In the late 19th century, Milton boasted three pharmacists: Thomas H. Douglass (who left the profession in 1895 to start the Douglass and White Shirt and Overall factory), John B. Welch, and William T. Starkey. By 1900, standards of education and practice had been developed by the American Pharmaceutical Association, the U. S. Pharmacopeia (a compendium of medicines) had been developed, and pharmacy schools had been established in major U. S. cities. The manufacturing of medicines was shifting away from formulation by individual pharmacists to mass production, pioneered by the Parke, Davis & Company of Detroit.

Despite these steps, a large number of drug stores were little better than shops that sold tens of thousands of drugs and tonics over the counter. Some these drugs were pure quackery and snake oil, but other remedies were actually of some value and are still used today. We don’t know the extent to which Milton’s druggists received a modern pharmacy education or if they attended a pharmacy school. However, The Milton Historical Society has several dozen medicine bottles from the 19th century in its collection, many of which still retain their labels; I will focus on a few of these as a sampling of some popular remedies in the Victorian era.

Painkillers

By far the most prevalent painkillers in the 19th century were opiates. They were available with or without prescription, in grocery stores, by mail order, or mixed in with countless patent medicines. In the last case, there was no notification on the label that the medicine contained an opiate; indeed, none of the ingredients were required to be listed until after 1906. One modern writer referred to 19th century America as a “drug fiend’s paradise.”

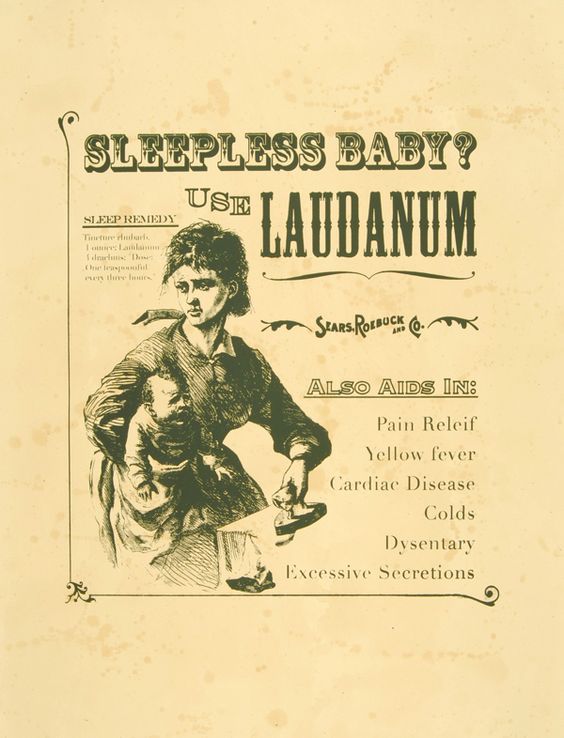

Laudanum

In a recent episode of the PBS series Mercy Street, set in Alexandria, VA in during the Civil War, the patrician southern belle Jane Green says to her servant, “Belinda, fetch my laudanum.” It was a harrowing day for her, and laudanum was a way to cope. One hears the name of that drug in almost any television series set in the 19th and early twentieth centuries, such as The Little House on the Prairie, The Knick, Ripper Street and Deadwood, to name only a few, as well as in innumerable works of fiction and films. It turns out that laudanum was an extremely popular – and highly addictive – analgesic, sold over the counter, and as ubiquitous as aspirin and Xanax are today. Laudanum, in fact, was taken for pain and anxiety, among many other things.

Laudanum is a 10% solution of powdered opium in alcohol: potent, addictive, and believed by many to be a cure-all, as can be seen from the Sears Roebuck advertisement above. Known since the 15th century, it provided some relief for pain, coughing and severe diarrhea, which was a boon at a time when tuberculosis, cholera epidemics and widespread rheumatism brought suffering to many. It was used as a sleeping aid, for colds, flu, menstrual cramps and infant colic. In the 19th century it became an ingredient in many patent medicines and was mixed with almost anything imaginable. The list of famous persons who were addicted to it is long and impressive: Mary Todd Lincoln, Samuel Taylor Coleridge , and Elizabeth Barrett Browning were seriously addicted, while Bram Stoker, Charles Dickens, George Eliot, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Lord Byron were known regular users who extolled the drugs euphoric virtues.

