I have often stated that my primary source of information about the life of the town of Milton in the early 20th century was David A. Conner’s Milton News letter in the Milford Chronicle. Thanks to a project undertaken by the University of Delaware in the 1980’s, with the support of the National Endowment for the Humanities, many Delaware newspapers printed as far back as 1781 were microfilmed. Among these was the Milford Chronicle. In the last few years, the University of Delaware has been digitizing much of this microfilm to make newspapers available on line to a much wider readership. Not every publication was preserved in this way, however.

From 1897 to 1916, Milton residents had their own hometown paper, the Milton Times. Unfortunately, this publication was never microfilmed; only a scant few printed editions survive, of which the Milton Historical Society has a handful. The paper ceased publication decades before the microfilming project was begun, and its printed output was evidently discarded when the newspaper’s assets were sold off.

The Milton Times was launched in 1897 by L. Henry Wilkinson, who then sold it to Theodore Messick in 1899. Messick in turn sold the paper to Walter W. Crouch in 1901. Crouch, a printer by trade, knew how to put out a newspaper, and he ran it until 1911. In that year he found a rather unusual buyer – the Rev. Charles A. Behringer Sr., rector of St. John Baptist Episcopal Church on Federal Street.

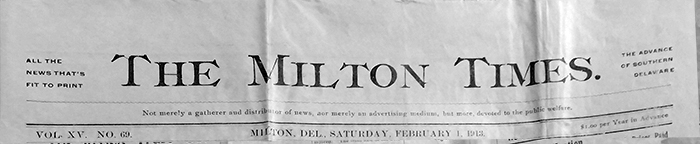

No one can say for certain what motivated Behringer to put out a weekly, but there are some clues to his ambitions in the masthead. On the left side, the slogan “ALL THE NEWS THAT’S FIT TO PRINT” is a shameless bit of plagiarism. Originated by newspaper magnate Adolph Simon Ochs, it was and still is the slogan of the New York Times, which first used it in its October 25, 1896 issue. It was an explicit rejection of “yellow dog” journalism, and an aspiration to a higher quality of reporting. At the bottom of the masthead appear the words “NOT MERELY A GATHERER AND DISTRIBUTOR OF NEWS, NOR MERELY AN ADVERTISING MEDIUM, BUT MORE, DEVOTED TO THE PUBLIC WELFARE.” This subheading can be viewed as an elaboration of the New York Times slogan, but there aren’t enough surviving issues of the Milton Times to determine whether the public welfare was effectively served. We can guess that Rev. Behringer wanted a bully pulpit in newsprint to complement the sermons delivered from his ecclesiastical pulpit.

Walter Crouch’s masthead contrasts sharply with Rev. Behringer’s; as publisher, the only additional wording Crouch added to the masthead was “WE HEW TO THE LINE, LET THE CHIPS FALL WHEREVER THEY MAY.” The simple, familiar phrase, originating in the woodcutting craft (the “chips” were wood chips), was proverbial by Crouch’s time, and can be loosely understood as “We do what we need to do, and whatever happens, happens.” Crouch was not the first to use this phrase in a newspaper, however; it appeared in the Daily Cleveland Herald on July 15, 1835, and was used in many contexts after that, including other newspapers.

As to the relative merits of the Milton Times under Crouch’s leadership versus under Behringer’s, that is a conversation for another day. My focus in this post is on the commercial advertising that appeared in the February 1, 1913 edition. The ads tell us which of Milton’s retail enterprises had sufficient resources to place print advertising. The canneries and wholesalers, for the most part, did not have need for print advertising to consumers, and the smaller shops most likely couldn’t afford the cost. For example, no millinery shops, of which there were at least three in Milton at the time, advertised in the Milton Times.

