Economy, Media, and Transportation

Milton, Delaware in 1906 was as different from Milton of today as today’s Milton is different from Philadelphia or Dover. In 1906, despite the long decline of shipbuilding, Milton was a thriving community of light industry and commerce. Canneries, a brickyard and garment factories provided both seasonal and year-round employment for hundreds of workers. There were grocers, druggists, butcher shops, a bakery, a department store, milliners, no fewer than three barbers, a hotel, a carriage dealer, and a saloon with pool tables. In fact, there was a chronic labor shortage at these factories, especially the canneries, where seasonal workers were often brought in from Baltimore. If not wealthy, Milton’s residents were at least comfortable for the most part and often prosperous.

The town had its own newspaper, the Milton Times, which covered local, national, and international news. The Milford Chronicle offered the same coverage, with the added benefit of a resident correspondent in Milton that sent a weekly letter to the paper about goings-on in town.

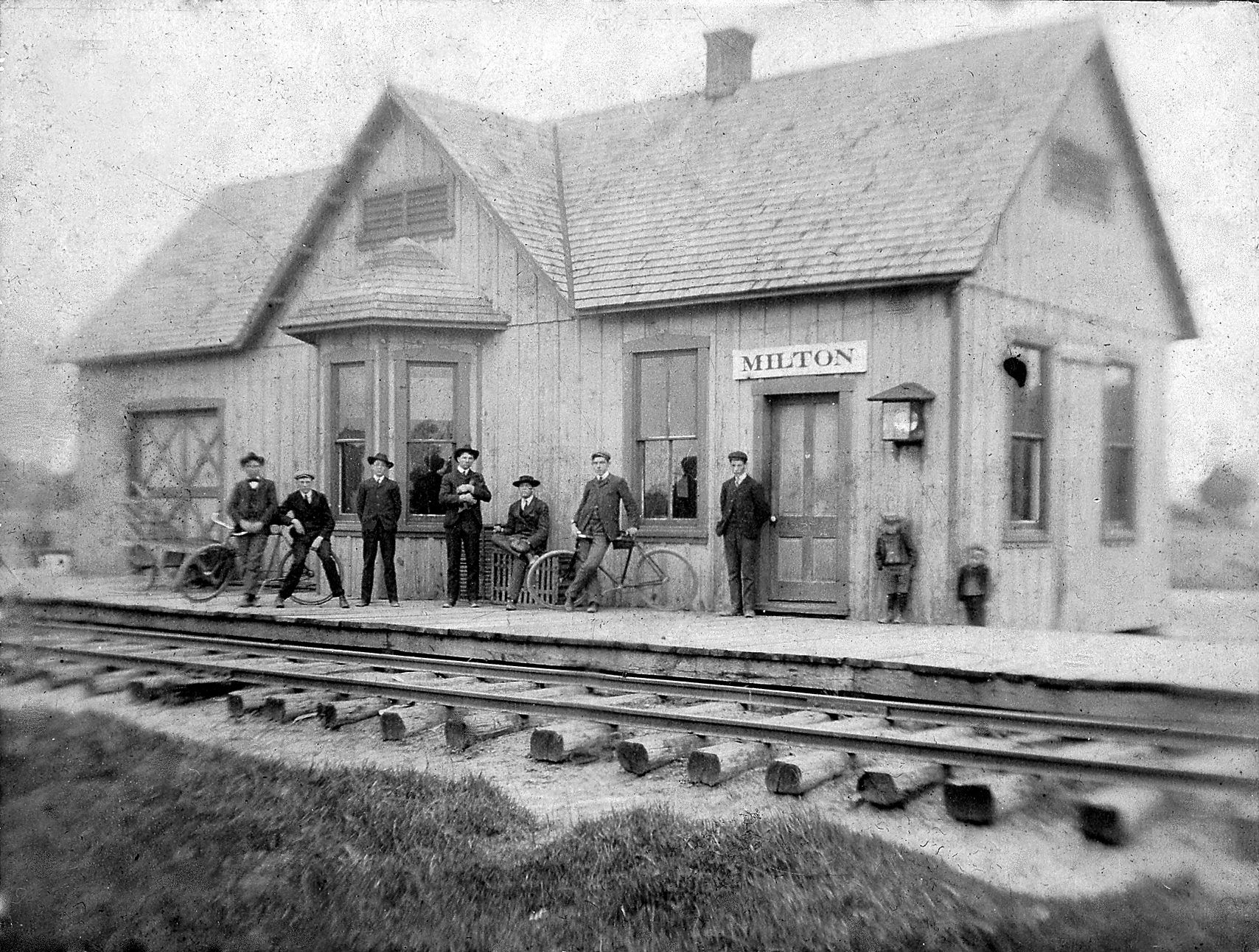

By 1906, residents had seen a few automobiles passing through town, but the primary mode of local transportation was still the horse and carriage for people or horse and wagon for freight. Freight to Philadelphia was still being sent from the Milton dock to Philadelphia on schooners and other small craft. In 1897, the Queen Anne’s Railroad finally reached Milton, running freight and passenger service from Love Point, MD to Lewes, DE; passengers could make connections to points north on the Delaware, Maryland and Virginia Railroad at Ellendale (although scheduling was less than ideal).

