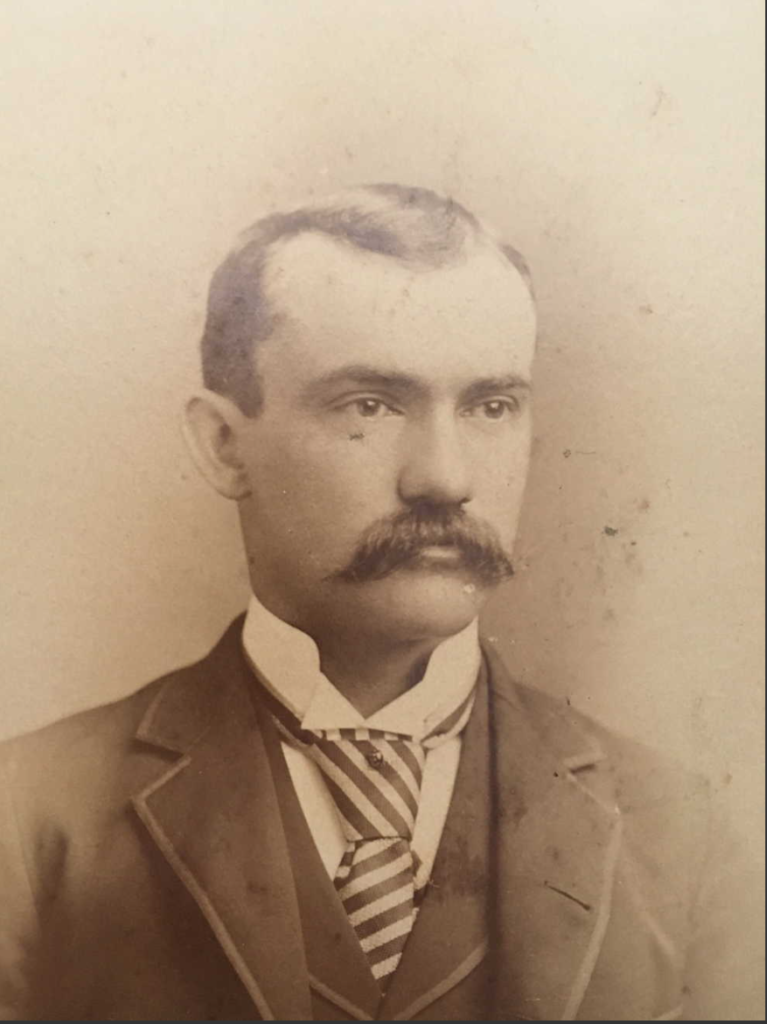

On November 1, 1918, Milton native John Fisher (1892 – 1955), a private in the American Expeditionary Force in France, wrote a letter to his father and mother back home. As with most letters sent from the front lines to family and friends in the U. S. during wartime, his letter is notable both for the details that got past the censors, and those that were left out by him or expunged by the censors.

This post is an attempt to assemble as many details as possible about Private Fisher’s overseas experience. The principal source is his letter, from which several portions are excerpted, but there are other sources that fill in many of the gaps.

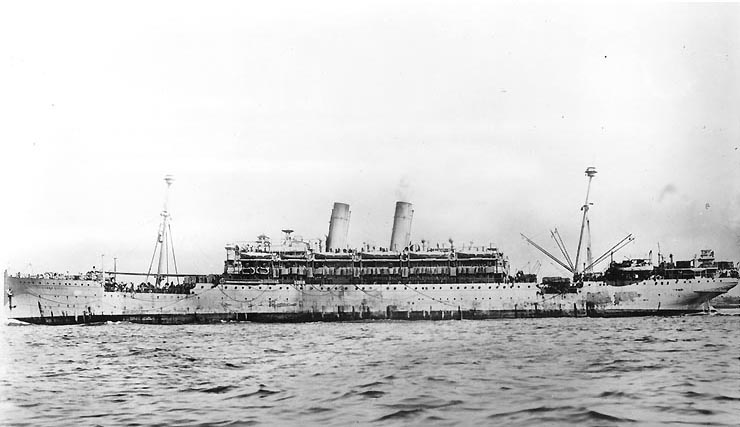

To begin with, John Fisher was an enlisted man in the 29th Division, 57th Infantry Brigade, 113th Infantry Regiment, Company I. This is all documented in the passenger manifest of the troop ship his unit shipped out on, the USS Princess Matoika. The 29th was first constituted as a U. S. National Guard division in July of 1917, three months after the U. S. entry into WWI. Consisting of men from former Confederate states as well as states that remained in the Union, the 29th became known informally as the “Blue and Gray” division. Reorganized in 1939, it would eventually participate in the D-Day invasion – “Operation Overlord.”

In the first paragraph of his letter, Private Fisher alludes to his unit’s activities upon arrival at the front sometime after September 26th, 1918:

My dear Father and Mother,

Well, this finds me alive, well and happy and with a whole skin. We are now away back from the front lines at a rest camp and I don’t think we will ever see any more fighting, but don’t forget that we have been in it and have accomplished and succeeded in the greatest drive and one of the hardest battles the world has ever known. In one way I am sorry to say that I did not get to go over the top with the boys as I did not get back from I. M. detail in time, but went to the reserve line to join them and spent about a week with then in what is known as “Death Valley,” and don’t let anyone kid you when they speak of that great valley by that name, for the one who have it a name gave it an appropriate one and he didn’t have to study long, for there was sure some heavy artillery there….