What follows is a sampling of the ads by local businesses that appeared in the February 12, 1913 issue of the Milton Times. Unless otherwise noted, all of the images were obtained from the Milton Historical Society,

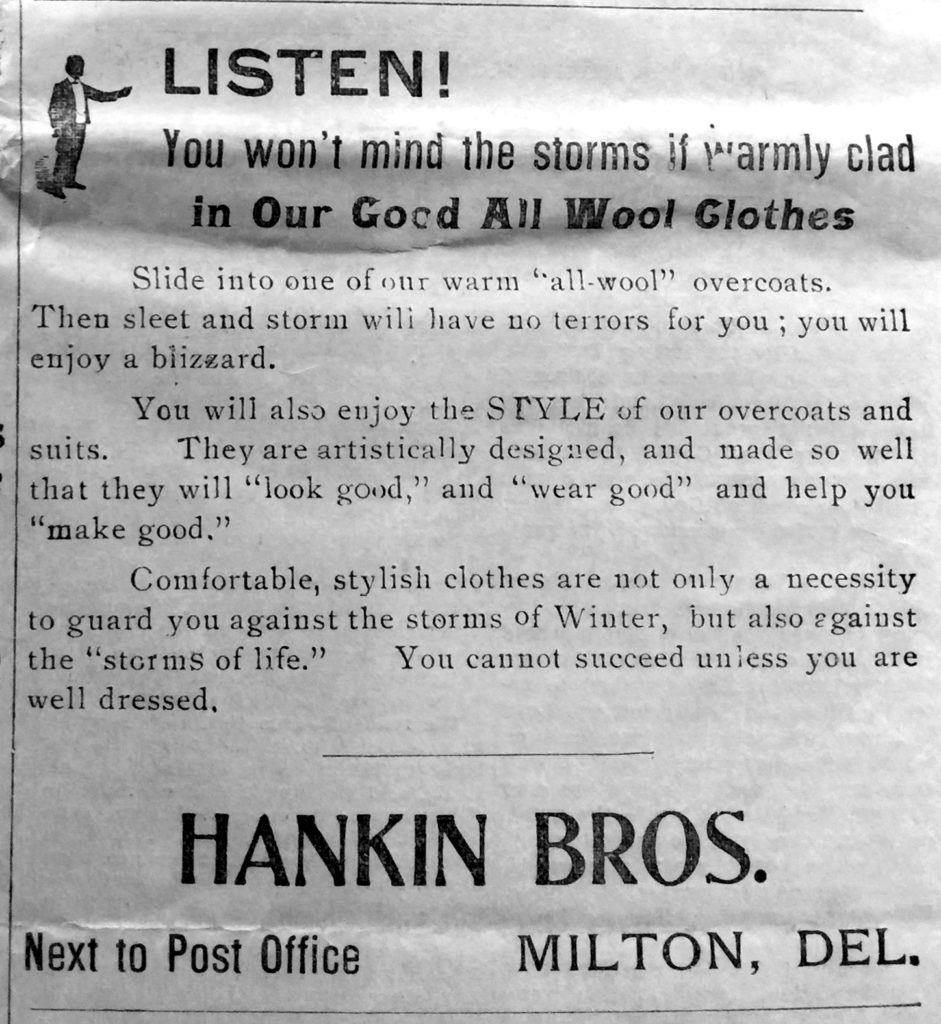

One ad that immediately grabbed my attention was placed by the Hankin Brothers store. In my previous post about Aaron and William Hankin, I had not yet found an example of their print advertising; David A. Conner mentioned their clothing store occasionally in the Milford Chronicle, but this was ad was proof positive that they really conducted business in Milton. The location given, “next to the post office,” which was then located on Federal Street, indicates that they had not yet moved to the larger space in the Chandler Building on Union Street.

