More than once, an artifact or a photograph has propelled my into a line of inquiry that takes off in unexpected directions. I ran across the cabinet card shown above at the Mercantile in Milton, and I bought it to add to my own collection of 19th century photographs. The name of the subject was hand-written on the back—Lillian Lewis Postles, along with her age (7 months)—something uncommon in the photographs I find in antique shops. My curiosity naturally took over, and I started researching the name. By the time I completed that research, this baby girl turned out to have been the owner a 333 year old family farm once owned by Kent County Quakers who took a moral stand against slavery in Delaware.

As it turns out, there are a dozens of newspaper articles about Lillian Lewis Postles, her husband Dr. George Roland Miller, and their daughter Dr. Mary Emily Miller, starting in the WWI era and continuing into the 21st century. The cabinet card portrait of Lillian Lewis Postles (1899 – 1970) can be dated to about 1900. The photographer, Russel C. Holmes (1852 – 1927), was well known in Dover and did portraits in crayon as well as photographic work for decades. This is one of the earliest examples of a central Delaware photography studio’s work that I have run across; most other late 19th and early 20th century Delaware studio portraits have come from out of state (i.e. Philadelphia), from Wilmington studios, or were made by itinerants.

Lillian, the daughter of Robert R. Postles (1868 – 1948) and Mary Abigail Eberhart (1874 – 1938), was what we today call a “gifted” child and stood out from her peers in Frederica, where she was raised. Family background was not a good predictor of her future; Robert Postles was a commercial fisherman for much of his working life, while her mother kept house. As a teenager, she was recognized for her dramatic talents as well as her academic achievements. She attended several colleges, including the University of Pennsylvania, and finally settling on Syracuse University from which she graduated in 1924. Trained as an educator, she took her first job with the Friends School in Wilmington after graduation, as an English teacher at the intermediate level.

In 1925 she married George Roland Miller (1894 – 1991), already established as Superintendent of Schools in Mountain Lake, NJ. She moved with him there and put her career on hold. There was an interlude in which the Millers resided in Asheville, NC, where he was an instructor at a junior college, but in the early 1930’s, they moved back to Delaware when George accepted the position of Superintendent of Kent County schools. He would go on to serve in similar positions in the state for 33 years before his retirement, and Lillian would teach in five different Delaware school systems. As a footnote, Dr. George R. Miller’s doctoral thesis at New York University, focusing on Kent County schools, demonstrated that black schools were separate from but not equal to white schools. The thesis was used in support of the plaintiffs in the landmark 1954 Supreme Court case of Brown vs. Topeka Board of Education.

The biography of George and Lillian Miller is a tale of exemplary public service. However, things really get interesting when daughter Mary Emily Miller (1934 – 2015) starts receiving attention in the press. Every bit as intellectually talented as her parents, she graduated from the University of Delaware in 1955, then received a Master’s degree and her PhD from Boston University in 1962, in history. She would be involved in the academic world all her life, specializing in maritime history, even after retirement from her final position at Salem State College in Massachusetts. Late in her life, newspaper articles began to appear about her research – apparently over a period of decades – on the family farm which was passed on to her by her mother. In the course of that research, she unearthed a fascinating family saga of the Emersons, of which she is a direct descendant on her mother’s side.

That story begins in 1684, when Jacob Emerson buys land from Benony Bishop, one of the ten original holders of land grants from William Penn, in the Murderkill Hundred. The Kent County census of 1688 lists Jacob Emerson, his wife Margrett, and their 5 year old son living on 150 acres, presumably what Emerson bought from Bishop, who had an estate of 1050 acres. Fast forward to 1757; the land bought by Jacob Emerson in 1684 is still owned by the family, and Jacob’s grandson Gouverneur (“Govey”) Emerson (1730 – 1773), his wife and six children are received into the Society of Friends – the Quakers – at the Duck Creek Meeting, near Smyrna. The conversion to the Quaker faith would have social and financial ramifications for his children.

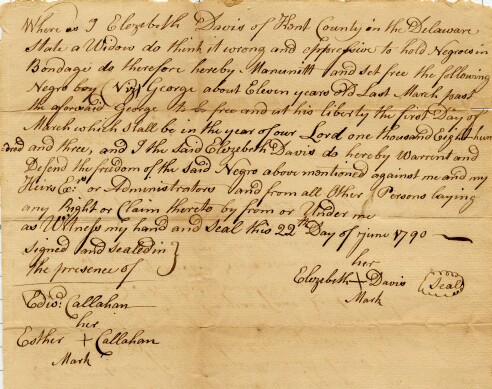

The Methodists and other Protestant denominations grappled with the slavery question well into the 19th century, but the Quakers were unequivocally opposed to the ownership of other human beings. Delaware in colonial days and after the American Revolution was a slave-holding state, but in the latter part of the 18th century manumissions – the setting free of slaves – occurred at a record pace in Kent County. The Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Quakers, to which the Delaware branch belonged, declared itself opposed to the slave trade and later to slave ownership itself. They recommended that all Quakers free their slaves, and then in 1776 made it mandatory. This was probably what moved two of Govey Emerson’s sons – Govey (1756 – 1809) and Jonathan (1764 – 1812) – who were farmers and slave owners in Kent County, as well as observant Quakers, to take a stand. They made provisions in their wills to free their slaves, and gave explicit directions to their executors to do whatever it took to provide for the slaves’ freedom. Jonathan Emerson went so far as to provide restitution to his former slaves for the work they did for him while in bondage. Slaves had a significant asset value to any owner, and their manumission came at a cost in both lost property value and the expense of ensuring they could make a start in life. Quakers, however, were quite willing to make this financial sacrifice in light of the perceived righteousness of doing so.