Religion and Fraternal Organizations

Religion, primarily the Methodism of the two conferences active on the Delamarva Peninsula, was a major presence in the lives of Milton’s people. Both the Milton Methodist Protestant and Goshen Methodist Episcopal churches in town actively evangelized and sought new members throughout the year. An annual camp meeting (revival) at Lavina’s woods was a social as well as spiritual event. Pastors were admired and respected for passionate sermons which were commented on in the newspapers.

With several fraternal organizations in town – Freemasons, Odd Fellows, Heptasophs, and Improved Order of Red Men, among others – Methodist clergymen often were members of one or more. Fraternal organizations then were as important then as the Chamber of Commerce and the golf course are today for conducting business and forming relationships, and so the clergy were directly involved in the non-spiritual as well as the spiritual life of the town. And, not surprisingly, a minister was always asked to deliver an opening prayer or benediction at high school graduation and other ceremonies, and clergymen often served on school boards.

Perhaps more remarkable to us today is the degree of cooperation among the several churches of Milton in the name of Christian service and fellowship. A notable example was the long-standing practice of “unity services” on Thanksgiving Day, when one church hosted all of the town’s congregations. Ministers from one Methodist conference often preached to the other congregation, and when the Milton M. P. Church was undergoing extensive renovation in 1906 and was thus unusable for several months, the Goshen M. E. Church made their premises available to them for holding services. And, needless to say, all of the churches in town were solid supporters of the Temperance movement.

Education

In 1906, children within the Milton town limits went to school in what was called Milton High School #8, built in 1894, which included primary school grades through high school. Census records show that a primary school education through eighth grade was the most that the majority of children born in the 19th century could aspire to, and indeed many of them did not even reach that level. Attendance in high school was only for the few, and high school graduates were rare. The occupations available to most boys were in the skilled trades, semi-skilled work, or manual labor, none of which required extensive formal schooling. For girls, who were expected to be homemakers, some employment before marriage was available in the garment factories and canneries, and as sales clerks in stores. For the very few that finished high school and went on to higher education, it was often to teachers’ college, after which they might find work in one-room schoolhouses around the county or in larger schools such as Milton High School.

Social Issues

Simply stated, Milton was a man’s world in most respects, as would have been the case most anywhere else in the U. S. at the time. Two women ran their own millinery businesses, and one, Mrs. Sallie Ponder, was part owner of a schooner and other properties which she managed astutely. For most women, church organizations such as the Woman’s Society of Christian Service (WSCS) and lay organizations such as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Movement (WCTU) were the principal means of engagement with each other and the community. The impact of their activities was significant and in keeping with their Christian principles. On the other hand, the idea of universal suffrage was publicly dismissed, and behavior that deviated from idealized Victorian notions of women’s comportment was distinctly frowned upon in the press.

Racism and what we would today call racial profiling were pervasive and jarring to our present-day sensibilities. Nearly all facets of life were segregated, including churches, cemeteries, public schooling and public accommodations, but the worse aspect by far was the immediate presumption of an African-American suspect’s guilt by whites, whether the crime was petty theft or rape and murder. In the most extreme case, the mob lynching of African-American rape-murder suspect George White in Wilmington in 1903 – not by hanging from a tree, but by burning him alive – may have engendered some horror and expressions that “he should at least have been given a trial,” but no challenge to the presumption that he was guilty anyway. These attitudes were as much a part of Milton’s collective thinking as they were anywhere else in the state.

Within Milton, all was not ideal. Young men often gathered downtown at night, shooting craps, getting drunk, swearing, and fighting. For a small town, Milton experienced a surprisingly high number of burglaries of stores and residences in the early 1900’s, as well as chicken theft, vandalism and the occasional stabbing. With one town bailiff and no other police presence, maintenance of public order was of increasing concern by 1906.

Health and Safety

Horse teams remained the primary form of local transportation in southern Delaware well into the second decade on the twentieth century. As a consequence, horse droppings created an unsightly and smelly nuisance. Add to that the fact that people within the town limits still kept hog pens, chickens and other domestic animals, and during the canning season the whole town smelled like tomatoes, and you have a town often filled with unpleasant odors and the potential for disease transmission.

If we could name one fear 1906 that was common to all social classes, races and genders, that would the fear of infectious diseases. In this era before antibiotics and childhood vaccinations, deaths from typhoid fever, diphtheria, pneumonia, septicemia, and tuberculosis struck young and old alike. The incidence of tuberculosis, which was then called “consumption” for its wasting effect on the victim’s body, was astonishingly high for a rural area. Gastrointestinal infections, which are unpleasant but easily treatable today would often kill the patient then; this was especially hard on children under two years of age, whose mortality rate was much higher in lower Delaware than in the rest of the state. Cancer rarely appeared on death certificates; acute infections, degenerative diseases associated with aging, heart disease and stroke were the leading killers of adults.

For children as well as working adults, accidents were commonplace, especially on farms and around large animals. Automobile accidents were as yet unknown in Milton, but injuries due to runaway carriages and wagon teams were routine. Maiming from wood chopping, falls from scaffolding and other workplace accidents were commonplace as well in a community that had very few white collar workers.

Summary

This, then, was Milton in 1906: its babies born at home and its elderly dying in their own beds; people modestly successful in their occupations, seriously God-fearing, engaged with each other and the community through fraternal organizations and church-sponsored groups, aware of the wider world but emphatically dedicated to preserving the social order as they understood it.