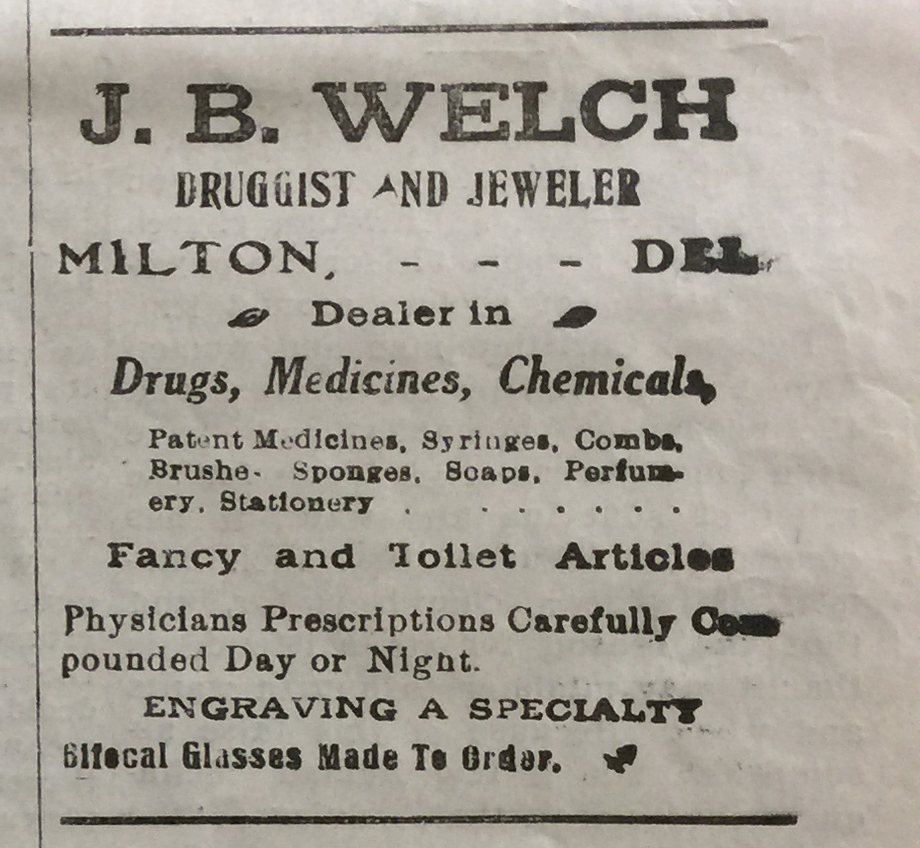

Another ad was placed by J. B. Welch, the “Bard of Milton,” who ran a drug store, made bifocal glasses, and sold jewelry when he wasn’t busy composing hymns and poems that brought him acclaim in southern Delaware. His emporium at 205 Union Street has been a private residence since the Welch family terminated business operations in the 1980’s.

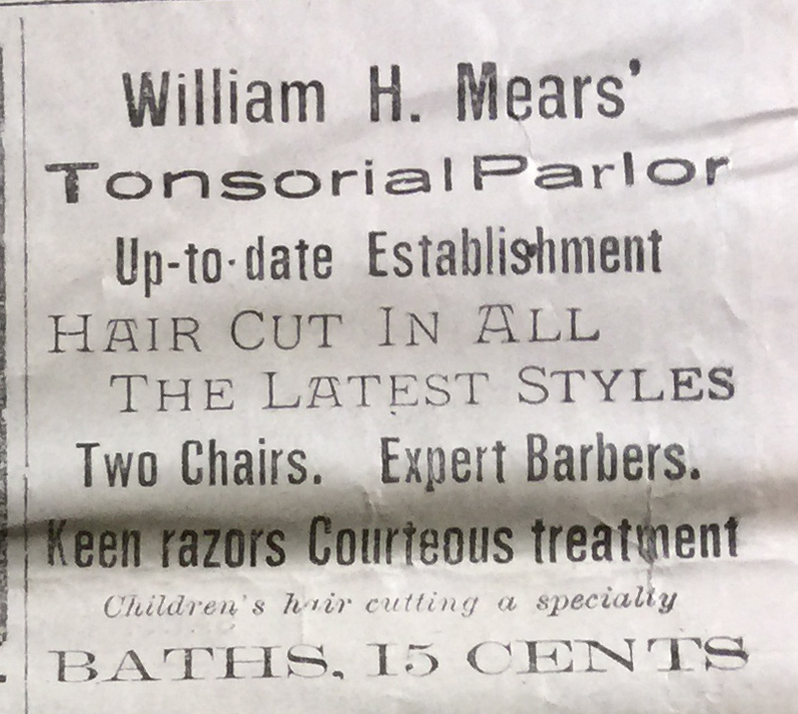

Another ad was placed by William Mears, the barber of Federal Street. Burned out of his first establishment by the 1909 fire, he rebuilt shortly thereafter what are now the two stores and residence of 102 – 106 Federal Street. What is curious about this ad is that it offered baths for 15 cents, something I have not run across before in my readings of this period. Apparently, hot and cold baths were a common service available in the barber shops of the day for both men and women, although this ad does not say whether the Mears Tonsorial Parlor allowed women to bathe on the premises.

