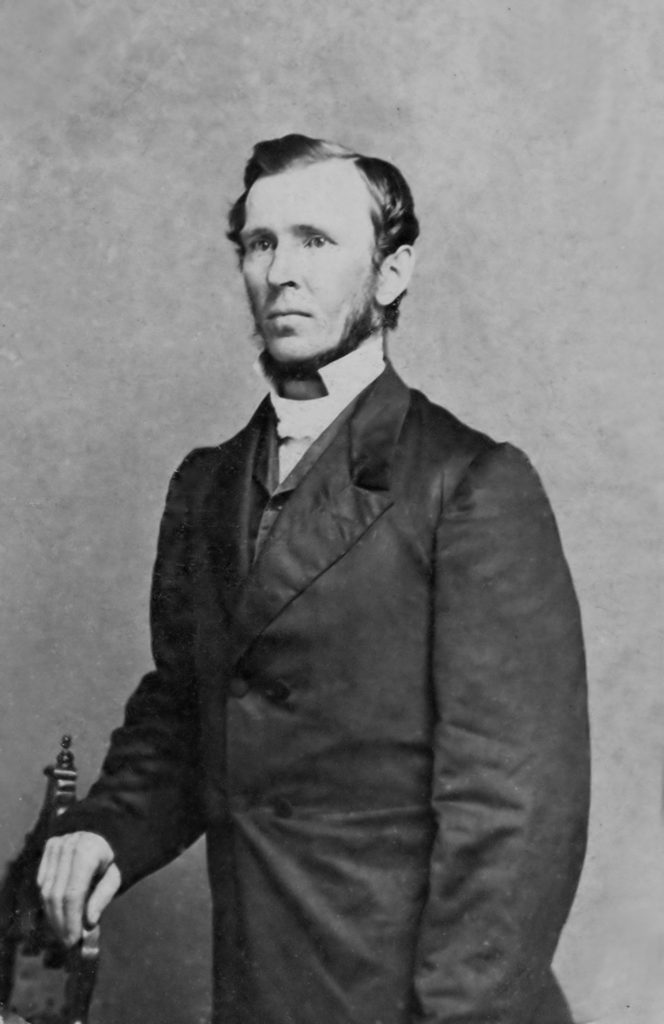

Several 19th century photo albums in the Milton Historical Society collection contain photographs of ministers that were neither family members nor direct acquaintances. Most of these clergymen are relatively obscure today, but one that is not is the Rev. Adam Wallace.

The photograph above, a carte de visite, was found in the Milton Historical Society’s collections, in the Bellows Family album. We know a great deal about Rev. Wallace through an excellent compendium of his personal recollections, with notes and a biographical sketch, titled My Business Was To Fight the Devil, edited by the Rev. Joseph DiPaolo, and published by Tapestry Press, Ltd. of Boston, MA in 1998. The book is still in print and is available at the Milton Public Library, as well as in other branches of the Delaware library system. The details of Rev. Wallace’s story are all taken from this book.

Rev. Adam Wallace’s life follows an unusual arc for a Delmarva Methodist preacher. He was born in County Fermanagh, one of the six counties of what is today Northern Ireland, and brought up in the Church of England. His family, however, had strong connections to the Wesleyan movement – the movement that would give rise to Methodism in the United Kingdom and the United States. Disenchanted with a schoolmaster that “never spared the birch,” he finished his formal education at the age of 13. In 1843, at the age of 18, he left Ireland for the United States, attracted by the stories he had heard about America. Arriving in New York City, he made his way to Philadelphia, where his life would be centered thenceforth. The rest of his family – mother, father, and three brothers – joined him by 1846, part of the massive Irish immigration brought on by the potato famine of 1845.

By the time he was reunited with his family, Wallace had undergone a new religious conversion under the influence of Rev. Levi Scott of the Union Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, and had plunged into the activities of that congregation. By the fall of 1846, feeling the call to preach, he was granted a license to exhort (act as a lay preacher), often the first step to the ministry. In 1847, hearing a “stirring appeal” for young men to serve as assistants to the preachers serving the Eastern shore of Maryland and Virginia, he signed on.

For the next 14 years – the Antebellum period of high tension in the run-up to the Civil War – he would serve as a circuit rider, or itinerant preacher, for the Philadelphia Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, under which the entire Delmarva peninsula was administered. He did not attend a theological seminary; as with many young men called to the preacher’s vocation in those years, he was trained on the job as an assistant to an ordained minister, with assigned readings mandated by the Conference and yearly examinations. He began his practical training as a lay preacher on the Snow Hill Circuit in the southernmost district of the Philadelphia Conference, centered in Worcester County, MD. By 1848, he had moved to the Laurel, DE circuit; he was ordained as a deacon in 1850, giving him the right to administer the sacraments for the first time, and was finally ordained a minister in 1852.

