Milton history buffs – the hard-core ones, among whom I count myself – have always questioned the story that our town was named after John Milton (1608 – 1674). There is no reliable documentation I’ve ever seen that supports the case for the town’s being named for the 17th century English poet, but that did not prevent the commissioning some years ago of a life-sized statue of him, which sits under a pergola on Governors Walk. It was the subject of a recent tongue-in-cheek Cape Gazette piece about its adornment with a leprechaun costume for St. Patrick’s Day; as of this writing, the statue has been re-costumed at least twice. The Cape Gazette printed an article by Jody Dengler on July 5, 2018 that tried to bring out a little more about the qualities of the poet that would have created enthusiasm in 1807 for re-naming “Head of the Broadkiln” to “Milton.” It barely scratched the surface of the subject, but then again the Gazette is not a literary journal. At the risk of stirring up a tempest in a teapot, I am going to look at the issue again.

I’ll begin with the hypothetical scenario that the 18 men (let’s refer to them as the Broadkill 18[i]) who petitioned the state legislature to change the town’s name to Milton were actually familiar with the poet’s work. There is nothing in the petition about honoring the poet, but for this thought experiment let’s assume that was their unstated intent. What did the Broadkill 18 see in John Milton’s work that would have elicited a desire and a consensus among them to name a town in his honor?

