Two generations of the Davidson family of Milton had shipbuilding in their DNA.

Cranking out ships

Between 1875 and 1894, Cornelius Coulter Davidson (1827 – 1917), who went by the initials “C. C.”, built a total of 14 vessels, including an unusually long sail-steam hybrid, the Martha E. McCabe, and his largest, the Florence Creadick, both around 1889. He was sixty-six years old when he launched his final project, the Lydia and Mary. Cousin James Polk Davidson (1844 – 1915) built three from 1891 to 1904; the last of these was the ill-fated Marie Thomas, which assisted with putting out the devastating Milton fire of 1909 and itself burned to the waterline a few years later while docked on the Broadkill. Cornelius’s brother Andrew J. Davidson (1832 – 1880) built one in 1873. In the roughly thirty years that the Davidsons were engaged in shipbuilding in the Milton yards, the industry went from the tail end of the boom years to a complete bust.

James Polk Davidson’s son Andrew J. Davidson (1871 – 1945), not to be confused with C. C.’s brother of the same name, may have already seen the writing on the wall regarding shipbuilding in Milton by the time he was a young adult. He would choose a career path that would lead him out of Milton for the greater portion of his work life.[i]

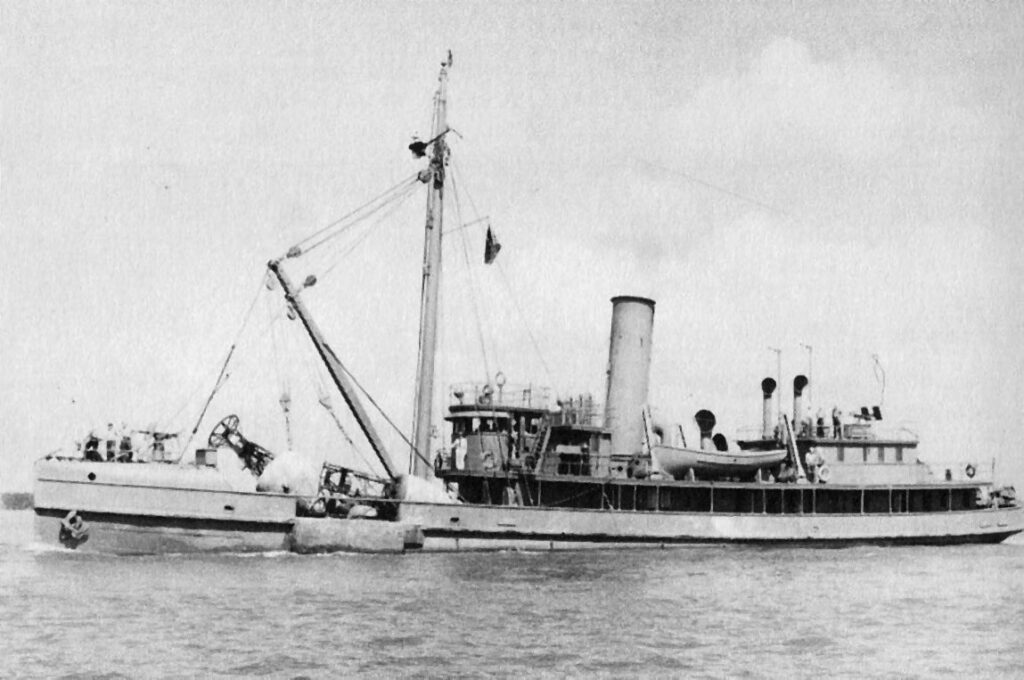

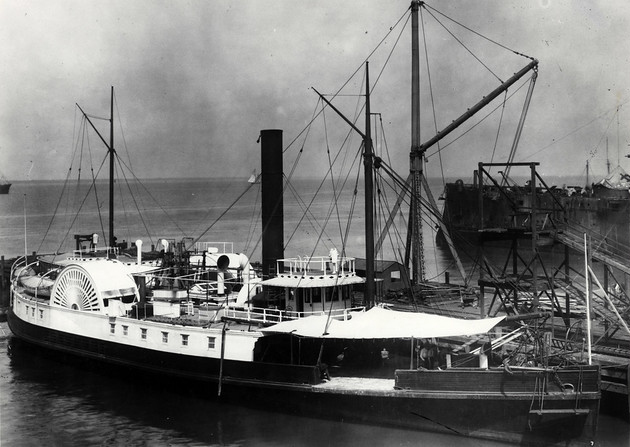

