The “Flying Dutchman”- a legendary ghost ship – was a product of Dutch maritime ascendancy in the 17th century, with the story actually written down in the 1700s. Mariners have always been a superstitious lot, but this is one tall tale that has a basis in reality. While the ghost ship had a crew doomed to forever wander the seas and never make port, there were many instances of “ghost ships” wandering the sea lanes, right down to the last years of wooden sailing ships in the modern era. The oft-repeated scenario went like this: a wood-hulled ship that had seen a lot of hard years in service would start losing the caulking that kept sea water from leaking in between its timbers; bilge pumps and manual bailing could provide a temporary solution, but eventually these methods would not keep water from entering the hull at a faster rate than it could be pumped out. When that limit was reached, especially during rough seas, the crew would be forced to abandon ship. However, ships that carried buoyant cargo such as lumber would not necessarily sink; instead, they would remain afloat, moved along by wind and currents, posing a navigation hazard for weeks or months until they were salvaged or scuttled.

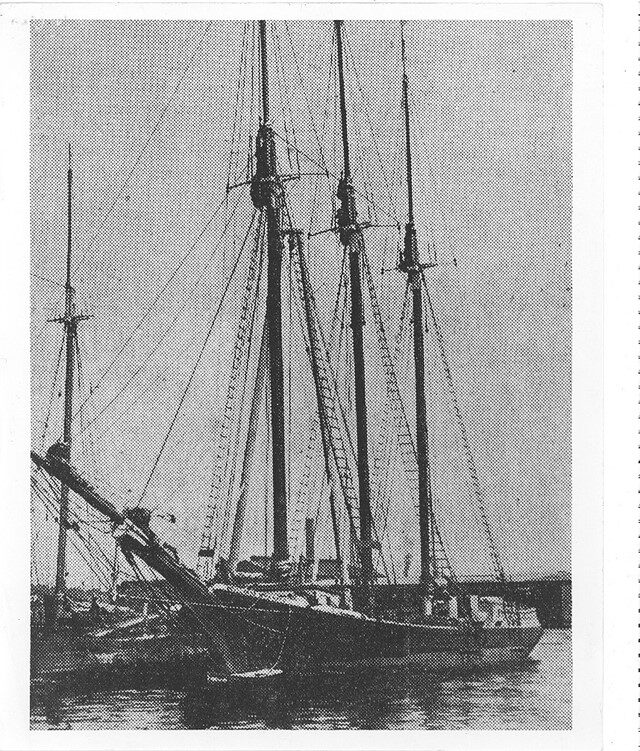

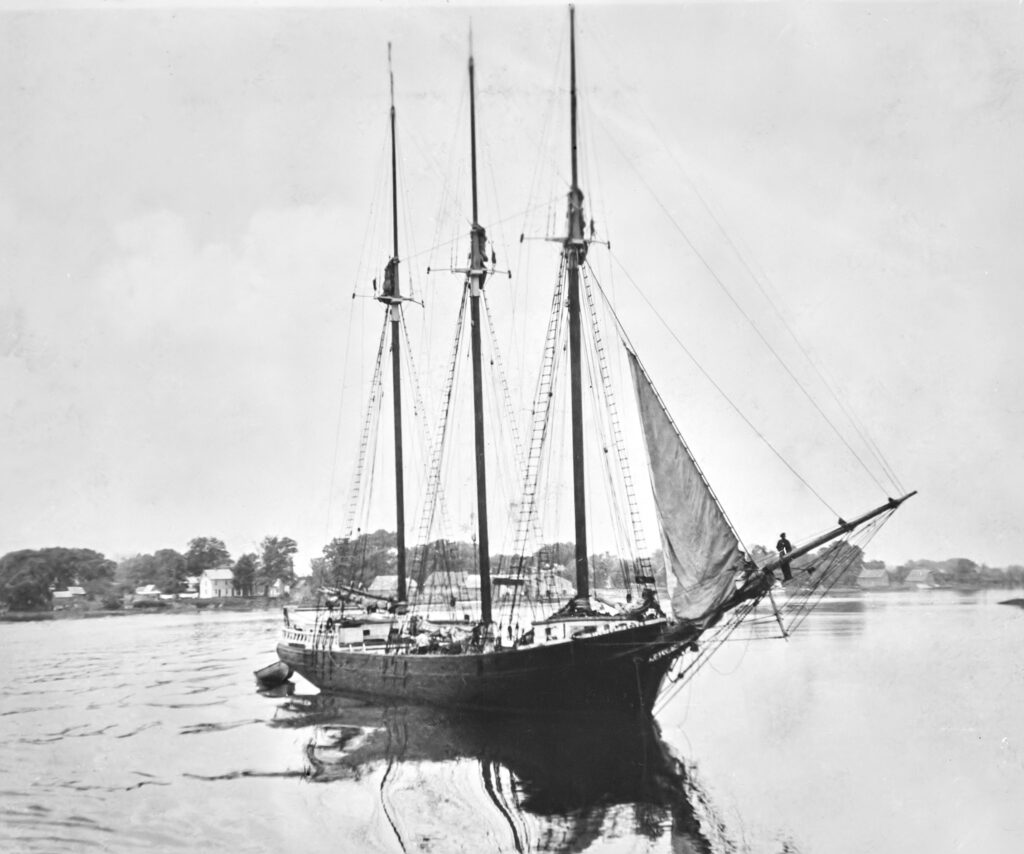

The William T. Parker, built in the Milton shipyards by C. C. Davidson in 1891, was destined for decades of service which would include a stint as a ghost ship. A prolific shipbuilder, the Parker would be among the last of Davidson’s projects, and one of the last schooners to be built here. Davidson was an expert builder, and his carpenters fastened the ship’s timbers in such a durable fashion that she served well beyond the average life expectancy of a wooden ship. Among the shareholders were Charles A. Burrous, the captain; Capt. John R. Megee, who we have met before (see the post O Captains, My Captains!), and William T. Parker. The latter investor had a large share (25%) and got to name the ship after himself.