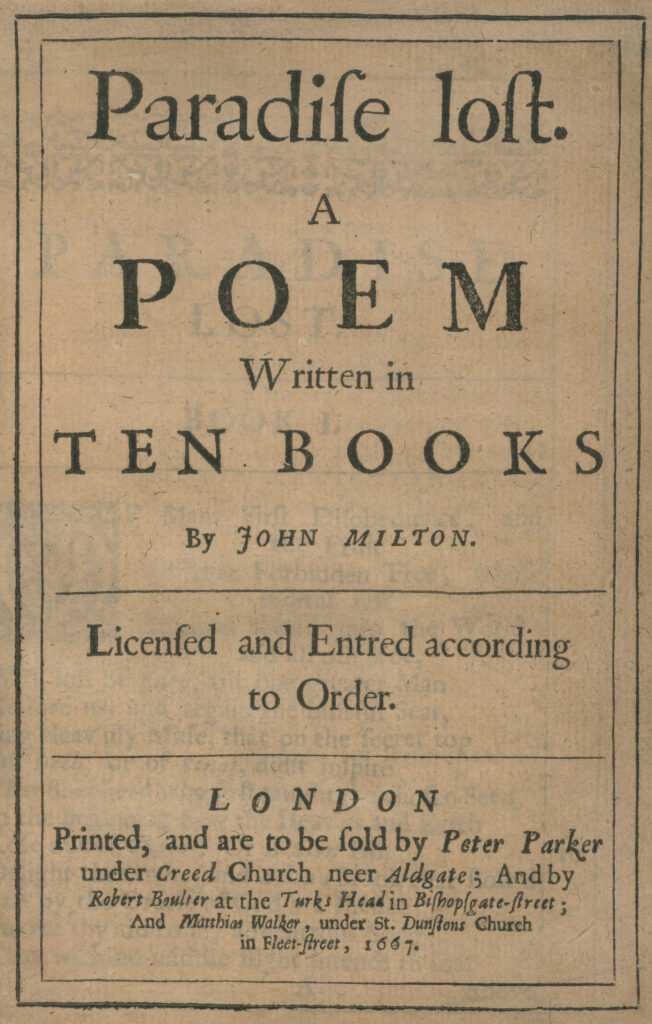

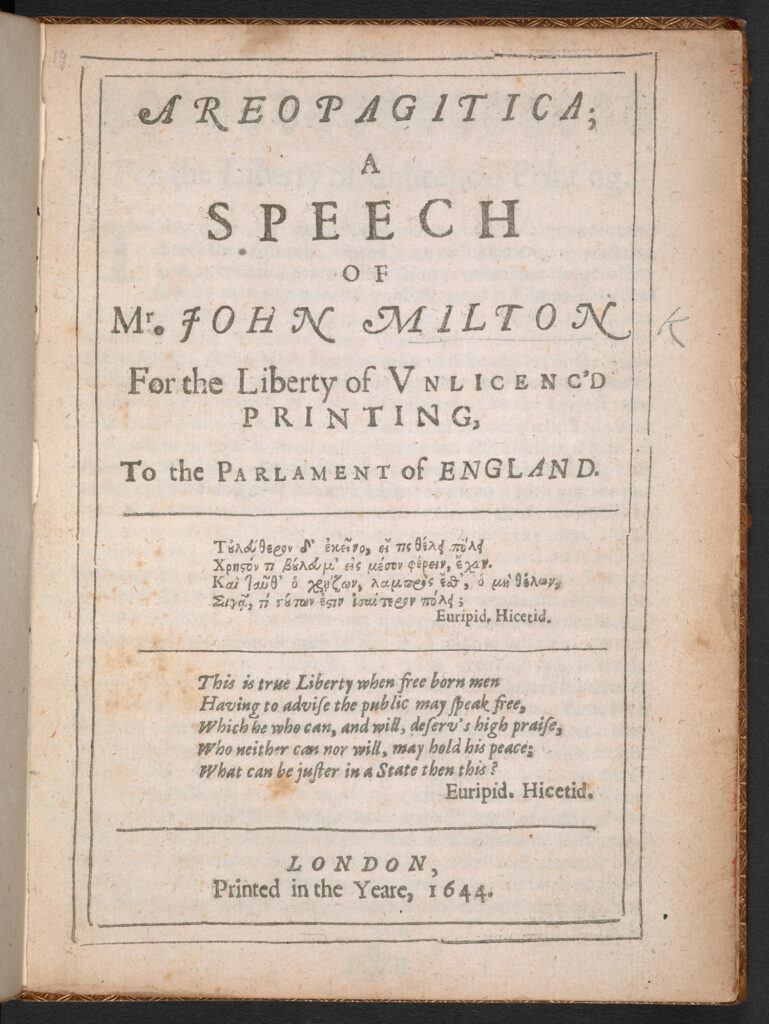

Indeed, which of John Milton’s works would have been familiar to the early 19th century citizens of Head of the Broadkiln? He published between 1632 and 1671, much of that work being political pamphlets and poetry commissioned by the aristocracy for special occasions. Two of his works, however, stand out among the rest and have had a long-lasting influence on English letters. One, of course, is Paradise Lost, his epic masterpiece, of which at least the name is familiar to many even if the poem is rarely read; the John Milton statue under the pergola is holding a volume of that work. Another of his prose works, Areopagitica, is little known today outside academic circles but no less important than Paradise Lost for its subject matter. If the Broadkill 18 had read any of John Milton, these two works I believe are the likeliest candidates.

I decided to read both Paradise Lost and Areopagitica see if these works “spoke” to me, in the hope that I could discern something in them that would have made them important to at least some of the Broadkill 18. In the interest of full disclosure, I was never an English major and have no expertise in analyzing 17th century literature, so my view should be taken as that of a rank amateur; my reactions are purely at an emotional level and skewed toward 21st century popular culture. I should also note that none of John Milton’s works are on the shelves of the Milton Public Library; I had to have Paradise Lost brought in from elsewhere in the Delaware library network, while Areopagitica was available on the internet. However, before I say anything more about either Paradise Lost or Areopagitica, I feel it is necessary to look at the historical context that shaped Milton’s intellectual development.

He was born during the reign of James I, successor to Elizabeth I, and came of age during the reign of Charles I. During his lifetime, the three wars that comprised the English Civil War were fought, Charles I was deposed and executed, a short-lived republic was established, and the Stuart monarchy restored. The nearly two decades from 1641 to 1660 during which all of these major upheavals occurred were fraught with peril for anyone who took a public stand on one side or the other. This period is when Milton published Areopagitica and began writing Paradise Lost.

John Milton was middle class, and possessed a formidable intellect. His father, John Milton Sr., was a successful composer and scrivener (copyist and notary), which allowed him to provide a private tutor for his son. While father and son were both Protestant, the younger Milton’s tutor introduced him at an early age to religious radicalism in the form of Puritanism. When he was thirteen, Milton attended St. Paul’s School in London, where he began his study of Latin and Greek. He attended Christ’s College at Cambridge, obtaining his baccalaureate in 1629 and his Master of Arts degree in 1631 in preparation for becoming an Anglican priest. In his first year at Cambridge, he was briefly “rusticated” (suspended) for quarrelling with his tutor. Despite his disdain for the stilted pedagogical methods of his school, by the end of his time at Cambridge he had added Italian, French, Spanish, and Hebrew to his command of tongues. His deep erudition in ancient and modern languages, philosophy, literature, history, and theology would be unmistakably evident in his prose and poetry. He did not enter the priesthood, however.