In 1890 he began work for the Lighthouse Service of the U. S. Department of Commerce, as a ship carpenter aboard the lighthouse tender Zizania[ii], named after a variety of North American wild rice. This was a fairly new ship, having been built in the Baltimore shipyards in 1888; it would be drafted into naval service in both World Wars I and II, finally being decommissioned in 1946. Andrew would see a lengthy term of service on the Zizania in the ports of New York and Boston. He received his 2nd Mate license in 1892, and was finally promoted to that rank in 1900.

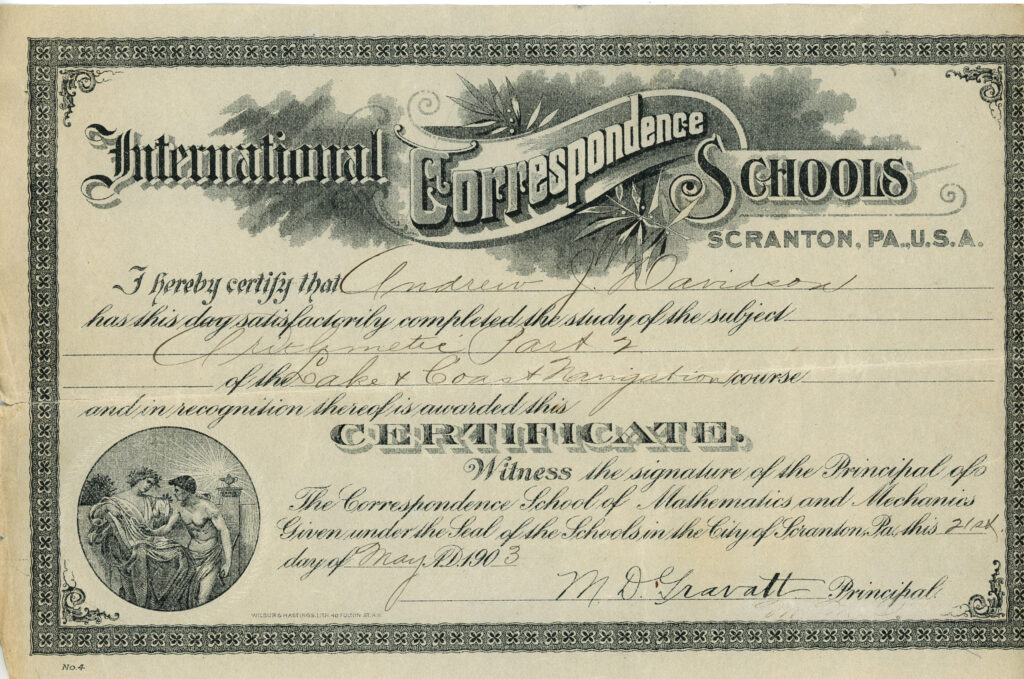

Davidson resigned from the Lighthouse Service in 1903. Perhaps it was the slow pace of advancement in the Lighthouse Service; it took eight years to get his promotion to 2nd Mate. It may have been the fact that in 1899 he married Sallie Holland Wilson, and they became the parents of daughter Grace in 1902. The couple were living at her parents’ home in Milton as of the 1900 Census, so there may have been an issue of making ends meet, or having someone to look after Sallie while he was out at sea. It is not hard, then, to imagine that he saw a pressing need to better provide for his family. Family documents show that between 1902 and 1903 he was he was taking correspondence courses[iii] in lake and coastal navigation, most probably not as a job requirement but to advance himself professionally.

His next move was to the Philadelphia Naval Yard, where he was employed as Shipwright 1st Class. He didn’t last long there, resigning his position in 1904.

