a trip that would last eight months, accompanied only by two of his father’s servants. He returned with two male lions, one female, and four cubs, which he went on to train successfully. According to him, this success brought many accolades and he was encouraged to showcase his talents internationally.

What are we to make of these claims? When he wrote his biography in 1873, Joseph Ledger, now using the name “Ledger Delmonico,” was an experienced wild animal tamer and entertainer who would certainly have understood the value of hyperbole in furthering his career ambitions. In the circus world of the 19th century, he would not have been unique in fabricating a persona that was a far cry from the reality of his actual life. That his father was purportedly a dealer in wild animals was probably a fabrication; we are not certain that he knew his father, and there is no record that has turned up of a Ledger dealing in wild animals in Philadelphia. This begs the question: How did Joseph Ledger get his start as an animal trainer?We do know for a fact that Joseph Ledger pursued a career as a lion tamer in Europe; family lore says that he began by training in Germany under the legendary Carl Hagenbeck. The question arises: when did he get to Europe, and how? His name does not appear on any Europe-bound ship’s passenger manifest for any year. The first explanation that comes to mind is that he traveled under an assumed name, or stowed away.

There is another possible explanation, however. Family lore says that Ledger somehow became known to Col. Mordecai “Max” Einstein, the commander of the 27th Pennsylvania Volunteers at the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861. Col. Einstein, a native of Germany who emigrated to the U. S. in 1849 and lived in Philadelphia, was commissioned to command the 27th Pennsylvania at the outset of the Civil War. It was at Bull Run that Joseph Ledger, in the course of his ambulance driving or other duties, is likely to have met Einstein. The colonel was removed from command of the 27th after the battle for questionable, possibly anti-Semitic reasons. He was then appointed Consul-General for Nuremberg, Germany on November 13, 1861 by President Lincoln. The story goes that Joseph Ledger accompanied Col. Einstein to Nuremberg, Germany, as a “bag carrier” or personal assistant, upon the latter’s appointment. The appointment, however, was rejected by the U. S. Senate on March 19, 1862. It is unclear when Col. Einstein actually made the voyage to Germany, and in what capacity; we do know that he returned to the U. S. with his family in May of 1863. On the arriving passengers list at his arrival at New York on May 22, he listed his occupation as “ambassador.” We can draw a couple of tentative conclusions: Col. Einstein did make the trip to Germany with his entire family, possibly in an official capacity, and it is likely that Joseph Ledger accompanied him there – and stayed.

In any event, Joseph Ledger arrived in Germany sometime between 1861 and 1863. Although his descendants believe that he was trained by Carl Hagenbeck, the latter was not a lion tamer. He was a dealer in wild animals, a business handed down to him by his father. Much later in life, Hagenbeck would take up the cause of animal cruelty, and was instrumental in the replacement of the harsh methods by which performing animals were trained with more humane techniques. In his biography Beasts and men, being Carl Hagenbeck’s experiences for half a century among wild animals, published in 1912, Hagenbeck mentions Delmonico (Ledger Delmonico, Joseph’s stage name), not as a student or apprentice, but as a client who purchased three lion cubs and three tiger cubs from him. This meeting took place in the 1870’s, long after Joseph Ledger had established himself as a lion tamer in Europe.

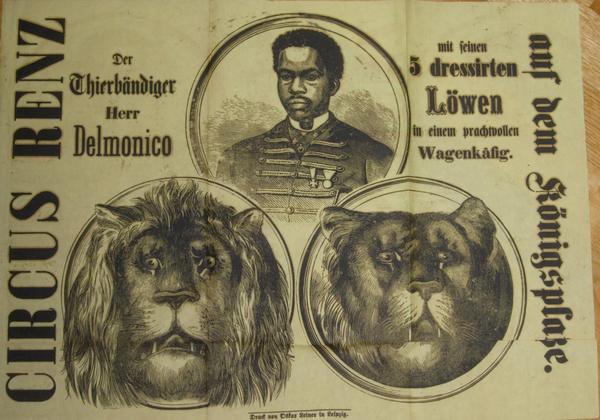

We do know that after his arrival in Germany, Joseph began an association with Gottlieb Kreutzberg, owner of a famous German menagerie. He traveled throughout Europe, including Germany, Austria and Hungary. He traveled and performed with that menagerie, asserting his biography that “he had the honor of performing before nearly all the crowned heads of Europe.” In his October 4, 1884 interview, he contradicts his own biography, stating that he first came to England in 1864, not 1866. We do know that in 1866 he appears to have run off with Anna Wilhelmine Franzisca Kreutzberg, Gottlieb’s daughter, marrying her in Norwich, England early in that year. At this point in time, he is still using the name Joseph Ledger, as that is how he is listed in the Q1 1866 marriage register for Norwich. Joseph and Anna would eventually have four children, three of which survived to adulthood.