From 1632 to 1639, Milton dove deeply into a self-study program in all of the academic disciplines he had already mastered at Cambridge. This time included a 15 month grand tour of continental Europe which included mingling with the intellectual elites of Rome and Roman Catholicism, and direct exposure to the republican models of government in Venice and Geneva. He returned to England in 1639 as the Bishops’ War was about to begin. This conflict was just a prelude to the series of wars and rebellions that are collectively referred to as the English Civil War, lasting from 1642 to 1651.

These wars pitted Royalists against Parliamentarians, and involved Wales, Scotland and a rebellion in Ireland notable for the brutality of both sides. The initial issue was to find the correct balance of power between Parliament and the monarchy, a political stalemate that was only resolved in 1649 when Charles I, in custody since 1645, was executed. For a few years, England was the only country in Europe not ruled by a monarch; it was a Commonwealth ruled by Oliver Cromwell, essentially a military dictatorship. The Commonwealth did not survive Cromwell’s death in 1658 for very long, and Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660 to bring stability back to the country.

Milton had been writing poetry in Latin while in school and abroad, and wrote poetry in English commissioned by aristocratic patrons for elaborate parties. His early poetry was not published until 1645. It is for his political tracts and polemics that he first became known. The first series of these in 1641 attacked the hierarchical governance structure of the Anglican Church, arguing against bishops in favor of the Presbyterian model of elders. In 1643, perhaps prompted by the desertion of his first wife, he wrote a series of pamphlets arguing for the legality and morality of divorce beyond grounds of adultery. It was this series of writings that got him into hot water with the authorities.

State control, i.e. censorship of printing, was instituted during the reign of Henry VIII and continued into the 17th century. The practice was strengthened with the passage of the Licensing Order of 1643, a requirement that any material to be published had to be reviewed and approved (“licensed”) by the government prior to publication. Milton published his pamphlets anonymously and unlicensed, violating the law[ii].

In his defense, he published an impassioned plea for freedom of speech and freedom of expression, thought to be the first of its kind, which he titled Areopagitica, a reference to a 5th century B.C.E. speech by the Athenian orator Isocrates. Milton’s Areopagitica is written as a speech to the members of Parliament, but in actuality was intended to be read by them in pamphlet form. It is loaded with classical Greek, Roman and Biblical references which Milton used to support his case, and makes it difficult to read for a modern audience without extensive supplementary notes. The core arguments are very clear, however. First he states that the Greeks and Romans, founders of Western civilization, punished blasphemous and libelous authors after their writings were made public, but never felt the need to review and approve writing beforehand. Second, he states that the only entity to have enforced pre-publication censorship was the Roman Catholic Church and its Spanish Inquisition. This was a clever stratagem on Milton’s part, in that the members of Parliament were for the most part Puritan and fiercely anti-Catholic; any association of their legislation with “Popery” would be highly distasteful. Milton was ultimately trying to make the case that reasonable, thoughtful men had the ability to read and become familiar with all writings and reject those that were antithetical to their world view, blasphemous, or libelous.

Areopagitica, in my opinion, is the one tract written by John Milton that has direct relevance to American political thought, most obviously in the formulation of the First Amendment to the Constitution that enshrines freedom of speech and expression. However, Milton is not typically cited as providing the philosophical underpinnings to the First Amendment or any other element of the Constitution or the Declaration of Independence; that is ascribed to the great philosophers of the Enlightenment, Englishman John Locke and Frenchmen Jean Jacques Rousseau and Montesquieu. If I entertained the notion that the Broadkill 18 named their town after John Milton because of his defense of freedom of speech and expression, there is no evidence to support it. Milton’s other tracts were written in defense of English republicanism and against the monarchy, but it is a great stretch to draw parallels between the complexity of what was going on in England in the mid-17th century and what would transpire in America a century later.

That leaves Paradise Lost to consider. Many critics have called it the finest epic poem in the English language and undoubtedly John Milton’s masterpiece. Were the Broadkill 18 familiar with it, and if they were, what drew them to it?