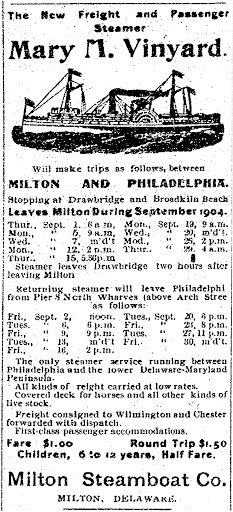

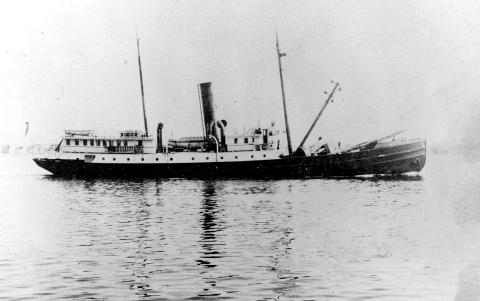

Master and Commander – of the Milton Steamer

Opportunity beckoned him back to Milton, or at least to the Milton steamer, the Mary M. Vinyard. When the service was inaugurated in 1904, he was offered the captain’s job, which surely sounded very good on paper. The service from Milton and Frederica to Philadelphia was received enthusiastically by the residents of Milton. Enthusiasm did not translate to profitability, however; facing stiff competition from the Queen Ann Railroad Company and other lines for both passengers and freight, the steamer lost money. It was sold by marshal’s auction in Wilmington to a Norfolk company in November of 1905, ending its run after less than two years. If Andrew J. Davidson had dreams of a rapid rise to “master and commander” (and the salary that went with it), the demise of the Mary M. Vinyard service put an end to them.

We don’t know what Andrew and his family did in 1906 and 1907; their second daughter Lydia was born in Milton in 1904, so they would have likely still been living with his father-in-law James Wilson. There was carpentry work to be had in town, and Andrew was an experienced hand, so there would have been plenty of ways for him to earn a living. One more child, Helen, was born in Milton in 1908.

Rejoining the Lighthouse Service

Fate intervened, however, in the form of a job offer as 1st Mate of his former ship, the Zizania. A letter dated December 23, 1907 states, in effect, that the position was his if he wanted it and offered a salary of $80 per month. This is roughly equivalent to $2300 per month in today’s dollars, a blue collar job that had to be performed under sometimes difficult or dangerous conditions. Then, as now, every dollar would have had to be stretched as far as possible on a salary that supported a growing family.