After 1914, opium and its derivatives were increasingly regulated, putting an end to the practice of secretly mixing laudanum with other substances to sell as patent medicine. Physicians could still prescribe it for treatment, but it ceased to be an over-the-counter purchase. The drug’s only use today is as a treatment for severe diarrhea, and is likely to be phased out of that usage soon.

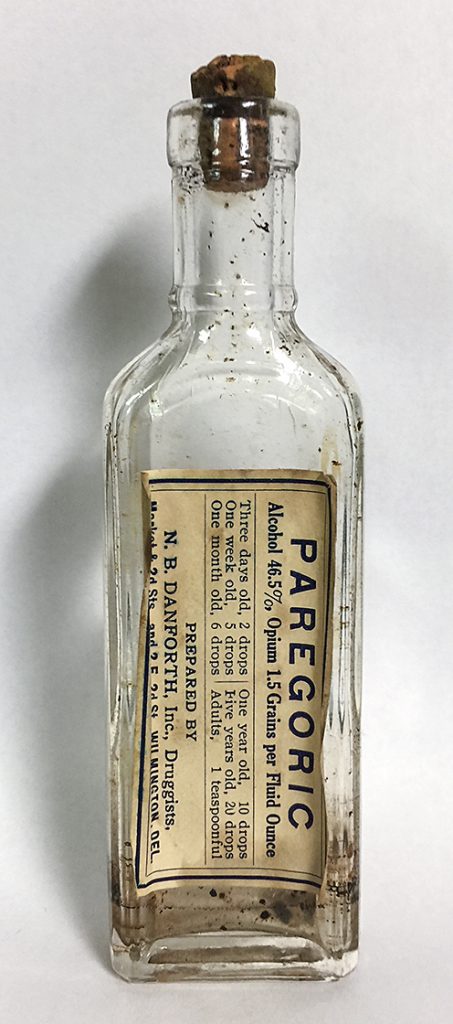

Paregoric

A close relative of laudanum, paregoric has been familiar to Europeans and Americans since the 17th century. The drug’s name comes from the Greek word παρηγορικο, which means to soothe over (in oratory); the name is apt for a drug that has analgesic, antidiarrheal, and antitussive properties. As with laudanum, paregoric is a tincture of opium powder, but is 4% opium as opposed to 10% in laudanum. In addition, anise oil, benzoic acid, camphor, and glycerin are added to the tincture. As a child in the 1950’s, I remember being given paregoric whenever I had a bad bout of stomach flu; if I recall correctly, the drug did what it was supposed to do, although it tasted vile.

The drug was a household remedy throughout the 18th and 19th century, as common as aspirin today, and was used not only for severe diarrhea and coughs, but also to soothe infants with teething pains and to calm fretful children. After 1914, paregoric fell under the same Federal regulations as all drugs containing opiates, but was available without prescription in the U. S. until 1970, when it was categorized as a Class III controlled substance. It is still available by prescription today, and has found yet another use: the treatment of babies born to opiate-addicted women.