With three masts and a shallow draft even when fully loaded, the Parker appears to have been intended for trading in places with shallow channels. This kind of navigation was inherently risky, but the Parker had remarkably few mishaps in her first 7 years of service. In 1899, her luck suddenly changed with a series of 9 incidents of being stranded, most of them off Cape Henlopen. The last of these resulted in her capsizing twice in the course of being towed to Camden, NJ for repairs. She was pumped out and resumed service.

From 1900 to mid-1914, the vessel did not encounter severe difficulties. However, the Baltimore Sun reported that in 1915, the crew of the Parker abandoned ship off the coast of North Carolina, believing her to be sinking. The report goes on to say that the vessel did not, in fact, sink; she drifted up to the Maine coast, where she was sighted but no one realized she lacked a crew. The ship then caught a current in the opposite direction and almost made it back to North Carolina, again without a crew, and was “wrangled” off Chesapeake Bay and towed into Baltimore Harbor. This “Flying Dutchman” chapter of the Parker’s life story has been repeated by Maryland marine experts in the modern era and makes for a fascinating tale, except there are no contemporaneous accounts of the supposed ghost voyage. The Baltimore Sun report mentioned at the top of this paragraph appeared in print on December 15, 1946, more than thirty years after the supposed ghost voyage; it reads like a third hand, uncorroborated account.

The only clue that something may have gone wrong is the total absence of any reports of the comings and goings of the Parker from June 26, 1914 to December 30, 1915. This is highly unusual for a working coastal schooner, as such a ship would be sailing into and out of its home port quite frequently. Such comings and goings of vessels were reported in port city newspapers as routinely as weather forecasts are reported today. Even had the ship been involved in litigation, forfeiture, a bad accident or an extended repair period, it would almost certainly have been reported by the Baltimore Sun, since Baltimore was the Parker’s home port. This gap in an otherwise detailed narrative is puzzling, to say the least.

Regardless of whether she drifted that far or not, the Parker’s age was beginning to show by the end of WWI. In the mid-1920’s her topmasts were removed, apparently a common practice for sailing ships with old masts and rigging. The most reliable account I can cite, T. C. Conwell’s Ships and Men of the Broadkill, says that the Parker remained in service well pass her fortieth year, continuing to move cargo in and out of Chesapeake Bay. The death blow came on the night of February 25, 1935, when she was rammed by the SS Commercial Bostonian off Bloody Point, Chesapeake Bay. While she made it to Baltimore harbor and unloaded her cargo, the damage from the collision was deemed irreparable.

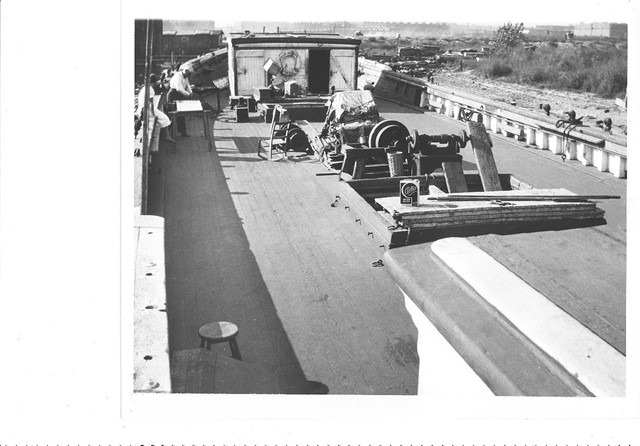

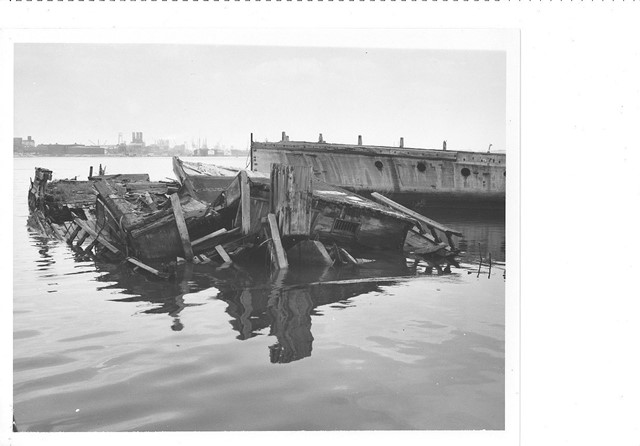

What may not be known to many readers is that Baltimore Harbor’s coves are a graveyard for scores of ships. Many of them are WWI-era wooden ships whose construction was funded through a Federal crash program to get them built and sailing quickly; the intent was to offset serious losses of merchant ships to U-boat activity in the Atlantic. The majority of these ships never proved seaworthy and lie at the bottom of the harbor where they were sunk. The Parker had its masts cut off after the collision of 1935 and served as a floating workshop and living quarters for a sailor at Curtis Creek, but after a second collision in 1951 the ship was deemed too dangerous for anyone to live on it. It sank into the creek in steady progression, until only a very small piece of it remains above the surface today.

Sources

Ships and Men of the Broadkill, T. C. Conwell

Photographs from the T. C. Conwell Collection, Milton Historical Society

newspapers.com

Library of Congress, Chronicling America

ancestry.com

A fascinating read! Almost as if this ship had an uncanny will to stay in service.