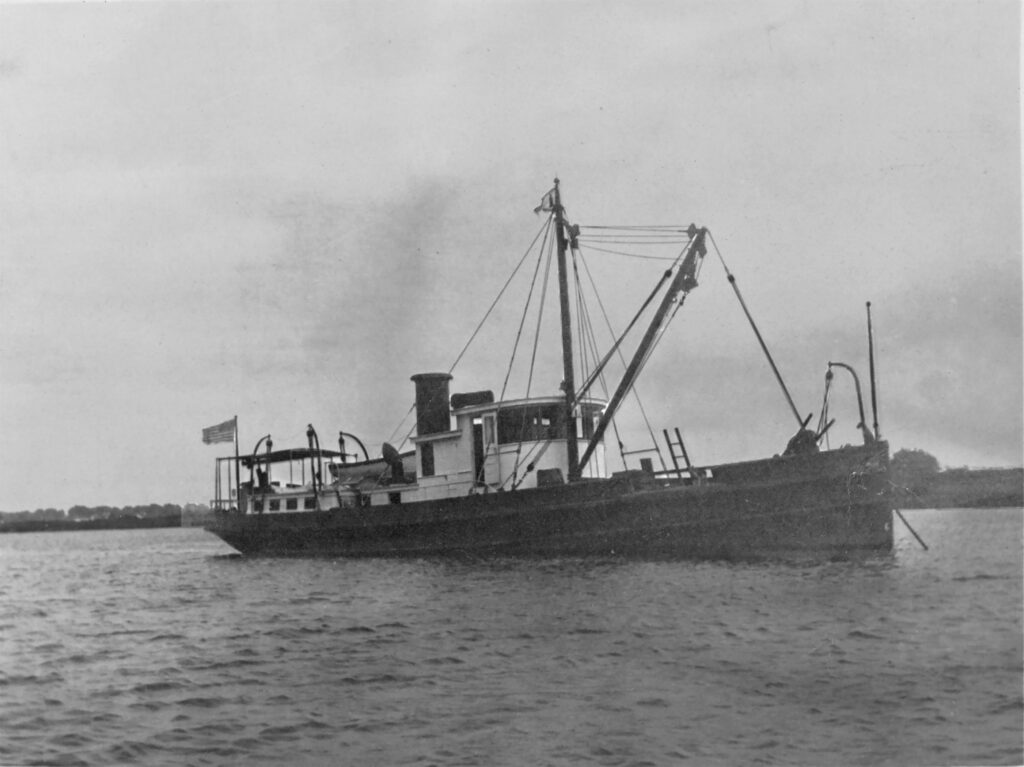

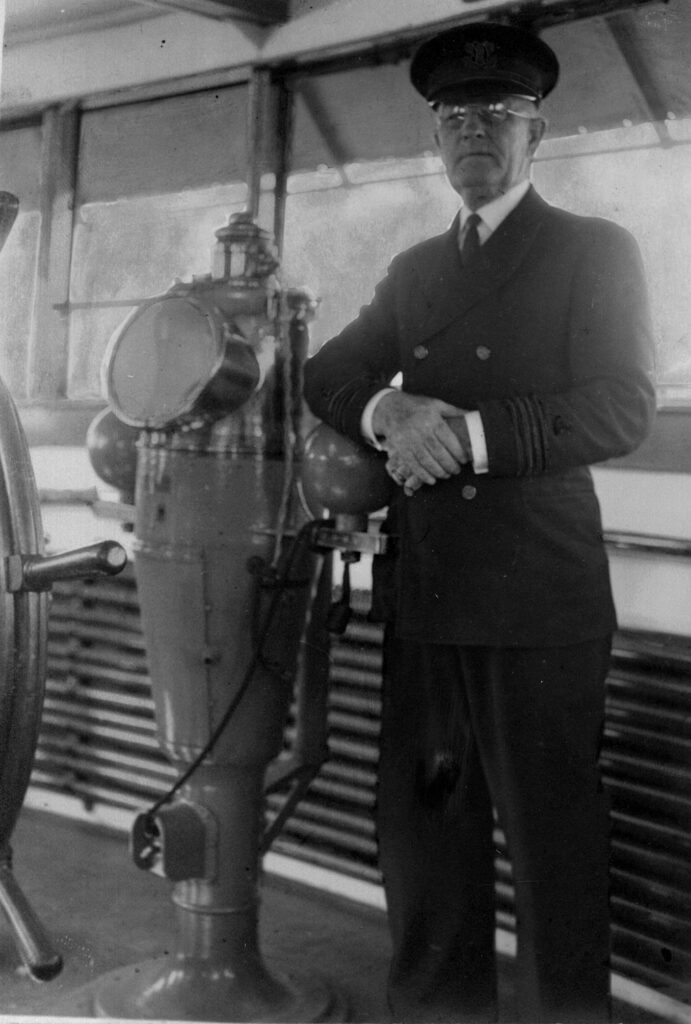

By 1911, the family had sufficient means to move to Wilmington; this is based on Sallie Davidson’s 1942 obituary, which states that she had been living in Wilmington for 31 years. The 1920 Census indicates that the family owned their home. In contrast to his experiences in his first job on the Zizania, 1st Mate Davidson was on what we would today call a fast track. From 1911 to 1912 he served temporarily on three different lighthouse tenders: the Anemone, the Larkspur, and the Iris. This is speculative, but often someone who is on the fast track will receive short rotating assignments to broaden his or her experience, in this case with exposure to different crews. In 1913, Andrew J. Davidson was promoted to Captain and assigned to command of the tender Woodbine; this outcome is consistent with the theory that he was fast tracked for advancement (or the 1913 equivalent of that term). Again, this is speculative on my part. His annual salary was about $1500, raised to $1520 in 1919. Their youngest, Andrew Alfred, was born in Wilmington in 1916.

Captain Davidson would remain in command of the Woodbine until 1928, but that doesn’t mean that his duties were routine throughout that period. During World War I, the ships of the Lighthouse Service, the Woodbine included, were incorporated into the U. S. Navy and used for defense-related tasks. For the Woodbine, these duties included patrols in the Delaware River and Bay, and deployment of submarine nets around Reedy Island[iv].

