Few stories of Milton people from the distant past have touched me as much as the story of George Washington Atkins II, his wife Lucy and his two daughters. Some time ago, the Milton Historical Society was fortunate to have obtained digital images of the Atkins daughters – Mary Emma Maloy and Estella Hulings, both of whom died at a heartbreakingly young age: Mary at age 20, in 1905, and Estella at age 35 in 1911. For Lucy and George, it was a sore trial to have outlived both their adult children, one that surely broke the spirit of George W. Atkins, who died in 1915 at age 63. Mary was memorialized by her parents on one of the museum windows, when they then-church building was remodeled in 1906.

I’ve been very fortunate recently to have found two digital images of Lucy Mason and George W. Atkins from a publicly accessible family tree, the same one that provided the images of the daughters. Lucy and George are important figures in their own right. Both were stalwart supporters of the Milton Methodist Protestant Church (now the Lydia B. Cannon Museum). Lucy was the daughter of Captain William Stayton Mason, who was better remembered as a land-bound merchant than a sea captain but retained the honorific just the same; he too was memorialized on one of the museum windows, to which Lucy and George probably contributed. Lucy outlived two husbands – George and the Rev. William Mullen Greene; she married Rev. Greene in 1922, who died in 1928. Lucy lived until 1930.

We know a good deal more about George Washington Atkins II. He was the grandson of Captain George Washington Atkins, and the brother of one of Milton’s premier shipbuilders, David H. Atkins. Another brother, Theodore Emery Atkins, was a sea captain who was lost off the coast of Sulawesi, Indonesia in 1885. George’s sister, Margaret Coulter Carey Atkins, would achieve a measure of fame (or notoriety) over her impetuous marriage to Captain John Fletcher Fisher and its aftermath.

George W. Atkins II was destined for neither fame nor notoriety. He and Lucy married at the ages of 22 and 18 respectively, in 1875. On the 1880 census, he gave his occupation as barber, but he did not enjoy success in the tonsorial arts. He found his vocation as a traveling shirt salesman, which kept him on the road “hustling,” as David A. Conner put it in one of his columns. It was no doubt hard work in its own way, traveling by horse and buggy on the poor roads of the time (we have no indication whether George went further afield using railroad transportation). For much of 1895 and 1896, however, he found time to take over writing Conner’s weekly Milton letter, signing each piece as “G. W. A.”

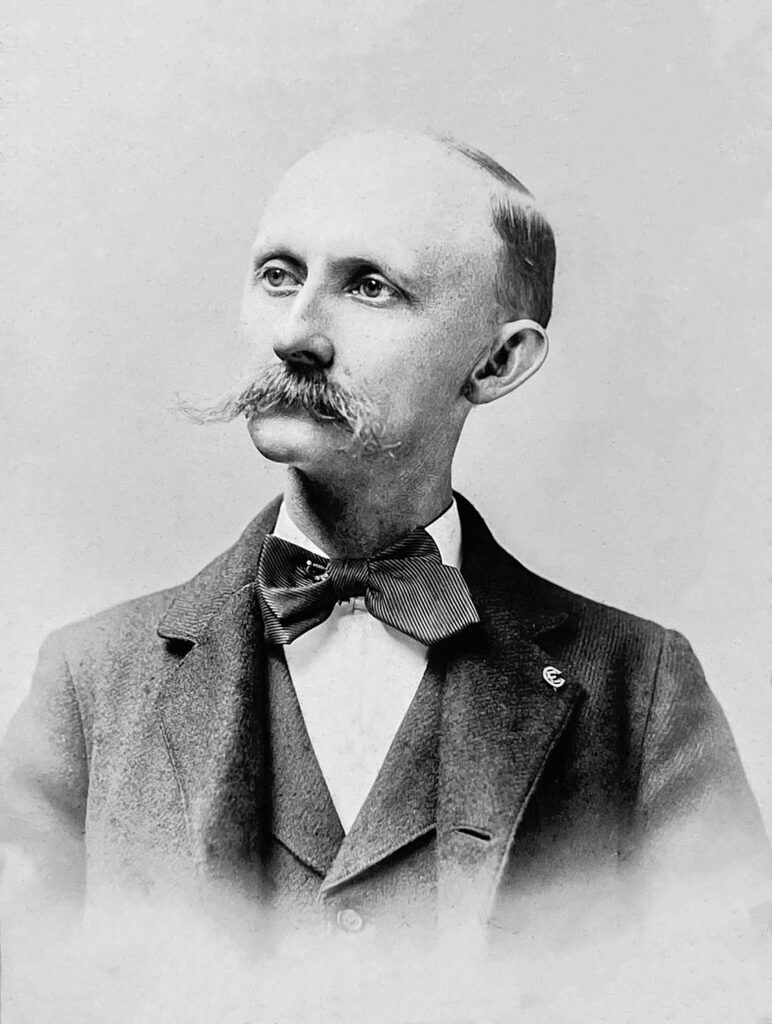

The photograph of George above contains an element that at first baffled me – a pin on the lapel on the right hand side. Enlarged, it shows what appears to be a monogram “E” inside a partial circle, probably a wreath. I looked for lapel pins of fraternal and religious organization of the time and found nothing like it. DeeDee Wood, Executive Director of the Milton Historical Society and an antiques dealer, suggested it might be a Victorian mourning pin, worn by the bereaved for up to two years after the death of a spouse or child. The letter “E” would have indicated someone of importance to the wearer – the deceased. The explanation made perfect sense – the deceased was George’s older daughter Estella Atkins Darby, who died of kidney disease in 1911. This dates the photograph to the period 1911 – 1915, the years between Estella’s death and George’s passing.

George’s obituary, written by David A. Conner for the December 10, 1915 edition of the Milford Chronicle, described him as “a convivial companion, a good conversationalist, and a jovial friend.” He was a member of the International Order of Heptasophs, a fraternal order similar to the Freemasons and Odd Fellows, and very active in the Methodist Protestant church until ill health restricted his involvement.

Thank you! I remember something about a family story about an invention that allowed a passenger to pull down the buggy shades from inside the cabin. One of the brothers left to take it to the manufacturer and they never heard from him again, and the invention came to pass. I will have to look that up as now I am thinking it may have been George Atkins since he spent to much time riding…? I believe it is grandads (Lou Adkins Darby) memoirs.

Sorry I didn’t see this comment sooner – I didn’t get an email notification from the web site like I usually do. This is an interesting story, though; do you have access to your grandfather’s memoirs? There may be a lot in there that can illuminate Milton life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.