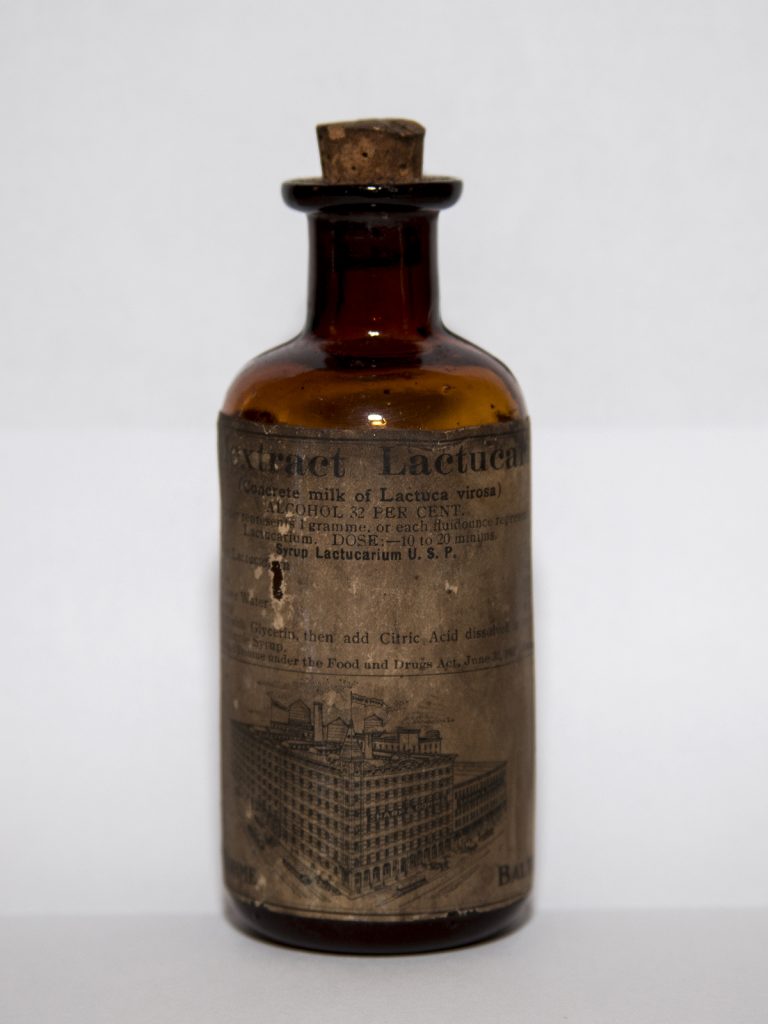

Extract of Lactucarium (aka Lettuce Opium)

One of the oddest of 19th century drugs was Lactucarium Extract, which was obtained from the milky white secretion of the Lactuca Virosa plant – commonly known as lettuce. “Lettuce Opium,” as it is sometimes referred to, has been known since the time of the ancient Egyptian as an analgesic and mild euphoric. Introduced into the United States in the 19th century, it was thought of as an alternative to laudanum and other opiate-based drugs, although less potent.

Studies in the twentieth century were highly critical of the efficacy of commercial lactucarium; the alkaloids in the substance that have analgesic effects were unstable and did not last long in commercial formulations. Its use has largely faded away today, but in the 1970’s it was touted as a legal psychotropic drug by hippies.

Tonics and Other Remedies

Tonics and patent medicines that purported to cure or alleviate all manner of complaints were tremendously popular in the 19th century. A few of them actually had some practical value and are still sold today.

Kurokol

Kurokol was a cough syrup that contained alcohol, chloroform, and cannabis (marijuana), which could have referred to either Cannabis sativa or Cannabis indica. The medical use of the cannabis plant can be traced as least 3,000 years; by the late 1880’s, cannabis was used frequently in cough syrups and related medicines and this continued to be the case until the 1930’s. Cannabis was valued as a pain killer and sedative that was also capable of drying up, expanding and unclogging the throat and air passages, without causing the constipation or depressed respiration associated with morphine.

As with most other patent medicines, none of the ingredients were listed on the label, which dates this particular bottle to pre-1906. After the Food and Drugs Act, all the ingredients, including cannabis, were listed. The drug was recommended for children as young as a year old.

Most of the information available today for Kurokol can be found on cannabis advocacy web sites. Ironically, after 70 years of prohibition, the sale of cannabis for medicinal purposes has been legalized in many states.

Fennel Seed Extract

Fennel, which originated in the Mediterranean but now is grown worldwide, has been used for culinary purposes for thousands of years. It has long been thought to have medicinal value for the treatment of various digestive problems including heartburn, intestinal gas, bloating, loss of appetite, and colic in infants. It is also used for upper respiratory tract infections, coughs, bronchitis, cholera, backache, bed-wetting, and visual problems. Some women use fennel for increasing the flow of breast milk, promoting menstruation, easing the birthing process, and increasing sex drive.

Fennel used for medicinal purposes is today sold as an herbal supplement.

Dessicated Spleen

Spleen extract is given “as replacement therapy” in cases where the spleen has been surgically removed or isn’t working properly.

People with low white blood cell counts, cancer, infections, or HIV-related infections take spleen extract to boost the immune system.

It is used as well for treating “autoimmune” diseases such as celiac disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), dermatitis herpetiformis, and rheumatoid arthritis. Some people use spleen extract for a kidney disorder called glomerulonephritis, a blood disorder called thrombocytopenia, an intestinal disease called ulcerative colitis, and a blood vessel condition called vasculitis.

The vendor of this bottle, the Armour Company, was a meat packer based in Chicago. The company’s divisions have been sold off over the last hundred years, but one can still find the Armour brand on packages of hot dogs.