In 1928, Captain Davidson took command of a new lighthouse tender, the Wisteria, and was assigned a wide service area that included the Delaware River and Bay, Atlantic City, and the Atlantic Ocean down to Fenwick Island. The Wisteria, its crew and captain were transferred to the Baltimore and Norfolk Lighthouse District in 1930.

Career Capstone – the Lilac

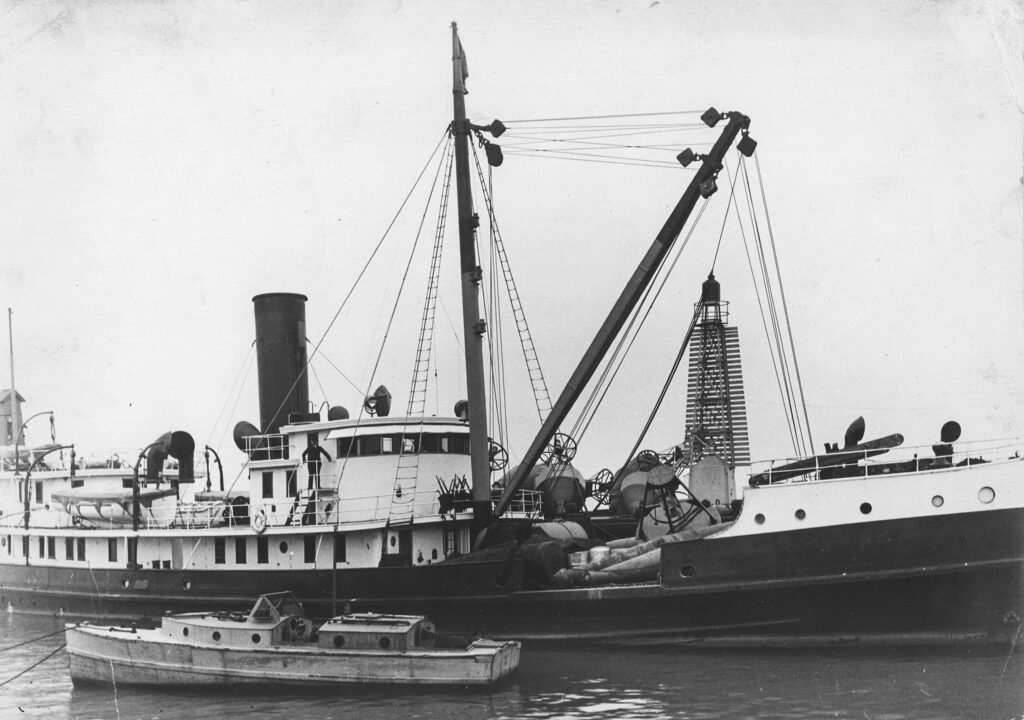

In 1932, Captain Davidson received his last command assignment: the new lighthouse tender Lilac, while the vessel was under construction.

