In my previous post, I provided an overview of the American Legion Honor Roll of 1949. First installed in front of the Post building on Rt. 16, the tablet was moved to the front of the Lydia B. Cannon Museum on Union Street sometime between 2005 to 2006, when the Museum was extensively remodeled.

Today I’d like to delve more deeply into the individual stories of the men whose names are engraved on the Honor Roll tablet. I will not be doing so by going down the names in listed order; instead, I will look be looking at service branch and theater of operations. At first glance, it would seem that the names are in chronological order by date of reported death, much like the Vietnam War Memorial on the Mall in Washington DC. However, with the lack of biographical details associated with some of the names, it is unclear whether the assumed chronology is accurate. As more information hopefully surfaces, I will revisit this.

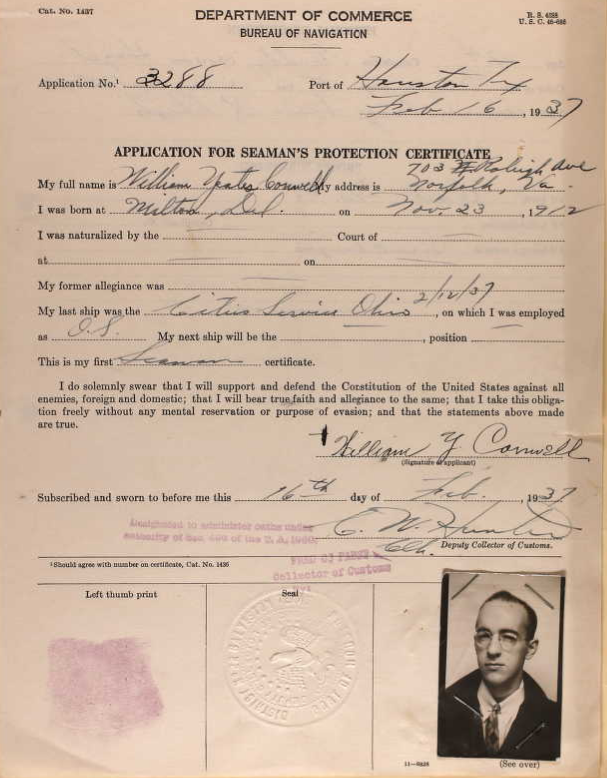

I will begin with the first confirmed Milton death of World War II: William Yeates Conwell (12/23/1912 – 4/23/1942), a seaman in the Merchant Marine. Anyone familiar with the town’s history will recognize the prominence of the Conwell family name in the maritime industry through many generations. On his mother’s side, William was descended from another illustrious line of Milton sea captains: the Megees. Drawn to the sea, William obtained a seaman’s protection certificate in 1937.

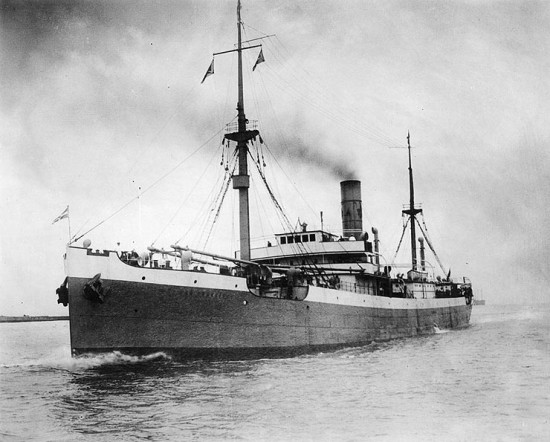

Five years later, William Y. Conwell was part of the crew of the Lammot Du Pont, commanded by Robert Cameron Housten. Despite the fact that the United States was at war with the Axis powers, and German U-boats were sinking Allied shipping at an alarming rate, the Lammot Du Pont was unescorted. She was on a voyage from New York to Buenos Aires, Argentina, far from the European conflict, but nonetheless fair game to any U-boat captain.

The following account is excerpted from uboat.net, a site devoted to documenting the hundreds of sinkings of Allied shipping by U-boats during WWII, as well as the destruction of U-boats by Allied naval vessels.

At 20.53 hours on 23 April 1942 the unescorted Lammot Du Pont was hit by one torpedo from U-125 when steaming on a nonevasive course at 9.5 knots about 500 miles southeast of Bermuda. The torpedo struck on the port side between the #4 hatch and the engine room. The explosion blew the booms at the #4 and #5 hatches onto the deck and threw a large column of water and linseed in the air. The ship rapidly listed to port and within five minutes rolled completely on her side. The nine officers, 36 crewmen and nine armed guards (the ship was armed with one 4in and two .30cal guns) began to abandon ship in one lifeboat and three rafts. Six crew members went down with the ship and two left on a broken raft. The other survivors tried to reach these men in the heavy seas, but they drifted away and were never found.

Eight crew members and seven armed guards on two rafts were picked up after two days by the Swedish motor merchant Astri and were transferred on 8 May to USS Omaha, which brought them to Recife, Brazil on 11 May. The 31 crew members and two armed guards in the lifeboat drifted for 23 days before being rescued by USS Tarbell, after being spotted by an aircraft about 40 miles from San Juan (Puerto Rico), but seven crew members and one armed guard already died of fever and three other crew members later died in a San Juan hospital.

Conwell appears to have been among the crew members found adrift on the lifeboat after 23 days. He was reported as having died of exposure, probably before the lifeboat was spotted and the mariners rescued.