The “Sunday School” window was presented by the girls’ Sunday school class taught by Frances (“Fannie”) Hopkins Leonard (1880 – 1947), the daughter of Civil War veteran James P. Leonard (1845 – 1934) and Eliza Clifton (1847 – 1936), who were married in 1870.[1] In the Federal census of 1880, the name recorded for Frances Leonard at birth is Mary F. (presumably Frances) Leonard, but she never used the name Mary in any other document.

Fannie, as she was known to her friends and family, was a member of the Milton chapter of Daughters of America, and was active in the Milton M. P. Church. She served as a delegate to the Methodist Protestant Sunday School Convention in 1901, was elected treasurer of the Milton M. P. Sunday school organization in 1902, taught a Sunday school class for several years, and was a delegate to the Sussex County Bible Society on at least one occasion.

The Milton Historical Society has an album full of postcards collected by Fannie Leonard from 1903 to 1910, most of them addressed to her, but a few written by her. There are a number of other postcards written by her to Eliza Robbins of Ellendale during the same time period. These postcards, the only personal papers of anyone connected to the stained glass windows of the Milton M. P. Church, offer a glimpse into the personal life of a young woman in her twenties with at least three young men interested in her romantically. One of them is Otis D. Joseph (1882 – 1942) of Hollyville; she seems to have had mixed feelings about him, and nothing came of the relationship. Another suitor signed his cards as “Will,” and yet another as “The Kid.” These two may be the same person, but that is only a guess. We do know that “The Kid” served in the Delaware National Guard and spent time in a training camp in Pennsylvania. As with Otis Joseph, nothing came of this relationship.

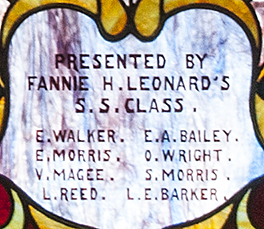

If any year in Fannie’s life could be identified as a zenith, that would be 1906, when she and seven of her Sunday school students staged a performance of the three-act farce The Oxford Affair to raise money for the remodeling of the M. P. Church building. That fundraising earned them a place on one of the stained glass windows. David Conner describes Fannie as having a “queenly bearing” in his (probably highly biased) rave review of the performance.

A store clerk in 1910[2], she married Arthur M. Barnes (1887 – 1929) of Lewes on January 17, 1912 as noted in the Milford Chronicle of January 26. The ceremony was performed by Rev. George McReady, and the newlyweds went to Philadelphia for a brief honeymoon before returning the following Monday, where a reception was held for them at her parents’ home. They took up residence in Lewes.

We first hear of Arthur in the March 31, 1911 edition of the Milton Chronicle, where he was reported to have spent a day-and-a-half in Milton. It is not known whether he and Fannie became acquainted on that first visit. In July of 1915, Arthur is appointed the special Saturday night policeman for Milton, owing to his large physical stature. Arthur’s WWI draft registration describes him as a tall, stout, blue-eyed farmer with two fingers missing at the first joint. He would later give up farming and, among other occupations, serve as police chief of Newark, DE.

The October 17, 1919 edition of the Milford Chronicle, under the “Sussex County Court” heading on page 1, reports that the case of State vs, Arthur Barnes for wife-beating was continued until the next court term. This is the first indication we have that the marriage was troubled. By the 1920 census Frances and Arthur were still married, but she was living with her parents in Milton and he was living with his in Lewes. The Milford Chronicle of February 28, 1919 states that Frances had been “seriously ill since last September, suffering from internal injuries followed by a nervous breakdown.” Later that year, in November, Frances underwent surgery in a Philadelphia hospital; she was accompanied by William G. Fearing and returned to the home of her parents, where she remained bedridden for months. The next time we hear about her is in the Milford Chronicle June 18, 1926 edition, when it was reported that she and about 100 other Milton women were the victims of a door-to-door hosiery salesman’s scam[3]. In the December 31 edition of that year, it is noted that she received visitors from Philadelphia and Atlantic City. Illness, however, dogged her; in November of 1929 she was again reported to have been hospitalized, just a few weeks after Arthur’s death. Her name appears once more in the September 18, 1936 issue with the information that she is returning home after managing the Treasure Chest Shoppe in Rehoboth Beach for two months, so we know that she sought employment outside her home at least once.

City directories for Wilmington show Arthur living there in 1921 and 1923, his occupation that of policeman. This is corroborated by the newspaper article about his shooting death. Arthur’s 1929 death certificate indicates that he is divorced, which would place the date of divorce sometime between 1920 and 1929. He died of an accidental gunshot wound in Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was working as a foreman in a Ford auto plant. The shooting story made the front page of the Delaware County Daily Times issue of September 16, 1929.

Frances Leonard’s marriage to Arthur Barnes is highly atypical for the time, in that Arthur was much younger than Frances and the marriage itself ended in divorce. She never remarried. In October of 1947, a few weeks after her death in Beebe Hospital from a heart ailment, all of her personal property, which included antique glassware, furniture, dishes, and other goods was auctioned off at an estate sale that attracted “antique buyers and faddists from all parts of the state.” Bidding was “spirited” and selling prices were high.

———————————————-

[1] A volunteer, James P. Leonard served in Company H, 3rd Delaware Infantry Regiment, maintaining the rank of private through the end of the war, and saw action at the battles of Antietam, Cold Harbor, and Petersburg, among others. His pension was raised to $30 a month by Congress in 1916.

[2] The July 28, 1905 edition of the Milford Chronicle reports that she worked at the C. H. Atkins Store in Milton, where she suffered an attack of “neuralgia of the heart” from which she recovered.

[3] A few weeks later, the under-aged perpetrator was found in Orange, VA and went before the juvenile court judge; all of the Milton victims of the scam were paid restitution by one of the culprit’s relatives