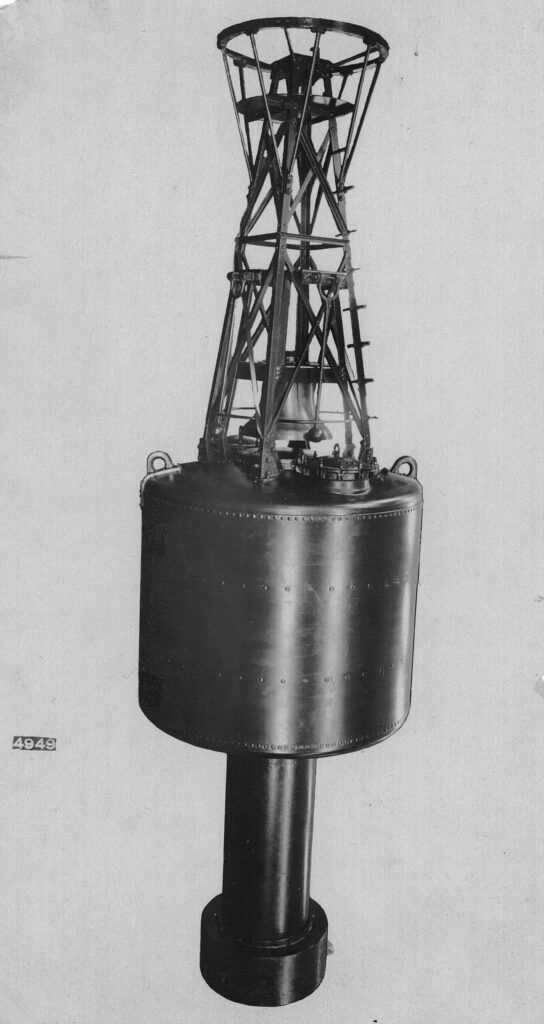

The Lilac was a steel hulled vessel built for the Lighthouse Service by the Pusey and Jones shipyard in Wilmington, DE. The keel was laid on August 16, 1932, and the launching took place on May 26, 1933. She had a steam powered piston-driven engine and a steam-powered boom capable of lifting buoys weighing 14 tons or more out of the water. Andrew J. Davidson was her captain for 5 years, until his retirement in 1938 after forty years of service. The following year, the Lilac was subsumed by the U. S. Coast Guard, designated WAGL-227, and would continue in service for nearly forty years until her decommissioning in 1972. Captain Davidson’s association with the Lilac assured that he would not disappear into obscurity with his retirement.

An examination of Captain Davidson’s retirement papers reveals that he did not work the full year during each of his last three years of service. His retirement age was 67, not out of the ordinary for his era. His obituaries state that the cause of death in 1945 was a heart attack. There is no way of knowing, with the material at hand, whether Captain Davidson had a chronic heart condition that limited his ability to work. His wife Sallie also died of a heart condition, in 1942, and we can ask whether he had cut his work hours short for her sake.

We know a great deal more about the physical specifications of the Lilac than of the crew; there is little in the way of first-hand accounts of what Captain Davidson’s personality and demeanor were like. Stephen Jackson of Rehoboth Beach wrote to Davidson’s granddaughter in 2009 and described the Captain, whom he met as a child in 1934, as “kind and patient,” taking him aboard the Lilac at Edgemoor[v] for short trips on the Delaware Bay. Another letter dated 1973 from Joseph Hill of Tucson, who worked with Captain Davidson, described him as “efficient” and “well-liked by everyone.” The Captain was held in high regard by his superiors in the Lighthouse Service, as letters to him upon his retirement can attest. On May 23, 1937, a visiting journalist from a Wilmington newspaper wrote a feature about the Lilac that extolled the ship’s excellent maintenance, the bravery of the crew that risked losing their hands to frostbite maintaining buoys in winter weather, and the “grand old man of the sea,” Captain Davidson. The large visitor suite with private bath, office, dining room, silver coffee and tea sets, and a crystal punch bowl on the buffet, seemed to impress the journalist almost as much as everything else about the ship and its crew.

Second Life

The Lilac is unique; she was never scrapped, and is thus the only surviving steam-powered Coast Guard lighthouse tender.[vi] Shortly after her decommissioning, the government donated her to the Seafarers International Union as a stationary training vessel at a seamanship school on the Potomac River. After the union retired her in 1985, she was sold into private hands and berthed at a marina on the James River in Richmond. In 1999, she went on the block again. It was at this point that the threat of the scrapyard was as real as it would ever be. Fortunately, a New York–based nonprofit which had already been engaged in preserving the tugboat Pegasus began the Lilac Preservation Project. By the winter of 2003, the Lilac was towed north to Manhattan.

Now a floating museum, she is docked at Pier 25 in lower Manhattan. A preservation effort spanning decades assured that she would remain viable and could welcome visitors; the ship is also listed in the National Register of Historical Places.