Until the publication of Paradise Lost, there were few epic poems in the English canon. Among these are Beowulf, written in Old English and, in translation, is much more frequently taught in schools than Paradise Lost;Edmund Spenser’s Faerie Queene;William Davenant’s Gondibert;and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Troilus and Ciseyde.[iii]. In terms of epic poetry written in modern (post-Shakespearean) English, even in our own day, Paradise Lost is on the top shelf.

What makes Paradise Lost different? For one thing, all of its more than 10,000 lines are written in blank (unrhymed) verse, the first English language poem to have use this scheme; only playwrights had used blank verse prior to that. Just a few lines in, Milton writes “Sing, heavenly muse..” echoing the first words of the Odyssey, and a few lines later writes

…I thence

Invoke thy aid to my adventurous song,

That with no middle flight intends to soar

Above the Aonian mount, while it pursues

Things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme.[iv]

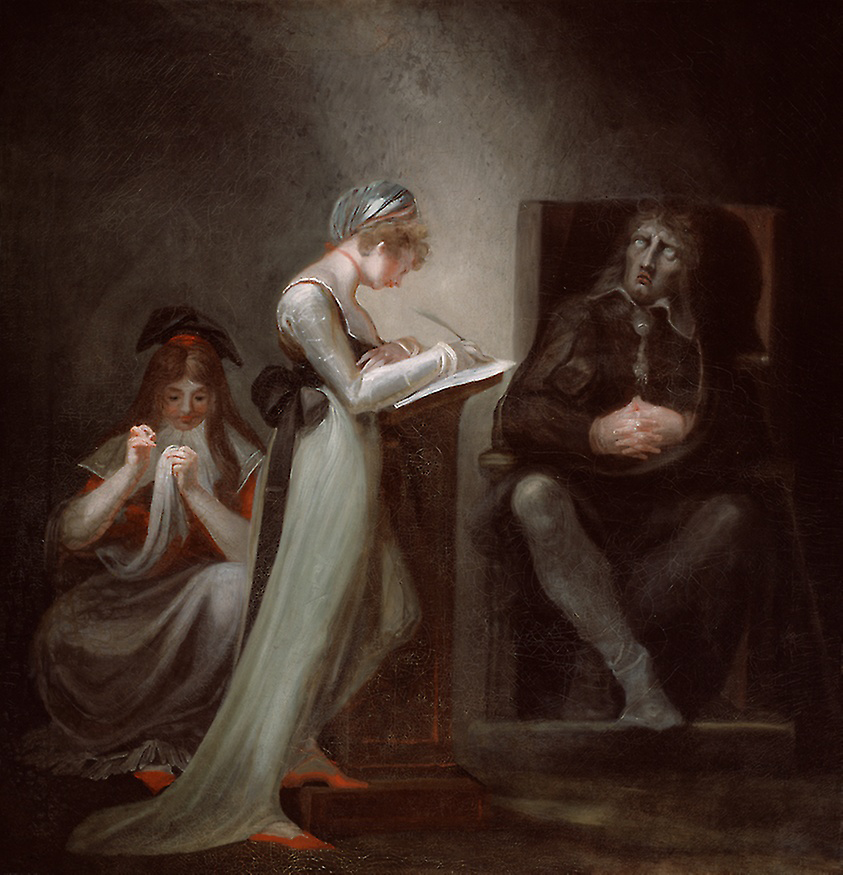

Like the traditional image we have of Homer, Milton is totally blind when he begins dictating Paradise Lost to his scribes, penniless, and in danger of arrest and execution for his radical republican views after the Restoration of 1660. But, he is very clear about his lofty ambition for this work. Certainly that is true of the poem’s blank verse form, but its thematic material is also quite a bit different from the usual epic stories of the exploits of kings, queens, knights, and pagan gods[v]. Paradise Lost is a biblical epic, partly about the fall of man from Paradise, but also about Satan’s motivations and machinations to bring about the fall. In Book I, where the reader meets Satan in Hell brooding over his lot, he convenes a meeting of all the demons who were cast out of Heaven – a pandemonium[vi] – where the best path to avenge their lot is debated, and a fateful decision is made.

