I’m often asked what motivates me to write about Milton, a place I’ve only recently arrived at, relatively speaking, and where I have no family roots. I think I’m now ready to explain myself more fully, so this will be a personal essay, rather than one about the usual topics I post about.

On a recent trip to Turkey and Greece, my first trip to either country, I came face to face with my roots. This sojourn of two weeks had a marvelously unsettling impact on me, one that I am still processing. Since most of my readers don’t know much about me, I’ll have to divulge a little of my life story in order for any of this essay to make sense.

Born in the U. S., I was the child of immigrant parents, refugees from the chaos of post-WWII Europe. They were both members of an ethnic Greek minority in southern Albania, in a region where you are what your language and religion say you are, not necessarily what the geography of your birthplace dictates. My father was born just two years after Albania broke free of the Ottoman Empire, and my mother a few years after that. For their entire lives, however, their birthplace was just an inconvenient truth; all that mattered was their steadfast, passionate identification with the country that lay about 50 kilometers to the south of their ancestral villages: Greece. Assimilation in Albanian society for them, despite the advantages it might have offered, was more than undesirable. It was anathema.

My mother grew to adulthood in the village she was born in, and rarely encountered people from outside her ethnic enclave. The isolation ended her schooling after six years; she would have to go to an Albanian-language boarding school to advance further. She told me once that she had though of becoming a teacher, but that was not going to happen. My father, on the other hand, was sent away after finishing primary school, to live with relatives in Greece and further his education there. He would spend his formative years in Corfu and Athens, not in his home village. He made it through high school and normal school (teacher’s college), and taught the primary grades for a time.

World War II and the civil war that followed would upend my father’s life; there was no future for him in a war-ravaged, impoverished country. There was no going back to Albania, either, even if he wanted to; the Iron Curtain had sealed that country’s borders and would keep them that way until the end of Communism in 1991. He made the decision to emigrate.

My mother’s family also made the decision to leave, and that involved putting their lives in the hands of a smuggler to cross the border to Greece. With family members ready to receive both my parents, they crossed the Atlantic in separate voyages in 1948, not aware of each other’s existence until after being introduced a year later by mutual acquaintances. After a short engagement, they were married in 1949.

Barely aware of what they might find in America, and overwhelmed by the pluralistic society they encountered once they arrived, they clung fiercely to every aspect of their origins. As many immigrants have always done, they settled in a community of others like themselves, in New York City. They went regularly to one of the many Orthodox churches already established there, and their circle of friends was comprised exclusively of Greek immigrants, some from their home villages in Albania, and others from Greece proper. English was never spoken at home.

When I was born, I was immediately sequestered in a linguistic, cultural and religious bubble which would last until I went to school. Somewhat subversively, I learned to speak English from Looney Tunes characters, which I watched on the Philco television my father bought when I was about three years old; I was fluent before kindergarten. When a Greek parochial school was started in our community, I was one of the first students enrolled. That was when I began to realize how very small my world was.