After his ordination, the newly-minted Rev. Wallace was assigned to the Lewes Circuit. The Lewes Circuit included the town of Milton, and it was at Milton that he was lodged, together with his new 17-year old wife, Margaret Lewis. It was also at this time and place that he made solid friendships with a who’s-who of Milton society: ex-Judge and former Governor David Hazzard, Dr. W. W. Wolfe, Dr. Joseph Maull (once a partner in Paynter’s Mill), Noah Magee, and C. Coulter, among others. He is sure to have met the family of Joseph C. Atkins, which included seven-year old Martha Emma Atkins. Martha, who in 1872 married William C. Bellows and compiled the photograph album in which we found Rev. Wallace’s picture, is the likeliest person to have acquired Wallace’s carte de visite and placed it there, but not as an child. For one thing, the carte de visite was invented in France in 1854 and did not come into widespread use until after 1859. It is far more likely that she encountered Rev. Wallace when she was an adult, at one of the many camp revival meetings that Methodists held on the peninsula, and at which famous preachers from all over the conference and beyond were invited to preach. The nearest camp meeting to Milton in the 1860’s in which M. E. ministers participated was an annual affair held at Sand Hill, a few miles south of Milton, and it is probably there that Martha acquired Wallace’s CdV.

However, the above stories are prosaic when compared to the Wallace’s experiences of the tensions between pro- and anti-slavery factions both within the Methodist Episcopal Church on Delmarva, and on the peninsula as a whole, in the years leading up to the Civil War. While the Methodist Episcopal Church was for a long time officially opposed to the slave trade, they had not explicitly spoken against slave ownership. The unofficial position was that taking a firm stand against slavery as an institution, would “rock the boat,” something that the leadership felt would inflame passions among church adherents and cause a loss of membership. However, passions were inflamed anyway: one of the church’s bishops became a slave owner by marriage, and at the M. E. General Conference of 1844 supporters of slavery and their opponents clashed over this matter. A new, southern branch of the church, supported by the pro-slavery faction, split off from the parent body. On the Delmarva peninsula, which included two border states (Delaware and Maryland) where the population was split between pro- and anti-slavery adherents, both branches of the M. E. Church claimed all M. E. congregations as their own, and tensions ran high from the 1840’s right through to the end of the Civil War.

Given this political and social environment, the life of a circuit-riding preacher on the peninsula in the Antebellum was not only physically arduous, it was dangerous. Aside from the usual rowdies and thieves, a significant number of people on the peninsula were opposed to evangelical Methodism and were hostile to its preachers. For the anti-slavery circuit-riding preachers of the Philadelphia Conference, adhering to their moral principles put them at great risk of serious harm in a confrontation with slave traders and owners.

In 1854, on the Northampton Circuit on Virginia’s Eastern Shore, Wallace and his wife came upon two white men who were attempting to bind the wrists and feet of an unresisting old African American man, “old Negro Sam,” with the intention of selling him to traders headed South. The old freedman had fallen into the road, and was being badly handled by his captors. Wallace pushed one of the men off “old Sam” and was met with a stream of invective from the other for “interfering with the sale of a slave,” and was told to mind his own business. Wallace writes in his recollection of the event that he replied to the men that it was his business was to fight the Devil, which Rev. DiPaolo adopted as the title of his book. It turned out that “Old Sam” had been freed by his former owner. The owner then died, and his widow married one reprobate and his daughter married another. After a spree, the two men found themselves out of money and decided that the old black man still belonged to the family and could be sold to get back some money. Concocting a ruse to get him alone, they enticed him with an offer of work, set upon him, and were in the process of tying him up when Wallace happened upon the scene. Unable to obtain assistance from anyone standing by, faced with two angry cutthroats, and with a frightened wife in his carriage, Wallace was unable to free the old man. Upon finding out that he was lucky not to have been knifed by the thieves, but that they nevertheless had no legal right to sell the old black man, Wallace left his wife at the parsonage and took off, alone, after the three. Arriving at Locust Mount, he found “Old Sam” held in a jail with other captured African Americans, all to be transported together to buyers in Richmond. All but one of the local lawyers he spoke to advised him to forget the matter and return home; one, however, issued a writ to have a magistrate look over the matter. To Wallace’s surprise and relief, when the magistrate heard the case a week later, he ordered “Old Sam” released.

Rev. Wallace was no fire-eating, John Brown type, but he was steadfast and firm in his belief that black members of the M. E. Church should not be relegated to the upstairs galleries, and that they should partake of the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper at the altar, instead of having the communion brought up to them. He risked the wrath and physical violence of some Delmarva Methodists on the circuit who would not abandon the institution of slavery.

When he was taken off the circuit in 1861 and elevated to the position of Presiding Elder of the M. E. Church, he continued to advocate for the rights of African American members of the M. E. Church. He was instrumental in the establishment of the Delaware Conference in 1864, the first M. E. conference to ordain black preachers and invest them with all the rights and powers of that office, as well as giving the right of ownership of church property to black congregations.

Of some interest to Miltonians is the fact that Rev. Wallace officiated at the funeral of ex-Governor David Hazzard in July of 1864. The two had become acquainted during the period when Wallace was riding the Lewes circuit (1852 – 1854) and was spending time in Milton, where Hazzard lived. Wallace had also officiated at the funeral of Hazzard’s wife Elizabeth in 1853.