The story of the battle for Heaven and the fall of man as told in the poem is a far cry from the treatment it receives in the Book of Genesis. Satan, for one, is a much more fully developed character, more like Iago in Othello or Tony Soprano than the one-dimensional embodiment of evil in Genesis and Christian theology; in fact, the Satan of Paradise Lost has often been construed as the model for the many anti-heroes that would appear centuries later in literature and popular entertainment, all driven by envy, lust for power, anger, and the desire for vengeance[vii]. As such, he is far more interesting than the “good guys” – Adam and Eve, God, the archangels Michael and Raphael, and the Son of God. The first four books of the poem in fact are primarily about Satan’s brooding, envy, and plotting.

The Son of God is the Father’s principal instrument in the defeat of Satan and his followers in the great battle for heavenly supremacy[viii]. This power struggle is brought vividly to life in Book VI, reading at times like the single-combat scenes of Homer’s Iliad[ix] (bloodless, however, because heavenly hosts don’t bleed or die), and at other times like battle scenes from the last two seasons of Game of Thrones. There is a decidedly non-Genesis plot twist in Book VI: beaten but not defeated after the first clash, Satan comes up with the idea of making and using cannons! In the final, climactic battle, the cannons are effective at first, but the good seraphim silence them by tearing up mountains and hurling them at Satan’s batteries. Even so, the battle advantage see-saws between the good host and the bad, until the Son of God rides in on an incredible chariot and saves the day single-handedly, literally pushing Satan and his host out of Heaven and down to Hell.

Satan’s tale is one of the two main story arcs in Paradise Lost; the other is the innocence, temptation, and ultimate banishment of Adam and Eve from Paradise. As approved by the Pandemonium early in the epic, it is Satan’s plan to strike at God through His most cherished creations, Adam and Eve, thus avenging his defeat and expulsion from Heaven. This is where the two story arcs intersect.

In Books VII and VIII, the archangel Raphael narrates the story of Creation to an inquisitive Adam, except for one aspect that he implies is above Adam’s pay grade: the nature of stars and heavenly bodies. This is interesting, because it seems to suggest yet another aspect of Milton’s intellectual curiosity. He visited Galileo in Italy in 1638 when the latter was under house arrest, and he even mentions the “Tuscan artist’s” (Galileo’s) Optic Glass in Book I, comparing the surface of Satan’s shield to the pitted, irregular surface of the moon as seen through the Italian astronomer’s telescope. Galileo is mentioned by name in Book V, the only one out of all Milton’s contemporaries to be named in the text. It would be decades after Milton’s death that Isaac Newton’s Principia Mathematica laid out the basis of our understanding of planetary motion, which Johannes Kepler had described empirically in 1619.

The actual, urgent reason for the conversation, however, is for Raphael to warn Adam of the danger lurking in Paradise, and of Adam’s duty of obedience to God’s commands.