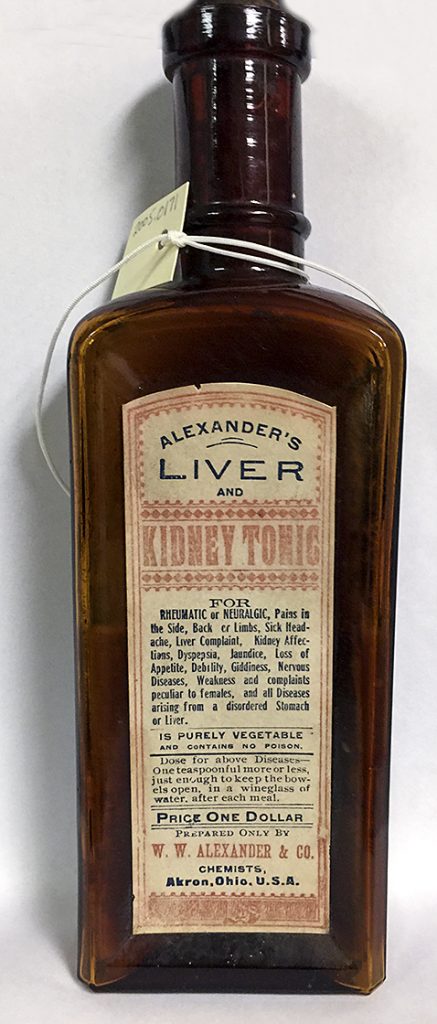

Alexander’s Liver and Kidney Tonic

Tonics that purported to cure or alleviate all manner of complaints were tremendously popular in the 19th century. The W. W. Alexander Company was one of many firms that produced patent medicines and tonics. The patent medicine shown above was produced from about 1885 to 1906. It is interesting to note the statement “IS PURELY VEGETABLE and contains no poison” on the label. This can be interpreted to mean that there are no opiates in the formulation, but what “vegetable” ingredients were included is not apparent.

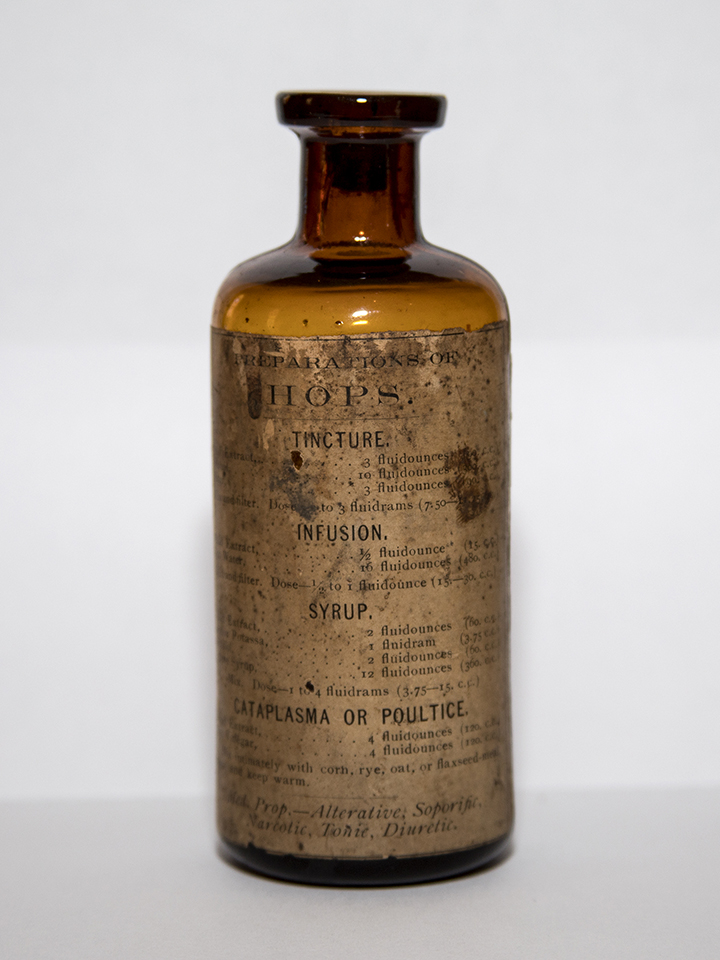

Hops

Beer lovers are quite familiar with hops, which add a desirable bitter edge to the brew. What is not common knowledge is that hops have a medicinal value as well, similar to valerian, as a treatment for anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia. The soporific effects of hops have been known since at least the middle ages, thanks to monks who added them to the beer they brewed to reduce their sex drive. A pillow filled with hops is a popular folk remedy for sleeplessness.