The latter part of Rev. Adam Wallace’s career, from the end of his term as Presiding Elder in 1865 to his death in 1903, would followed a very different direction.

The seeds were sown in 1864, while Wallace was still a Presiding Elder, when he purchased a tiny, defunct Princess Anne County newspaper, the Somerset Union, to ensure at least one pro-Union, pro-Methodist newspaper in the lower peninsula. He did not have the time to edit the newspaper himself, and appointed others to staff the journal. However, when the paper reported injustices perpetrated by the Orphan’s Court of Princess Anne against local blacks, that news reached all the way to the White House and Congress. It resulted in the arrest, conviction and imprisonment of several judges of that court, and gave Wallace a profound appreciation for the power of the press to sway opinion and motivate readers to take action.

Rev. Wallace requested and received a posting as minister of the Salem Church in Philadelphia in 1865. In 1867, he began to edit the Methodist Home Journal, a weekly regional publication of the Methodist Episcopal Church. He asked for a received a “supernumerary” designation from the Church in 1869, after which he never again assumed the duties of church pastor or itinerant. This freed him to pursue a successful publishing venture in Philadelphia, printing his own works and those of other writers, and culminated in his acquisition and active management of the Ocean Grove Record in 1874. Ocean Grove, NJ, founded in 1869, is the oldest continuously active Camp Meeting association in the U. S., and Wallace was a co-founder and enthusiastic proponent. The town was a Methodist-oriented alternative to secular seaside resorts such as Atlantic City, and proved to be very popular.

Wallace continued write and manage the Ocean Grove Record, and to accept speaking engagements until well into his seventies, by which time he was considered an “elder statesman” of the M. E. Church.

Mr. Martin, thank you so much for your extensive research on Rev. Wallace. We especially enjoyed his remarks at Gov. Hazzard’s funeral. This is important history of Milton and the area that we need to know. You continue to enlighten us on Milton’s history that many of

us would never have known without your thorough research.

Judy, I had a feeling you would like the sermon and obituary on David Hazzard, as you own a substantial piece of Hazzard’s history. I haven’t been to a church service in a very long time, so maybe I’ve forgotten what church sermons are like, but I don’t ever remember hearing one as well constructed as Rev. Wallace’s. That was a different age, though; many of the faithful would have been very familiar with the quotations from scripture and from the Methodist hymnals that Wallace interspersed throughout his sermon, and the better educated among them would certainly have known Bryant’s poem; not so today. How the minister worked these elements into his characterization of David HAzzard is remarkable to me. I’m also starting to think that, based on what I’ve read from 19th century and early twentieth century writers with some erudition, it was not an uncommon style of writing. It may also have been the model that David A. Conner followed in many of his columns; he was a churchgoing man, and sermons would have been his most frequent contact with literary forms of exposition (although he wasn’t always successful making his point this way!).

As long as you keep reading my posts, I’ll keep writing them! Thanks for your support, as always.

Truly fascinating. He was my 3rd great-grandfather and have been trying to get further back in his lineage to no avail. If you know of any resources that speak about his upbringing, location and family, I would be most appreciative. Thank you very much for the illuminating article!

Tod, my primary source for this post was the book My Business Was To Fight the Devil, edited by the Rev. Joseph DiPaolo, published by Tapestry Press, Ltd. This title is mentioned in the article, near the beginning. As for going further back into Adam’s lineage, you might consult ancestry.com.

Mr. Martin, you are doing a fine job despite professing to have no credentials as a historian. You use primary documents, link to museum holdings and the community, don’t make wild claims, and write in a very compelling manner. Keep up the good work. I learned something about the famous and enigmatic “Jints” in a later blog. Well done.

I am interested in Rev. Wallace’s writings for his experiences as an anti-slavery preacher in the Laurel area. Also, interesting to hear about the influence of Rev. Levi Scott, as we begin a project at Scott AMEZ in Wilmington, a church named to attract the interest of Reverend Scott (which it did).

Debra, I’m delighted to hear from you, and thank you for the kind words. I do try to do the best I can. Regarding Rev. Wallace, I can take a look at his writings, which are in the Milton Historical Society’s collection, and photocopy anything relevant to his experience in Laurel and whether he openly spoke against enslavement. It was a dangerous thing to do in Sussex County before the Civil War; the overwhelming majority of enslaved persons in Delaware lived in Sussex County, and the sympathies of the locals were sharply divided between North and South. I’ll get back to you in a few days; I’m in the midst of preparing a new exhibition for the Lydia B. Cannon Museum here in Milton.

Check Joe DiPaolo’s recent comment for some info about Rev. Scott

Phil: Just saw this again after a few years and read the more recent comments. Good stuff. I don’t know if Debra was aware of my book on Bishop Scott published in 2018, called Wide Views and a Loving Heart. Would be happy to get her a copy if she contacts me. I also was reminded of your discovery of the CDV collection at Milton Historical Society. Do you have a list of the photos of ministers you discovered in them?

Good to hear from you! I’ll make sure Debra knows about your book, and I’ll look at the CDV inventory to see how many preachers pop up. One I know is Rev. Turner (no first name given).