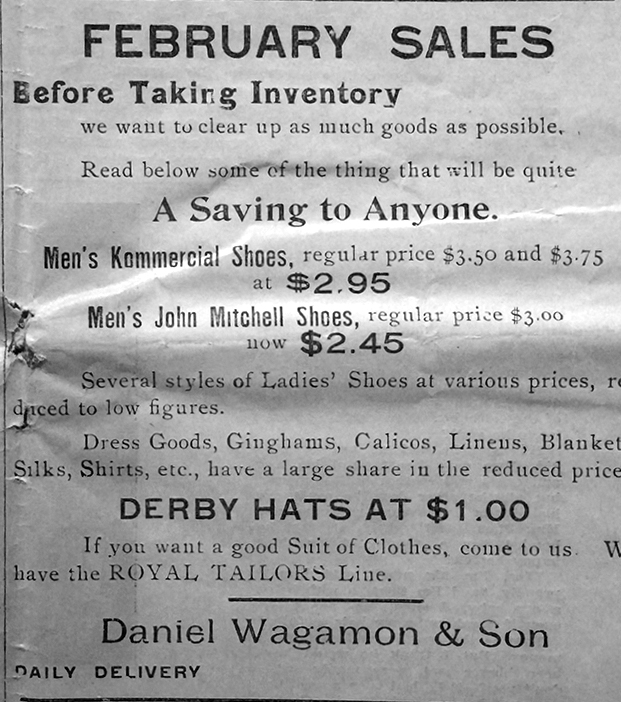

Milton had no shortage of menswear establishments in 1913. One of the Hankin Brothers’ several competitors was the Daniel Wagamon & Son clothing store, which also sold men’s and women’s shoes, linens, blankets and the like. Daniel Wagamon was the brother of H. K. Wagamon, and together they bought and rebuilt the mill on what is now called Wagamon’s Pond. in 1910, Daniel sold his interest to his brother and founded the clothing store