The label on this bottle indicates the use of hops as a soporific (sleep aid) as well as a diuretic. Curiously, the label characterizes hops as having narcotic properties; if the bottle contains hops only, then the term “narcotic” is probably a misstatement of soporific effects.

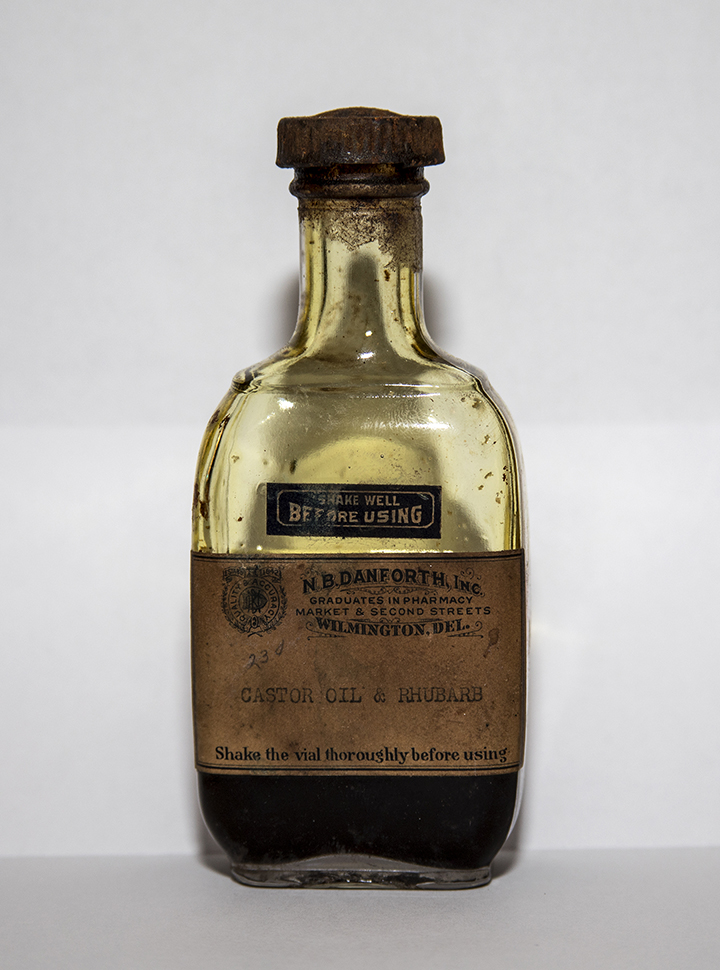

Castor Oil

A vegetable oil, castor oil is obtained by pressing the seeds of the castor plant. It is deemed today by the FDA to be a safe and effective laxative, no doubt one of the uses to which it was applied in the 19th century. There is no scientific evidence of its effectiveness against other ailments.

One of the more sinister uses for which castor oil was used was as punishment, for children who misbehaved and for recalcitrant servants in the British Raj. In one episode of the PBS series Indian Summers, it was administered to the household staff of a colonial official to determine who stole a piece of jewelry; as it turns out, none of the staff were responsible for the theft. It also appeared every so often on the old TV series Little Rascals, as a punishment for children’s misbehavior; this practice was discouraged by doctors, who did not want medicine to be seen by children as punishment. Perhaps the most infamous example of castor oil as punishment was in Mussolini’s Fascist Italy, when it was force fed in large amounts to political prisoners, many of whom then died from the rapid dehydration brought about by massive diarrhea.

The bottle above contains both castor oil and rhubarb; the latter was also thought to be a laxative, so a mixture of the two would have been thought potent.

———————————————–

Sources:

Wikipedia articles

National Museum of American History catalogue listing of Alexander’s Liver and Kidney Tonic

Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs

WebMD articles

Your blog is nice but i do not see any bottles from Milton. What is MHS doing with bottles from all over the U.S.?

MHS has unlabeled bottles in their collection from the J. B. Welch and William Starkey pharmacies, where the druggist’s name is embossed in the glass. However, the blog post was about the “medicines” themselves, not so much the bottles. It would have been nice to include a few photos of patent medicines in labeled bottles from Starkey, Welch or Douglass.