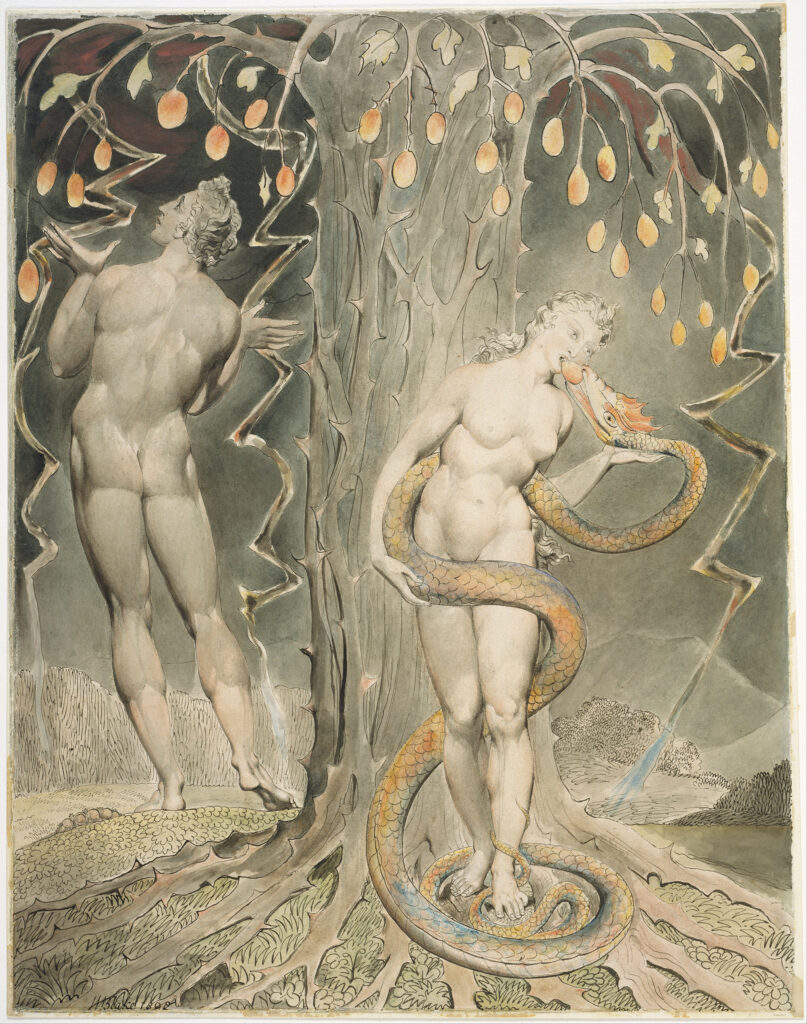

The climax of Paradise Lost occurs in Book IX, where Satan infiltrates Paradise as a mist, inhabits the body of a serpent, and persuades Eve to partake of the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge. The clever arguments he uses, and Eve’s own rationalizations for violating God’s command, are not much different than the arguments ordinary beings use every day to justify their bad decisions. Adam, resisting Eve’s blandishments to partake of the forbidden fruit, justifies his acquiescence by saying he would rather die with Eve (as God has told them they would) than obey His command and live without her. More interesting is what follows after he has eaten, and they’ve both given in to carnal lust and gone to sleep. When they awaken to the reality of what they’ve done, mutual recriminations follow, and the dialogue between them sounds like the kind of marital quarrel that circles around and around but goes nowhere[x]. The progenitors of humankind are now well on their way to becoming ordinary human beings. But, even couched in the archaic language and formal structure of the poem, the horror and despair that Adam and Eve experience when they understand what they have done is palpable. That horror and despair grow more intense in Book X, and one can’t help but share Milton’s empathy for this benighted couple.

Through the intercession of the Son of God, Adam and Eve are sentenced to expulsion from Paradise and avoid the death penalty, perhaps the first example of a plea bargain in high literary form. Through Books XI and XII, the archangel Michael gives Adam a preview of the principal events of several books of the Old Testament – Exodus, Judges, and Kings, among them – and foretells the birth, crucifixion, and resurrection of Jesus, as well as the redemption of mankind who put their faith in Him. Both arrive at an acceptance of their fate, and when Michael leads them out of the east gate of Paradise, they are calm and reflective.

Paradise Lost is a sprawling, marvelous epic that was far easier to read than I imagined, despite the constraints imposed by its iambic pentameter and archaic language. The mash-up of so many biblical and classical references require some consultation of other sources, and the first source I’ve listed at the end of this post will serve very well in that respect. The experience of reading the epic, however, is well worth the challenge. Paradise Lost works as pure poetry, as an audacious display of Milton’s mastery of classical and biblical themes, and as a meditation on Christian morality; only Ezra Pound in the 20th century pushed the boundaries of poetic material further, and he is much more difficult to read. There is so much going on in Paradise Lost that I know I will have to re-read the epic several times to grasp all the nuances. I recommend it without reservation to anyone with the patience and resolve to navigate through it. But this post is not about me; let’s return to the Broadkill 18.

Were these men, living in a backwater village several days’ difficult travel to an urban center, educated enough to have been exposed to Paradise Lost, and were any of them affluent enough to own any books aside from a Bible? Books in the colonial era were expensive, due to the fact that they were mostly printed in London and had to be shipped across the Atlantic. A few wealthy Americans possessed substantial libraries numbering in the thousands of volumes, and lending libraries were established in Philadelphia, Boston, and other urban centers, most on a paid subscription basis. Universities, of course, had their own libraries. For the majority of the population, libraries of any kind were geographically and financially out of reach. Much of what was available to read in the colonial era consisted of pamphlets and newspapers, which were easy to print locally and distribute.