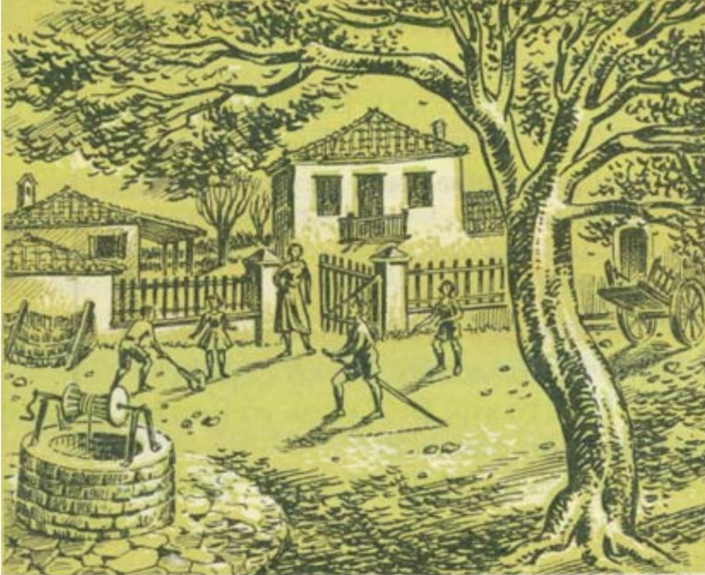

The school day was divided between two very different academic spheres. In the morning, we learned our three R’s in English, reading from textbooks that recounted the adventures of the famous Dick and Jane who roamed their sunny, leafy suburban streets on trikes and bikes, and lived in single-family homes with grassy yards and white picket fences. In the afternoon, we learned to read our parents’ language from a 1955 primer with its own version of Dick, Jane, and Sally: Mimi (a boy), Anna, and Lola, all three about the same age as their American counterparts. These children lived in a small village in a multigenerational household, kept chickens, walked past wheat fields and orchards to go to school and church, cooked on wood stoves, and took short trips to the seashore. If not for the language, the setting could easily have been Milton in 1955. At 9:00 AM every school day, we pledged allegiance to the flag and to the republic for which it stands, then recited the Lord’s Prayer in New Testament Greek; both of these recitations were mechanical, if the truth be told.

Note: I cannot post an illustration from any of the Dick and Jane readers, as they are all still under copyright protection.

For me, there was a growing tension between the morning and afternoon worlds at school, with both seemingly disconnected from my everyday experience. We lived in a crowded apartment building in New York, and my parents’ ancestral homes were beyond reach behind the Iron Curtain. I wouldn’t get to visit a real farm with olive trees until I was in my thirties. Of course there was safety and security within the bubble, but for me it came at the price of an inexorable disengagement from home, school, church, and the idealized world of Dick and Jane as well.

Fast forward to the aftermath of the social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, when I found myself adrift. My peers and I sought to tune in, turn on, and drop out. Ultimately, that didn’t work for me. Instead, I sought assimilation – whatever that meant, whatever the cost. I latched onto a corporate career and a secure and safe life in a bland bedroom suburb. My son and daughter would lead a Dick and Jane life, and they were the primary reason I was able to achieve a kind of reconciliation with my parents. Beyond my role as husband, father, and provider, the question of who I really was remained unanswered for most of my adult life.

You may now wonder, “What, if anything, does this back story have to do with Milton?”

When my wife and I were scouting locations for our retirement, and visited Milton for the first time in 2010, I was immediately and strongly attracted to the town. Walking along Federal Street in the Historic District, I felt I had stepped out of a time machine into the 19th century (if I ignored the cars zipping down the street). And, while New York City had plenty of historic neighborhoods from that era, Milton had a small-town, human scale to it that made it drew in an outsider. It was a purely emotional reaction to the place, one that I have heard other transplants say they’ve experienced on their first visit.

The real revelation would come a few years later, in 2014, after we had built a house just outside the town limits and settled in as retirees. It was in that year that I visited the Lydia B. Cannon Museum on Union Street and began researching and writing about the people who have lived in Milton through its two centuries of boom, bust, and reinvention. I discovered a calling: some have dubbed me a “historian,” but I am more of a storyteller, albeit with standards I try to maintain. I have looked at the town throughout its history, often through the eyes of its inhabitants who left written anecdotes about it. The life stories of some long-dead Miltonians became more familiar to me than those of my own relatives.

Something was still missing, and it would take this year’s trip to the eastern Mediterranean to finally open my eyes to what it was. Having been steeped in the history, language and religion of the region throughout my childhood, it was quite emotional when I stepped into that world for the first time. Unlike what you experience living in an immigrant community in New York City, there was no competing imperative of pluralism and assimilation in Athens or Rhodes; the signage in restaurants, hotels, and highways were all in Greek; the people (other than tourists) spoke the language I grew up with, were genuinely interested in my family origins, and beamed with pleasure when responded to their inquiries. It felt like “home,” even if my real childhood home was contentious and often dour.

Then there was the history – thousands of years of it, everywhere. The opulence of Istanbul’s mosques, the nine cities layered over the site of Troy, the broken grandeur of the Acropolis in Athens: I reveled in all of it. I am sure I trod the same ground as my mother and father did in Piraeus, where we arrived at the end of our cruise and where they left for America 75 years earlier.

My identity is inextricably bound to my parents and their forebears, their language, culture and Orthodox faith. There is no reason to run away from it now, but to embrace it. The urge to write about Milton’s history – or tell stories, if you prefer – is rooted in the upbringing and education that exposed me to thousands of years of mythology, war, and civilization, much of it imparted to me by teachers who were storytellers at heart. History was a living, breathing thing for me as a child. And, perhaps, at some level, I felt something in Milton and its surroundings that reminded me of the rural Greek stories I absorbed as an early reader. But, where that history was a palpable presence in my daily life, I had the strong sense that much about Milton’s past was hidden and in danger of being forgotten in a generation or two. That is why I write – so Milton’s own stories do not slowly disappear or lose relevance.