In fact the 29th Division was part of the massive Meuse-Argonne offensive, which involved troops from all of the Allied nations along the entire Western front, and lasted from September 26 to November 11 – Armistice Day. About 1.2 million American soldiers took part in what Private Fisher describe as “the greatest drive and one of the hardest battles the world has ever known,” making it the largest single offensive in U. S. military history, as well as one of the deadliest. 26,277 doughboys were killed, and many more wounded. Private Fisher’s division experienced 30% casualties – more than 5,800 officers and enlisted men killed or wounded. Successful (and brutal) as it was, the American involvement in the Meuse-Argonne offensive was dwarfed by British and French battles with the Germans earlier in the war, on the Somme and at Verdun, for example, which involved many millions of troops and appallingly huge casualties on both sides.

As for the location of “Death Valley,” several locations received that moniker throughout the war. The one that Private Fisher refers to is probably near Bois Belleau (Belleau Wood) on the Meuse.

It appears that Fisher did not participate in the initial, and deadliest, phase of the offensive, having been assigned to the rear and joining the reserve line about a week before he wrote his letter. He did experience German shelling, referring to the slang names for enemy ordnance and the sounds they made:

The shells came over in all sizes and descriptions and the boys nicknamed the different kinds and sizes of shells as “Rolling Kitchens,” “G. I. Cans,” “Whiz-bangs,” etc. The Rolling Kitchens were told by the sound. They were extremely large, long range shells with high explosive and shrapnel. A fellow could hear them coming and have some time to duck. They sure were no joke. The G. I. Cans were about the same, only smaller and not so long range generally, but when exploding, sounds like hundreds of tin cans falling from a runaway wagon on the stone pavement. The Whiz-bangs were smaller shells used on the front lines and were extremely speedy and used at short range.

A rolling kitchen was just that – a small, mobile kitchen that could be brought out to troops on the front lines to serve hot meals. Apparently, the shells with that nickname seemed to be of that large a size. They moved at subsonic velocity, and could thus be heard coming. G. I. cans were galvanized garbage cans, and the nickname was due to the noise the shells so named made on exploding. The whiz-bangs, smaller in size, moved at hypersonic speeds and could not be heard until they were very close (the “whiz”) followed by the “bang” of the explosion.

Private Fisher had more to say about trench life, although he probably did not spend a great deal of time there:

Well, mother, here is a funny one. I can see you shudder as you read it but we take it as a joke, for we are all alike, from the high officers down to the privates, when we came out of the lines we were as lousy as any dog ever dared to be. I saw one fellow’s shirt that almost looked as if it were set in diamonds when the light shone one their backs. I only found two on me but I know of no reason why as I did not have a change of underwear for over five weeks. I got a hot bath yesterday and all new clothes so I feel much better. They were the black back kind so we called them German lice on account of the black insignia on their backs. We got them from the dugouts that once belonged to the Germans; in fact, Germans occupied them only a few days previous. I have a lot of interesting things to tell you but I will have to cut it short as I am afraid you will get tired of reading such stuff.

A lot of interesting things indeed! By one estimate, 97% of soldiers who spent time in trenches were plagued by body lice. Aside from the itchy discomfort and, for some, misery they caused, these insects could spread a non-fatal but debilitating disease called trench fever, which could put a soldier out of action for months. The trenches were also overrun with rats, who fed on waste and corpses found both outside and inside the trenches. During rainy weather, trenches would fill with water and soldiers could contract trench foot, which caused their feet to swell and decay. Add to that the horrifying shelling and sniper fire, and it is surprising that more men didn’t lose their sanity on the front line. It’s probably a very good thing that Fisher cut off his narrative before moving beyond lice.

He had the notion when he wrote his letter that he would be home very soon:

I will tell you more some time when I get home, which I don’t think will be very long now as Austria has already given up.

Private Fisher remained in France for some time after the Armistice was declared. He boarded the U. S. S. Floridian at St. Nazaire, France on May 4, 1919, and arrived at Hoboken, NJ on May 17. He returned to Milton in early June.

Upon his return, John Fisher worked with his father Charles and brother Alvin in the C. W. Fisher & Sons store in Milton.

On November 10, 1933 the Milford Chronicle reported that Fisher would address the Greenwood Grange meeting on November 13 to tell stories of his experiences on the front line in WWI. He was certainly a good storyteller, as his letter shows, and he probably told those stories many times to many audiences. Throughout his post-war life, he was active in fraternal orders such as the Masons and the Odd Fellows, in the American Legion, the Milton Lions Club, the Milton Businessmen’s Association, and in various charities.

Fishers’ letter to his parents, from which the excerpts in the post were obtained, was printed in its entirety in the Milford Chronicle edition of December 20, 1918. A link to the newspaper page, courtesy of the Library of Congress and the University of Delaware, is provided below.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/29th_Infantry_Division_(United_States)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meuse%E2%80%93Argonne_offensive

Milford Chronicle, November 10, 1933 and November 18, 1955