After independence, literacy rates, especially among women, began to rise rapidly, and novels written in the new republic began to gain wide readership. These novels were preoccupied with providing moral guidance and cautionary tales to Americans; questions of freedom and responsibility were paramount in the emerging American literature. The growing readership for novels was not the same readership for epic poetry; I would submit that the readership for the latter was scant.

An education comparable to John Milton’s would have been available only to the sons of the affluent, bound for Harvard, Yale, and King’s College (now Columbia University). If the Broadkill 18 were literate, and most of them probably were, their reading was not likely to have been broad, in part due to the scarcity of printed books in the lower part of Delaware and also to their social class. In my opinion – and I must stress that it is an opinion, in the absence of detailed biographies of these men – it is unlikely that any of the Broadkill 18 had had the benefit of a rigorous education. The few that I’ve been able to find details on were merchants or tradesmen. It is hard to imagine someone with utilitarian literacy – enough with which to conduct trade, do sums, and write a contract – would have had the wherewithal to acquire, read, understand, and appreciate the complexities of Paradise Lost.

So yes, Areopagitica and Paradise Lost spoke to me in a big way, and no, I don’t believe that the town of Milton was consciously named for the poet. More than likely, the name is a contraction of Mill Town, as some have suggested (we have Milford, Millville, and Millsboro as other examples). As far as I can tell, no town anywhere in the state was named for a poet. However, I have no objection to honoring John Milton’s brilliance through a namesake town at the head of the Broadkill, intentional or not.

Finally, a plea: reading John Milton’s work would be a much better tribute to his brilliance than dressing him up as an Easter bunny.

Sources

The version of Paradise Lost I used for my reading was published in 2017 by Arcturus Holdings, Ltd., London, UK, and is on the shelves of the Rehoboth Public Library. It is not abridged or altered except for modernization of the spelling, which can make it easier for some readers to concentrate on the text. It also contains beautiful reproductions of the poet William Blake’s twelve illustrations for Paradise Lost, created between 1807 and 1820, which are remarkable and worth seeking out.

I recommend this site because it contains the full text of Paradise Lost in the original language (17th century spelling) with notes hyperlinked within the text: https://milton.host.dartmouth.edu/reading_room/pl/book_1/text.shtml

Full text of Areopagitica in pdf format:

https://resources.saylor.org/wwwresources/archived/site/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/ENGL402-Milton-Aeropagitica.pdf

Discussion of Areopagitica (much better than other sites, which are just crib notes for bleary-eyed college students)

https://aeon.co/essays/reading-john-miltons-areopagitica-in-the-information-age

Discussion of the development of the American novel in popular culture in the late 18th century:

https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_understanding-media-and-culture-an-introduction-to-mass-communication/s06-02-books-and-the-development-of-u.html

For the text and signatories of the petition to the state legislature to rename “Head of the Broadkiln” to “Milton”:

Harold Hancock and Russell McCabe, Milton’s First Century: 1807 – 1907

Cape Gazette mention of John Milton’s statue on Governor’s Walk:

https://www.capegazette.com/article/tourist-home-milton/152818

[i] Samuel Wright (tanner and merchant), Eli Hall, William Robbins, Cornelius Coulter (1781 – 1856, merchant), Thomas Fisher, Henry Little, David Conwell, Cary Stephenson, Dennis Morris, B. Benson, David Starr, Stephen Costen, Samuel Paynter (carpenter), Ebenezar Fredman, James Martin, Cornelius Cary (1780 – 1807), Joseph Cary (1770 – 1834), Shepard Conwell

[ii] Parliament allowed the Licensing Order of 1643 to lapse in 1695.

[iii] Written in the 1380s, Troilus and Criseyde (more familiar to us as Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida), is considered superior to the same author’s Canterbury Tales, but has received far less attention in the modern era

[iv] I’ve used modern English spelling in the passages I’ve excerpted from Paradise Lost, although many editions still use the non-standard spelling of Milton’s era.

[v] If the reader hasn’t figured this out, Milton makes it clear in the beginning of Book IX that he is not a student of knights, emblazoned shields, medieval warfare, jousts and tournaments, and is left to select a “higher argument.”

[vi] This is one of the thousands of new words Milton coined in English, often from Greek or Latin origin.

[vii] Satan’s catchphrase, which appears in Book I, is “Better to reign in Hell than to serve in Heaven”

[viii] Some critics have accused Milton of heresy, specifically Arianism, in depicting the Son of God as separate and subordinate to God the Father.