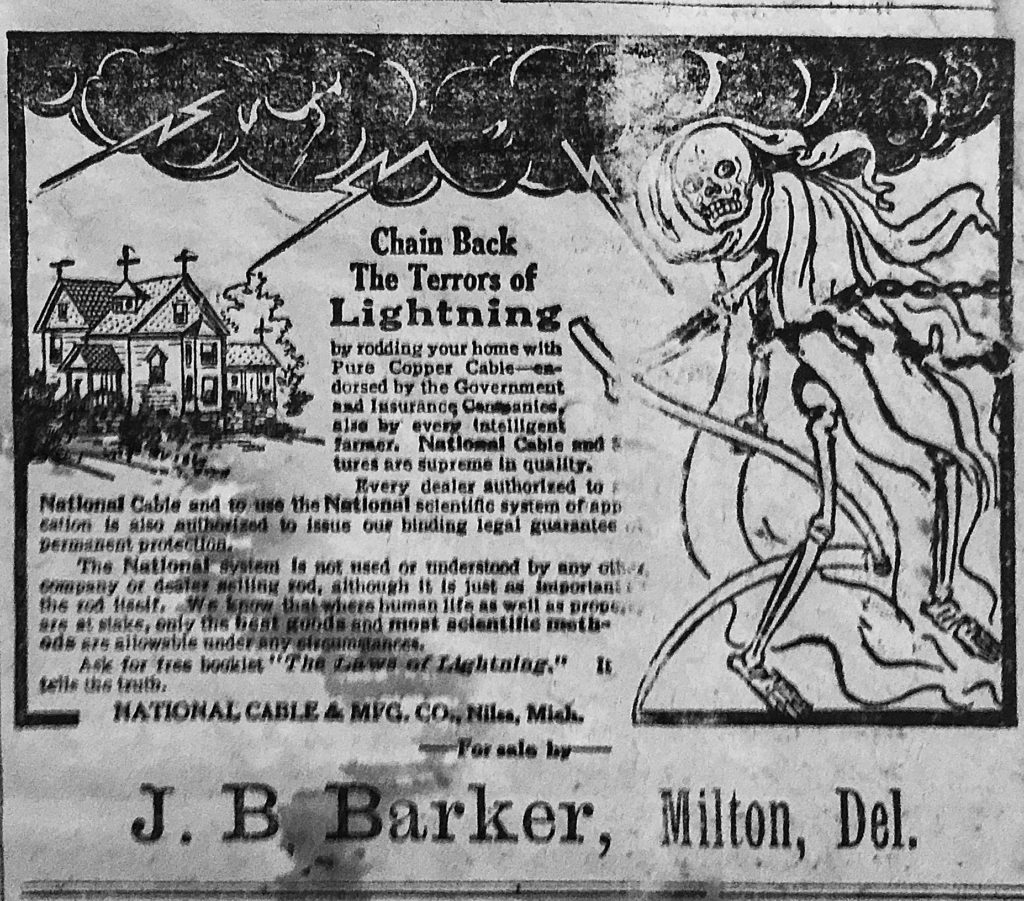

John Barker, trustee of the Milton Methodist Protestant Church and a hardware dealer, also advertised in the Milton Times. In the ad below, he preys upon the fears of local residents regarding lightning strikes, which were commonplace and destructive.

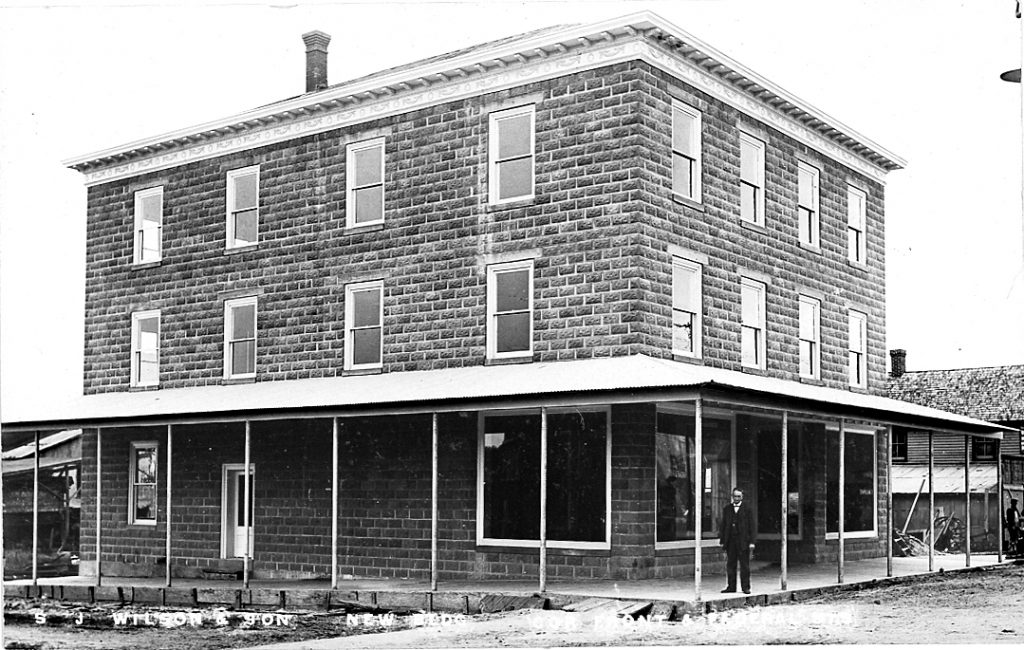

No discussion of Milton retail business in the late 19th and early 20th centuries can be complete without Samuel J. Wilson. In the aftermath of the 1909 fire which destroyed his business as well as most of the others in the downtown area, Wilson rebuilt on the corner of Front and Union Streets, across the street from the firehouse. His two-story building housed a furniture store as well as his undertaking business.