Let the academics study the ancient world of Greece and eastern Mediterranean; I’ve left my heart there, but I’ve found my niche right here on the Broadkill.

Beautifully well written! Thank you for sharing! This helps us Miltonians who were born and raised in the town understand the insurgence and growth of our once small quaint city. It almost make me want to value it more than I used as a child growing up who only wanted to leave it and move to a bigger and popular place. You helped me see that indeed we have something extra special to offer the world!

It’s often the case that we don’t see the value of where we happen to be until we’re no longer able to be there, or the place is gone. Thanks for your interest in the blog!

Beautifully written piece of history and how the past shapes our future. We love our little town of Milton. It reminds me of Ireland!

Yes, Ireland and countless other small towns and villages throughout the world. They don’t have to look alike, nor does the language of its people have to be English, but the feeling of being part of a small community is very much the same. Thanks for your interest!

This is such a wonderful story of your life. You really did find yourself. PD felt that way in Switzerland . He met family and we all became family and to this day we talk and visit when we can. Thanks for sharing this.

I knew you and PD would relate to this. Thanks for continuing to follow the blog!

We are all fortunate you chose to make Milton your adopted home. ευχαριστώ!

Παρακαλώ, Bill! Always glad to hear from a descendant of the seafaring Conwells!

While our backgrounds may be different I am very moved by your story and what motivates you to write the almost forgotten stories of Milton DE. As a grand child of immigrants (Italy), and city dwellers of Italian enclave of S. Phila. I was born in late 50’s, and the impact of TV and the rapidly changing world had a similar impact on me, I understand the disconnected sense of experience of “living in two worlds”. This sense of living in two worlds became more hightened when my parents moved from S. Phila

to suburban New Jersey and the world became larger for me. Many years later when I traveled to Italy (Rome and Florence) in the ’90s I felt an overwhelming feeling of “coming home”. Actually it started when I boarded the flight on Alitalia and the boarding crew pronounced my name correctly for the first time in my life other that my parents and grandparents! When I landed in Rome the phone book in the hotel room had several pages of listings of both my paternal and maternal surnames, Morace and Mirra although my grand parents were from Sicily and Naples. Similarly I felt very connected to this little town and immediate fell for its charms. I enjoy reading your stories and understanding the context of time and place and I am very glad that you write them! To me history is a living thing and “the past is always present”.

Rosemarie, thank you so much for your response; only a person caught between two worlds could understand what it feels like! The great thing is, we can eventually embrace the two worlds, if we want to.

Thank you for your wonderful story! And thanks for your delving into Milton’s history. Milton is very lucky that you happened upon the small town. Keep up the good work. Thanks.

It is a pleasure to hear your kind words, Ellen!

Thank you so much for sharing!

I was born and grew up at 612 Federal Street, Milton. Fond memories of what Milton was like when I was growing up!

You’ve been reading my posts for a number of years, and that means a lot to me. As long as people like you keep reading, I’ll keep writing.

Losing touch with history is a big mistake for all of us. Having people such as yourself who won’t let go and Pursue it with passion and love is priceless for us and generations to come. I hope they recognize the treasures you will have left behind for them to enjoy and learn from.

Thank you for that!

Curt, it’s my hope that what I’ve written stays behind as my legacy when I’m gone, and I don’t care if my name is attached to the writing. Thank you for your continued interest!

My sisters and I, along with our families, also just returned from a cruise from Istanbul to Athens to Venice on the Viking Neptune. (I will be really upset if you were on the same cruise!) Our experiences, compared to yours, would be similar to the opposite panels of a triptych, with the center panel the countries we visited. We were typical American tourists — scratching our heads over the currency, snapping photos left and right, sticking out like sore thumbs. The language was all Greek to us, although I did learn enough to be able to decipher “la ola lola”. Coming up the Eastern side of the Adriatic Sea, we were fascinated by the mix of empires — Greeks, Romans, Slavic peoples, Italians, Hungarians, with religions represented by various Orthodox faiths, Muslims, and Roman Catholics. At different ports, the guides assured us that their nationality was the good guys; the others were not to be trusted!