The Jonathan Emerson I just spoke of was the great-great-grandfather of Lillian Lewis Postles, and the great-great-great-grandfather of Mary Emily Miller. At the end of her life, Mary Emily Miller was the sole owner of the farm that was first acquired by Jacob Emerson in 1684. In the maternal side, she was a descendant of the Emerson line; she did not, however, come by the inheritance directly in an unbroken chain. The property landed in Orphan’s Court (“Surrogates Court”) in 1835, from whence it was acquired by Joseph Israel Lewis (1800 – 1872), who was not a descendant of the Emersons. Lewis willed the property to his daughter Mary Ellen Lewis, who left it to her daughter Mary Abigail Eberhardt. The latter married George Postles, who was an Emerson descendant. Their daughter Lillian Lewis Postles received the land from her mother Mary Abigail, thus bringing the land back into the Emerson family after a gap of several generations. Lillian and husband George Miller finally left the farm to Mary Emily Miller, who did not have any children. As a result, the final owner of the farm put it into a Charitable Remainder Trust, to ensure that it remain a working farm, with the property eventually to be given to the University of Delaware.

In 2016 Delaware artist Mark Reeve produced several paintings celebrating the oldest farms in Delaware. The Miller farm was among the paintings, and both Lillian and Mary Emily Miller are portrayed in front of their farmhouse. For copyright reasons, I cannot show the painting directly in the blog, but you may use this link to view an image of the painting.

The Millers – Lillian, George, and daughter Mary Emily – have had a significant impact on the local as well as the national level, and deserve to be remembered for their contributions. Lillian and Mary Emily’s ancestors in the Emerson line, Govey and Jonathan, also deserve our recognition for doing what many of their contemporaries could not do – divest themselves of their slaves, and find release from the poisons of the institution of slavery. They were well ahead of their time.

I hope to have a photograph of the Miller farm as it looks today in a subsequent post.

Sources

Wilmington Evening Journal, 1914 – 1962

A Sketch of the Life of Dr. Gouverneur Emerson, William Samuel Waithman Ruschenberger, 1891

Kent County, Delaware: Quaker Influences on Slavery, Denise A. Horner, Shoreline Journal, November 2010, Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture at Salisbury University

http://www.hagley.org/about-us/news/mary-emily-miller-1934-2015

http://www.capegazette.com/node/83660

http://www.overfalls.org/HOF/MHOF_2011.html

http://archive.americanfarm.com/TopStory10.03.06a.html

This is a fascinating article. I have long been interested in the history of the Quakers in the antislavery movement. I wonder if the Quaker abolitionist John Woolman (1720-1772) influenced this family. He was born in Mount HoIly, N.J. and I believe he traveled through the Delmarva peninsula, going as far south as N. Carolina. I know that he spoke in Easton, MD…see http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc5400/sc5496/051800/051881/html/51881bio.html

Thank you for the work you do to bring local history to life.

—-Christine Crutsinger

Thanks for supporting the work I do. Christine – it means a lot! I did not catch any reference to John Woolnsn in the sources I used; it seemed to be an abolitionist directive from the Philadelphia conference that prompted the manumissions. However, I will look into your link and see what more I can learn.

One of my sisters just sent this article to me. My parents rented the farmhouse from Dr. Miller and were good friends with him. I remember meeting his daughter and being very impressed by her when I was rather young. Our family loved that farmhouse and my father tried to buy it but of course Dr. Miller would not sell. My parents eventually bought a house in Frederica and many times my brother and I would enter the woods behind town and walk to the farm just to see it again. My sisters and I even went back once and asked the people renting at that time if we could come in just to see it again. I have many happy memories of roaming the woods and visiting the deserted farmhouse behind that one. Today, March 28, 2018, I drove by and noticed that the farm had been burned down and that a logging company now owns the land. At least there was a sign from the logging company at the end of the lane and a no trespassing sign. So sad to see it go. Thank-you for your article. It was wonderful to read the history. My family lived there for more than 10 years.

Thank you so much for the information in your blog. I have been recently delving into the history of my Emerson roots in Delaware. Jonathan Emerson 1764-1812 is my great great great great grandfather. I can now add his father and grandfather to my tree, and other information from the sketch of Dr Gouverneur Emerson. The Emerson’s married with the Howells which is where I get my last name from.