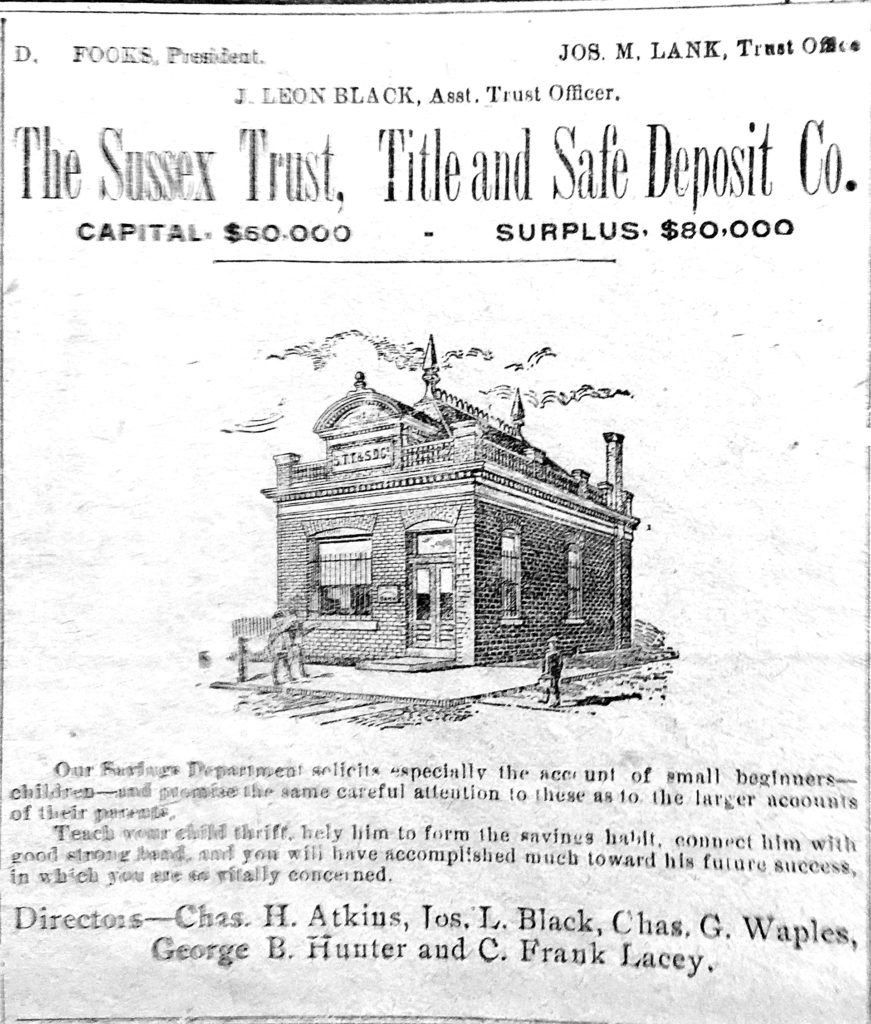

The Sussex Trust, Title and Safe Deposit Co., headquartered in Lewes, built a branch office on Federal Street in 1901. That building, the only one of the downtown commercial buildings that was built of bricks, survived the 1909 fire and still stands. Its exterior is largely what it was since it was first constructed.

I love reading your blogs. I grew up here. My mother’s family was Darby.

We have been here so long I dont know for how long. She told me many things about her tes here from 1915 to 1981

Helen, It’s always good to hear from you and the other Milton people who have deep roots here. Did your mother leave you any photos, letters, postcards, or diaries, or other artifacts from the early twentieth century? If so, I would love to look at them, and possibly use some of these materials in a future blog post. I rely a lot on visual content for the posts, because many people do not have a long attention span for reading textual content (our generation does, but I am not sure of those that followed us).

I always look forward to your blogs. Your history lessons are interesting.

Thank you for your support! I’m taking longer between posts because I’m trying to keep them interesting.

I’m a new Miltonian and want to thank you for the enlightening articles on your blog.

Mike, I’ve made the correction.

Thank you for keeping us up to date with the past…you can’t know where you are going unless you fully understand where you came from.

..and even then, with all that we have supposedly learned, we still repeat the mistakes of our predecessors again and again. Thanks for your interest!