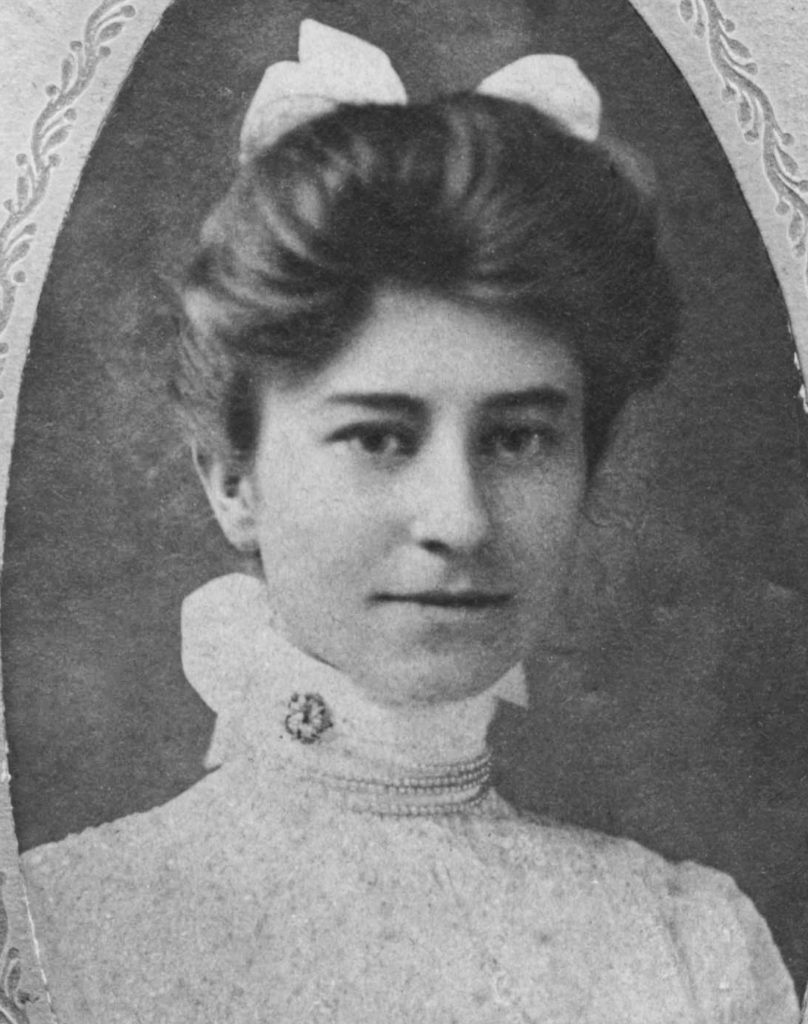

The window at left, on the North Wall of the LBC Museum, was presented in memory of Mary Emma Maloy Atkins (1885 – 1905) by her parents, George W. Atkins (1852 – 1915), a shirt salesman and prominent Milton businessman[1], and his wife Lucy A. Mason (1855 – 1930). Her middle names were given in honor of Emma Malloy, daughter of the Rev. J. Earle Malloy, pastor of the Milton M. P. church from 1884 to 1886. Mary was by far the youngest person for whom a window is dedicated in the Milton M. P. Church. She died suddenly in 1905 at the age of 19. Her terse epitaph – “God took her” – barely hints at the grief her untimely death caused her family. In short eulogy in the Milford Chronicle, the writer begins with a quote from a now-obscure poem by the British poet Felicia Dorothea Browne Hemans (1794-1835), “The Hour of Death,”[2] then states “Perhaps no death has struck such consternation in the hearts of the people of Milton as that of Mary Emma Malloy Atkins.” The writer describes Mary as “…one of the fairest flowers that Milton ever produced.” After a day of skating and sleigh riding she went home, then fell into convulsions and unconsciousness from which she never emerged. At the end of the eulogy is a quote from another poem, Rest, by Mary Torrans Lathrap (1839 – 1895).[4]

Death was a constant presence in Sussex County in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Milford Chronicle reported the death in Milton of an infant or child under the age of 5 nearly every other week, and the threat of infectious diseases such as typhoid fever, cholera, tuberculosis, pneumonia, scarlet fever and dysentery was always present. Drowning and accidents, work-related or otherwise, were all too common and a leading cause of death or serious injury among children. One can infer from Mary’s eulogy, however, that the inexplicable death of a healthy young woman in her prime was simply more than one could bear.

David A. Conner was quite likely to have been a friend of the Atkins family; he reported George’s business trips every time he made one and made sure to praise him as a real go-getter. In at least two articles he calls Mary Atkins by her nickname “May.”

The complete text of Conner’s printed eulogy to Mary E. M. Atkins can be found by clicking here.

——————————

[1] Nicknamed “the hustler” in the Milton Chronicle, George W. Atkins ranged up and down the Delmarva Peninsula looking for wholesale buyers of the shirts produced by the Douglass and White Shirt Factory.

[2] While obscure to us today, in Victorian times the poems of Felicia Hemans were used as instructional material to teach moral and spiritual values to children. Felicia Hemans enjoyed a measure of literary success in her lifetime and was still being read in schools in the U.S. up to the mid-20th century. Her work would have been as familiar to any educated person in 1905 as the Robert Frost poem “Stopping by the Woods on a Snowy Evening” would be to his counterpart today. The Milton columnist quotes twice from “The Hour of Death,” and closes with a quotation from Mary Torrans Lathrap. David Conner quotes from The Hour of Death on numerous occasions throughout his journalistic career, as well as from dozens of other now-obscure poems of his time.

[3] D.A.C. were the initials of David A. Conner (1843 – 1919), a decades-long resident of Milton and the town’s correspondent for the Milford Chronicle. His sometime florid prose, philosophical ruminations, and romantic sensibilities reflect the Victorian mindset of his time.

[4] Mary T. Lathrap, an evangelist and temperance activist, is still widely quoted today in inspirational books and messages. A Michigan native, she was a lay preacher in the Methodist Episcopal Church and was elected president of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union in 1881.