Some months ago, I posted the story of Captain Lacey’s Narrow Escape, an ordeal at sea in which the crew of the sloop Edward J. Berwind nearly lost their lives during a hurricane in the mid-Atlantic Ocean, in early February 1908. A four-masted schooner, the Edward J Berwind was built in Camden in 1894 and serviced the coastal trade from the Gulf of Mexico to Philadelphia and beyond.

Up until recently, I had no photograph of the Edward J. Berwind, whose master was Capt. Frank Lacey of Milton. Quite by accident, I found a photograph in the Milton Historical Society labeled Schooner “Edward Barimud” and its captain identified as “Frank Larke.” The photograph, large and in decaying condition, was purchased by a Milton resident at auction and donated to the museum in 2007 or earlier. I strongly believe that the photo is of the Edward J. Berwind and its captain, Frank Lacey, made around 1906.

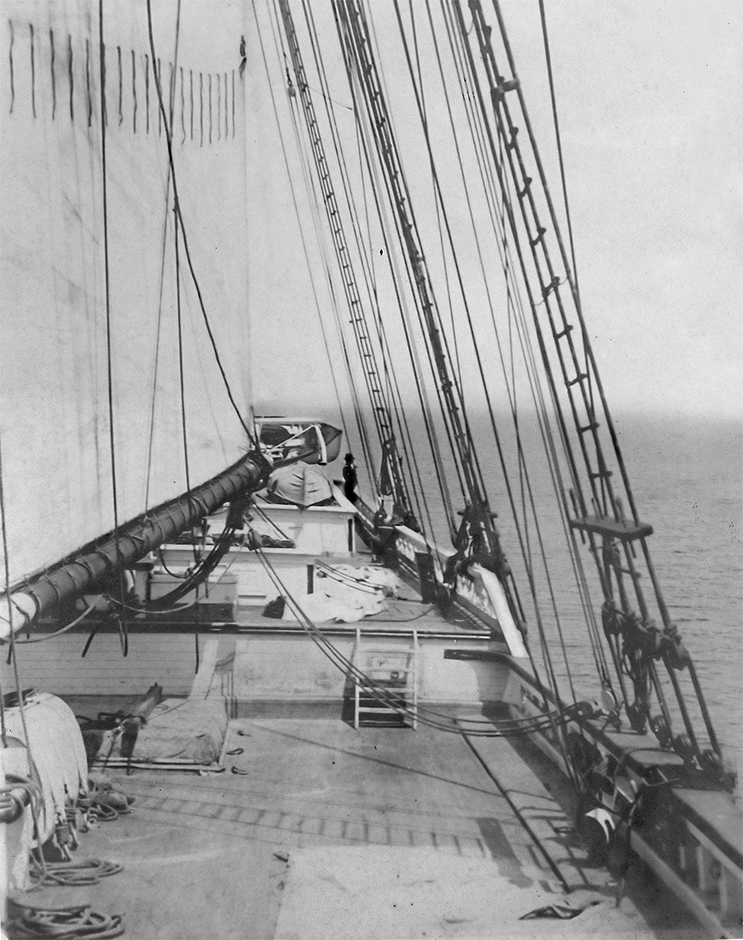

There are several factors that make this photograph unique among the other photos and paintings of schooners in the Milton Historical Society’s collection. First, the photograph was taken aboard the vessel instead of from a dock or a distant vantage point. Second, the ship appears to be in open water, under sail; a sail and boom are clearly visible at left. A photographer aboard a sailing ship, out in the open sea, is uncommon in the early twentieth century; it is the first I have run across.

Now imagine this ship caught in a hurricane off the Carolinas, battered by powerful winds and huge waves breaking over its deck, springing a leak and taking on water faster than the crew could pump it out. They struggled for five days and nights, but the ship was doomed. Fortunately, they were spotted by the British steamer Mercedes De Larrinaga, whose personnel were able to carry the Berwind’s exhausted crew to safety. They were taken to Liverpool and came back to the U. S. about February 24. The water-logged, abandoned vessel was later set on fire by another ship to destroy it and keep the hulk from becoming a menace to navigation.

Edward J. Berwind (1848 – 1936), the son of German immigrants and for whom the sloop was named, was the largest individual owner of coal mines in his day and very wealthy. A graduate of the U. S. Naval Academy, he served 6 years as an officer, from 1869 to 1875. Perhaps this early interest in the marine field led him to acquire interests in steamships and other vessels, or it just made business sense for him. A tugboat was named for him, as well as a Great Lakes freighter.

Hi Phil, great photo. It made me wonder how easily a person could travel to other countries without having papers or passing through check points in the middle to late 1800’s ? Would it have been easy to travel without leaving a trace ?

Passports as we know them today for European countries were not instituted until WWI. The U.S. followed suit, but I haven’t established exactly when. We had severely tightened our immigration laws in the 1920’s as well.

As for traveling “off the grid,” it was certainly more possible in the 19th century, but not easy. Most passenger ships kept lists of who they were transporting, and cargo ships of any size kept a crew roster.i don’t think the Edward J. Berimund kept a formal crew roster, at least not one I can locate.

That being said, it appears to me that with the use of a false name you could slip in and out of Europe without revealing your true identity. I haven’t looked into other continents yet, but with the exception of Japan until the mid19th century it was easy to get in and out of most places without leaving a trace.

Happy New Year to you and yours!

Thanks for your comments Phil.

A very Happy New Year to and yours too !

Dear Phil Martin,

I very much enjoyed reading your article. The story and the photograph are quite interesting.

I’m sure you’ve already heard this by now, but in case you haven’t, the terms schooner and sloop are not interchangeable. A sloop has only one mast where a schooner has at least two. Both are fore-and-aft rigs, meaning the sails set above a boom instead of hanging from a yard or gaff with no cloth ahead of the mast. The main mast is the second and tallest mast. The Edward J. Berwind is described as having four masts.

The photograph shows three sets of shrouds along the gunnells to support the ship’s masts. That would make the sail in view the mainsail with the mizzen and the spanker hidden behind it. The foremast is behind the photogragher. The hanging tassels lining the sail are called telltails to gauge air flow over the sail. This boat is clearly sitting becalmed on a nearly windless day, allowing a rare moment to set up a tripod plate camera to take an exposure long enough to produce such an excellent image. A picture like that would be very carefully staged, so I would conclude, as you have, that the man smoking his pipe is the ship’s master.

Again, thank you for the interesting article and posting of such a wonderful potogragh.

Sincerely, Will Gilmore

Thank you so much for this feedback, Will! I am definitely not familiar with the seemingly infinite varieties of sailing vessels, but you point out a pretty basic error on my part that no one else has. I am also really, really pleased with the insight you offered in the second paragraph: the tassels hanging straight down indicating that the ship was becalmed; I would never have known that, but this adds a great deal to the analysis of the composition of the photo. I thank you again!