Epilogue

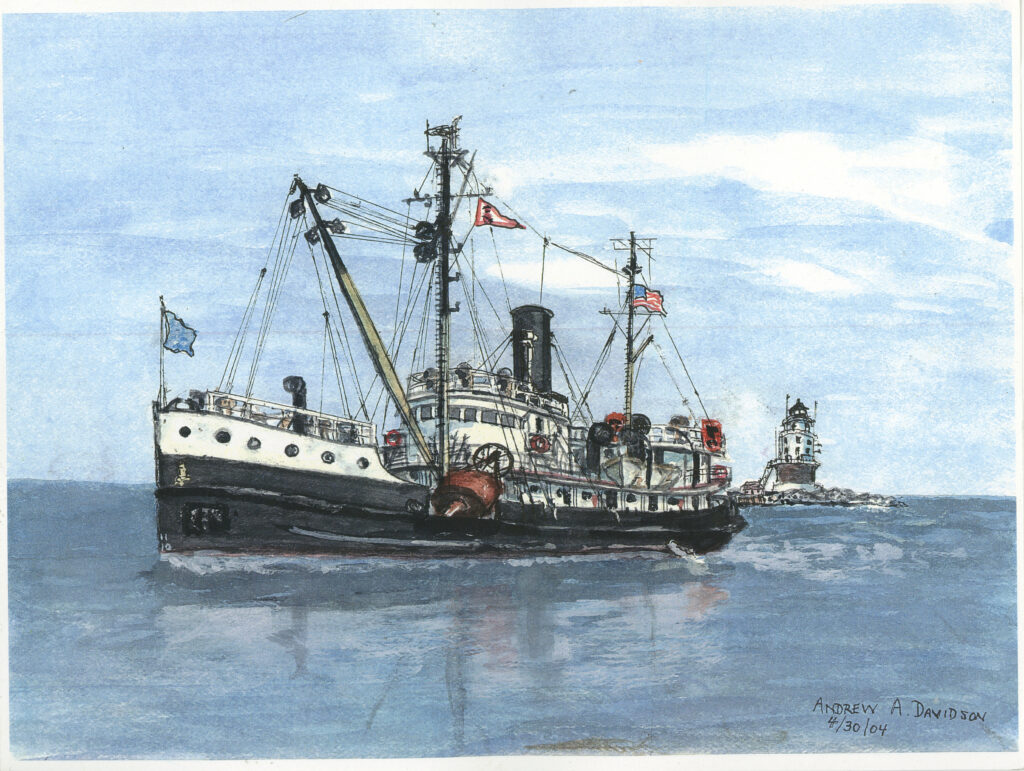

Captain Davidson’s only son Andrew A. Davidson (1916 – 2008) did not follow in his father’s footsteps, preferring a career on dry land while also pursuing his artistic passions. He spent plenty of time with his father aboard the Lilac; one of his renderings of the lighthouse tender can be seen below.

Sources

Davidson family archives, courtesy Sallie D. Macy

http://www.lilacpreservationproject.org/history-1

https://magazine.columbia.edu/article/tender

Wilmington Morning News, November 19, 1945, page 4

https://digitalservices.scranton.edu/digital/collection/ics/custom/history

Milford Chronicle, 1904 – 1905

Ancestry.com

[i] The outline of Andrew J. Davidson’s career was summarized in a two-page typewritten manuscript written by Grace Davidson Hearn, his oldest child, after his death in 1945. The document is undated, but would have had to have been written years prior to her death in 1978.

[ii] Lighthouse tenders in the 19th and twentieth centuries were traditionally named after plants and flowers.

[iii] The courses were given by the International Correspondence School of Scranton, PA. The school was founded in 1891 to teach colliery engineering and safety, but expanded greatly as it achieved commercial success. By 1996, demand for correspondence school curricula had decreased and the school changed its name and focus, but continues in existence.

[iv] Reedy Island is located near Port Penn, where the Delaware River narrows considerably. It did not have defense installations on it; it was primarily used as a quarantine station for ships headed to Philadelphia. Its location however, as a gateway to Philadelphia was highly strategic.

[v] Edgemoor is located northeast of Wilmington on the Delaware River, across the water from Penns Grove.

[vi] The Lilac had a sister ship built at the same time in the same shipyard – the Arbutus. After being decommissioned, she was acquired by the treasure hunter Mel Fisher who used her in the recovery of huge amounts of gold on the sunken Spanish galleon, the Atocha. When the treasure recovery was completed, the Arbutus was purposely sunk in the Florida Keys.

Thank you so much for this wonderful glimpse of Milton families and ship building history.

Enjoyed reading this.

I’m very pleased you enjoyed this story – I had fun putting it together, and learned a lot more about Milton in the process.

Outstanding Phil!!! I have shared with many people!History is important! Sallie

Thank you Sallie; pass it down to your children and grandchildren, so they can keep the Captain’s memory alive. Your enthusiasm was infectious and your willingness to help me with this project was invaluable. There’s no other way I could have done it. Next step is getting the material into the Milton Historical Society’s archives.