According to his biography, his first performance in England was at London’s Crystal Palace in 1866. He joined another traveling menagerie, Edmond Tate Wombwells, and toured with them for six years. During his association with that menagerie, he was injured five times, the last time nearly losing his life. He asserts in his biography that he “retired” from this dangerous career after recovering from his wounds. Based on the time periods he refers to in his writing—a two year hiatus—his retirement began sometime around 1868 or 1869 and lasted until 1871, when he tired of that “monotonous life” and resumed training and performing.

Family lore tells of Ledger serving as an ambulance driver for the French Army during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 – 1871. The name of General McMahon has come up in connection with Joseph Ledger, and that would most likely have been Marechal Patrice Mac Mahon, Duke of Magenta, a senior commander of the French forces during the war, and later one of the commanders who brutally suppressed the rebellion of the Paris Commune. Whether there is any truth to this story cannot be established. Joseph claimed to have received medals in that war and for his Civil War service, none of which anyone in the family has ever seen.

The 1871 U. K. Census lists Joseph by his real name, along with wife Anna and daughter Eva, living in Southampton, and having the occupation of shopkeeper and stationer. For this census, Joseph gave his birthplace as Philadelphia, certain to have been more familiar to the British than Milton, and would continue to do so on official documents. By 1871, it is fairly certain that he is using the stage name of Ledger Delmonico. His listed occupation of “shopkeeper – stationer” fits in with his short “retirement” from performing.

Returning to Prussia (now part of Germany) with his family and five lions he had bought and trained, he began performing with the Cirque de Berq in 1871. He would continue to perform all over Europe, and he mentions performing with seven lions in a cage on March 3, 1872. Kaiser Wilhelm I and family were in the audience for that performance.

With his seven lions, Joseph Ledger (now Ledger Delmonico, or simply Delmonico) performed at the Vienna Exposition of 1873. He asserts he performed before Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria-Hungary; Albert Edward, Prince of Wales; Carl Ludwig-Victor, Grand Duke of Saxe-Altenburg; the prince of Denmark; Prince of Vasa (Sweden); the Prince of Holstein, the Prince of Flanders, and the Duke of Nassau. It was at the Vienna Exposition that he met M. Sari, director of the Folies Bergère in Paris, and was engaged to perform at that venue. It is exactly at this point that the biography ends; whether Joseph intended to add to it in later years, or just got tired with writing, is not known.

At various points during his career, Joseph Ledger trained and performed with lions, tigers, hyenas, and even zebras.

When we get to the 1881 U. K. Census, Anna (born in Prussia), Victor (born in Vienna), and Marguerite (born in Paris) are all listed with the surname Delmonico, and all three include the middle initial “L” in their names. Joseph was in all likelihood on tour somewhere when the census taker came calling. In addition, the family had taken in a boarder with the name of Anthony Delmonico. Whether this is just coincidence or the inspiration for Joseph’s stage name is another matter for speculation.

By the 1891 U. K. Census, Joseph was no longer living with his Anna and his children. Instead, he was a boarder with the Cooksley household in Islington, when not on tour. He gave his occupation as “theatrical profession.” We know for a fact that he was still performing as a lion tamer in 1891; a newspaper report from Liverpool dated November 30th of that year and carried in the New Castle News, New Castle, Pennsylvania on December 2, describes him being “badly torn and bitten” when a lion sprang at him during rehearsal at the Grand Theater. Anna and three of her children were living in Bournemouth, and were using the surname Ledger again. Some of his descendants believe that listing his occupation as “theatrical profession” meant that he had become an actor, but that is not borne out by any evidence. “Theatrical profession” was, for an entertainer like him, a more sophisticated way of referring to his true occupation.

No reports concerning Ledger can be found in the press after December of 1891. Joseph, now in his fifties, may have finally had enough and retired from the world of wild animal training.

What we know of his life after 1873 is contained in newspaper clippings detailing his multiple close calls and injuries, and the interview of October 4, 1884.

He died on July 30, 1901, at Christchurch, Hampshire County, at the age of 59. At the time, he was living with his son Victor, Victor’s wife Emily, and their three young children. His occupation was listed as “actor.” Sadly, the census taker made a notation that Joseph Ledger was an “imbecile – feeble-minded.”