And so, too, how you and I look at Milton is also the opposite panels of a triptych. We both are interested in Milton’s history with no personal connections . Me with deep family roots in the Milton area but never lived there; and you with no roots but living in the town and fascinated by the past.

Hey, keep up the good work and I look forward to your next Milton installment!

Rodney, are you the partner in Tunnell and Raysor? Your take on attitudes at the places you visited in the eastern Adriatic is perceptive and could open up a real can of worms if you chose to pursue a line of inquiry there. One thing that differentiates most Americans from Europeans, and especially those of the eastern Mediterranean, is how how short our historic memory is (as well as our attention span). For Greeks, the fall of Constantinople in 1453 could have happened within their lifetime. The intensity of their feeling about it will be evident when you talk to any of them as I did, starting with the conversion of the Hagia Sofia in Istanbul back to a mosque. It bothered me as well. Likewise for Serbs is the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. Both of these events have become part of the national mythology and psyche of each country, and contribute to an animosity towards all things Muslim (and Turkish) in the region. We’ve seen what has happened in Bosnia and Cyprus as direct consequence. The residual animosity between Orthodox and Catholic branches of Christianity is also there, but not nearly as potent.

With a complex history and a superabundance of national pride, it is a difficult region to understand if you apply normal reasoning and analysis to it. Nevertheless, the people were welcoming and friendly everywhere we visited, as I think they were for you.

I have no association with the Tunnells of Tunnell and Raysor. Our common ancestor is William Tunnell (1731-1776) who moved from Accomac County, Virginia, to Muddy Neck near Millville in Sussex County inland from Bethany Beach. William is the ancestor of most of the Sussex County Tunnells. But wait! There is a story here that connects to Milton. My great-grandfather Robert C. White (1851-1919) was raised on the Benjamin White farm east of Milton, went to work in Drawbridge, became a lawyer, married Laura Riley Conwell of Milton, and moved to Georgetown. After serving as Delaware’s Attorney General at the turn of the century, Robert took in James Miller Tunnell (1879-1957) as a clerk who read law and was admitted to the bar in 1907. James (Old Jim) was a life-long great friend of the White family, and named his second son Robert White Tunnell (1914-2000). Old Jim pretty much took over the law firm after Robert C. White passed away in 1919. He went on to become U. S. Senator for Delaware from 1941 to 1947. Robert White Tunnell was the Tunnell of Tunnell and Raysor, and his Tunnell relatives work for the firm today. My generation has lost contact with them, except for my daughter Ruth who until recently processed real estate loans in the mid-Atlantic region and occasionally called Tunnell and Raysor on business which turned into discussions of family history!

Back to Turkey and Greece: Yes, the people we met were all very friendly (and not just because we were paying tourists) and when they disparaged their neighbors, it was done in fun. I, too, fret that we are focusing too much on the ugly side of our history instead of working for a brighter future.

I appreciate your story . Having spent time rummaging through photographs with you, I wondered how you developed a strong tie to our town. Being a native Miltonian, your blogs have provided awareness of the people and events that shaped this town in years gone by. Thank you for sharing your interests, historical data, and stories.

Thank you for your response Martha Jane; I do what I do for folks like you.

Thank you Phil for your amazing family struggles and history. You have helped me understand so very much of my Davidson, Wilson ancestry ,in Milton,Delaware. I thank you for your LOVE of ancestry and history. Milton,Delaware will gain so much for your choosing to reside there! I loved seeing your pictures of your travels!!! Fondly, Sallie Davidson Macy

Great to hear from you Sallie, and thank you for the kind words. Family dynamics through multiple generation have a great influence on who we are today, and that is what I’ve come to realize over time.

Phil,I find it is a huge responsibility I feel to continue my Milton heritage and family history! Thank you for helping me!!!! Sallie

Great to hear from you Sallie! I don’t know if I told you before this, but the dress you gave us has been on display in the “Women of Milton” exhibition that has been on view since March and will close in December. I was so happy to have it out there finally.

I am thrilled!!!!!!! Thank you for this fantastic news!!!

Phil would you so kindly text me a photo of the dress and display, so I can share it with family? 865-216- 6294. Thanks, sallie

Done!

Enjoyed this very much, Phil. Thanks for this personal blog!

Glad you enjoyed it Sue! I rarely write this way, so I was rolling the dice on how the post would be received.