[ix] Satan faces the Archangel Michael in single combat:

…but the sword

Of Michael – from the armoury of God –

Was given tempered so, that neither keen

Nor solid might resist that edge. It met

The sword of Satan, with steep force to smite

Descending, and in half cut sheer, nor stayed,

But with swift wheel reverse, deep entering, shared

All his right side. Then Satan first knew pain,

And writhed him to and fro convolved, so sore

The griding sword with discontinuous wound

Passed through him…

[x] Milton, who was married three times, would have been well acquainted with this fruitless sort of arguing.

A mystery that will probably always remain a mystery. However to be proposed by these men that long ago in my mind doesn’t make much sense. Especially given the times. Thank you for that presentation of story line that could be. A lot of work on your part. I grew up here and appreciate all your efforts.

I’m glad you took the time to read the post – thank you. I’m finding myself less concerned about whether the town was named for a poet than I am about our fellow citizens knowing who John Milton was and appreciating his work. I had a ball researching and writing this post, and of course reading Paradise Lost and Areopagitica.

Phil:

I fully agree with you concerning the origin of naming Milton. In my childhood, during the 50’s there was no mention of John Milton the Poet. The older folks at that time used to sit around in the evening chating. I used to join my Father, sitting on the front porch of Granddad’s home at the conner of Federal and Poplar. I would enjoy listening and absorbing the gossip of the day. Never did I hear any mention of John Milton. This town was settled because of the Broadkill River and the daming of the creek which creating several mills. The surronding area also had several small mills. Thus, “The Town of Mills”.

Thanks as always for your interest, Fred. I would love to find out exactly when this tale actually entered the town conversation, because there sure isn’t anything in the newspapers or other documents about it. Your granddad and grandma and all the assorted aunts and uncles would surely have brought it up.

I concur with your conclusion that the town’s name, Milton was probably derived from Mill Town shortened to Milton. Being an industrial town centered around shipbuilding, farming, milling, and other blue collar type occupations it’s hard to imagine a literary society of men petitioning the government to change the name of the town to honor a classic poet.

Although the other possibility of the town being named after such a great and courageous man as John Milton isn’t objectionable to me.

I’d like to hear the story sometime as to how the bronze statue ended up in the park.

Thanks for your feedback – reactions are always appreciated! Regarding how the statue got commissioned and placed in the park, I’m looking into it and hope to have something to post on the subject in the near future.

I would just like to thank you for all of your hard work researching the John Milton saga in Milton. Real historians labor at a thankless task many times. Anyone who has done any research understands that a running history in Sussex County suggest that most of the towns in Sussex have a name related to the concept of various mills related to the agri- business community of the time. Milton was a back water farming town and the notion that it was named after the poet John Milton betrays our heritage and history of the hard working farm community that we represent. We should be proud of who we are as Miltonions and not of some lofty notion of silly superiority. I am proud to represent the real history of Milton. Thank you so much for putting the record straight.

Thanks for your interest – it’s always appreciated. I need a team of myth-busters to track down the origin of the John Milton hype (I’m getting close myself). I just wish that we could do better by John Milton in honoring him (start by reading his work, and forget about playing dress-up), even if the town wasn’t named for him. Understanding the true nature of life in early Milton and the people who lived here would be a reality check too.

I, too, have questioned whether Milton was named after John Milton. But after reading your blog, I dug out my copy of the Milton book I inherited from my grandmother! She was born in 1890 in rural Indiana. She went to college at Marion Normal College and got a degree in education. Her Milton book is signed inside with her name and address as Marion, IND. I assume Milton was part of her study.

She became a teacher in a one room school in Indiana. She loved to read and continued to educate herself. Could there have been a few….like her….who read Milton? I kind of doubt it but I thought this information might be of interest to you.

Thanks for your blog!!

First, thank you for your interest in the blog post and for sharing your grandmother’s story. I believe that a few generations ago, poetry and the humanities in general were a very important part of a broad liberal arts education, and John Milton was one of those in the Western canon that was taught and read widely. We can’t be sure if your grandmother read Milton as part of the curriculum in a normal school (specialized teachers college), which I believe was a two-year program, or whether she just did it on her own; either way, I know her mind was expanded in the process.